[ad_1]

The retreat by the developed world’s big central banks from ultra-loose monetary policy is imposing a severe stress test on the global financial system. That much is clear from the lack of liquidity in markets — liquidity being the ability to buy and sell without causing big moves in prices.

Signs of financial instability have recurred since the seizure in the British gilt-edged market in late September which stemmed from pension funds’ so-called liability-driven investment strategies.

The Bank of England’s decisive move to act as a buyer of last resort succeeded in restoring order to the gilt market after the Truss government’s disastrous “mini” Budget on September 23.

But the episode provided early warning of what the future might hold as a result of radical changes in the structure of the financial system since the crisis of 2007-09. It seems questionable whether regulators are fully abreast of these seismic shifts. The gilt market debacle also raises wider questions about whether pension systems are fit for purpose.

Defined benefit pension schemes — employer-backed funds that promise retirement benefits related to pay and length of service — have traditionally been a stabilising force in the financial system. A classic case in point was the financial crisis of the mid-1970s when pension funds helped bail out the UK banking system by buying risky properties that were weighing on bank balance sheets. Because they were “immature”, meaning that their income from investments and pension contributions far exceeded their pension outgoings, their capacity to absorb risk and shoulder losses was considerable.

With the ageing of advanced country populations, maturity has arrived and pension funds have a much reduced buffer of safety. In the UK, most sponsoring companies have sought to limit their exposure to pension fund liabilities by closing their defined benefit funds to new members and establishing defined contribution funds, in which pensions vary with investment returns.

Part bank, part hedge fund

Under pressure from the Pensions Regulator, pension fund trustees are no longer primarily focused on maximising returns in defined benefit schemes. Instead, they concentrate on hedging against inflation and interest rate risk, while matching the future timing of pension outgoings as they fall due with bonds of appropriate maturities.

This is liability-driven investment, or LDI. The strategy, carried out for the pension funds by independent fund managers, has the notable advantage of reducing the volatility of pension fund assets and liabilities. But there is a snag, in the form of leverage, whereby pension funds borrow against the collateral in their gilt portfolios to establish the hedges.

Con Keating, of consultants Brighton Rock Group, and Iain Clacher, of Leeds University Business School, pointed out to the work and pensions committee of the House of Commons last month that, as a result of leveraged LDI, many pension funds had gone from being long-term savings institutions with an ability to withstand short-term market fluctuations, to institutions where “the immediate and short term are all important” and their ability to bear risk is “significantly impaired”.

In other words, these pension funds now resemble a cross between a hedge fund and a bank. They are vulnerable to the equivalent of bank runs when they face margin calls from their LDI managers.

Why did this happen? Essentially, the LDI build-up was a reaction to market developments after the financial crisis. Pension funds calculate the net present value of their liabilities using a discount rate related to gilt yields. Trustees then assess whether there are sufficient assets to meet future pension obligations and whether the level of contributions needs changing.

It is worth noting that the use of gilt yields is a much harsher discipline than using higher corporate bond yields, as company pension funds do in the US. Legislation in the US also allows liabilities to be discounted at a 25-year moving average. Such averaging prevents freakishly low post-crisis bond yields from causing the value of pension liabilities to balloon as they have done in the UK.

One part of the explanation for this contrasting approach to the valuation of pension liabilities is that the UK’s pensions regulator has a statutory obligation to protect the Pension Protection Fund, the official body that steps in to pay pensions when a sponsoring employer goes bust and the pension fund is in deficit. The regulator thus has an incentive to demand valuations that are as stringent as possible. Well-funded or over-funded schemes take the regulator off an uncomfortable hook.

To complete the story, when bond yields fell and the value of liabilities rose after the 2007-09 financial crisis, LDI portfolios were generating only threadbare income from which to pay pensions. The strategy was thus expensive, potentially requiring big increases in contributions from employers and scheme members.

Spiral of value destruction

Actuarial consultants responded to this problem by advising trustees to take on leverage by obtaining exposure to bonds through derivatives such as interest rate swaps and repurchase agreements, or repos. That way they could reduce the volatility of the fund’s assets and secure the inflation and interest rate hedges they needed.

The cash released through leverage could then be used to buy higher yielding assets such as equities, property and infrastructure. For funds with a deficit of assets against liabilities, investing in riskier assets held out the hope of closing the funding gap. Yet in the end the strategy boils down to one more example of the manic, high-risk search for yield that prevailed in markets in the period of ultra-low interest rates.

John Ralfe, an independent consultant who pioneered liability-matching strategies while he was head of corporate finance at the retailer Boots, is a vociferous opponent of leveraged LDI and argues that it amounts to pure speculation. Most of the swaps, repos and other derivative instruments used to facilitate leveraged LDI are, he says, opaque, complex and expensive. But, he claims, they are lucrative for the consulting arms of actuarial firms whose business models benefit from complexity to make a living. He also believes trustees and even some consultants did not understand what they were doing.

Certainly many trustees were wrongfooted when the LDI funds in which they invested came under severe pressure as long-dated gilt yields rose with unprecedented scale and speed in September, causing capital values to fall. This triggered calls for additional collateral from the pension funds, some of which either could not or would not stump up.

There followed what Clacher and Keating call a self-reinforcing death spiral of value destruction, exacerbated by banks’ reduced ability to deal in securities on their own account, which was a product in part of the regulatory capital requirements introduced after the financial crisis.

The damage was particularly acute in LDI pooled funds which are managed for mainly smaller pension funds. The speed and scale of the moves in gilt yields outpaced the ability of smaller pooled fund investors to provide new money when confronted with margin calls. Many had difficulty in processing the calls.

Sarah Breeden, executive director for financial stability at the BoE, observed in a recent speech that the self-reinforcing spiral meant that about £200bn of pooled LDI funds threatened the whole £1.4tn traded gilt market that acts as the foundation of the UK financial system, underlying around £2tn of lending to the real economy through the wider credit markets. This potential systemic threat to financial stability caused the central bank to step in with £19.3bn of temporary support. It was worried, among other things, about an excessive and sudden tightening of financial conditions for households and businesses.

Breeden’s verdict is that the root cause of this crisis was poorly managed leverage.

Other countries, most notably the US and the Netherlands, have large defined benefit pension systems that have not been wrongfooted by rising rates. The question is why. Sirio Aramonte and Phurichai Rungcharoenkitkul, writing in the Bank for International Settlements’ latest quarterly review, point out that US pension funds seldom use leverage, while Dutch funds hedge less than 60 per cent of their interest rate risks on average. The UK regulatory authorities appear to have adopted a much more relaxed attitude to leverage than their counterparts elsewhere.

In fairness to the regulators, the pension funds were victims of a liquidity crisis, not a solvency crisis. Data from the Pension Protection Fund show that, while the value of defined benefit pension assets fell by 20 per cent in the year to the end of September, the value of the liabilities fell by a much greater 36 per cent because of the impact of rising gilt yields on discount rates. This caused pension fund deficits to narrow or move into surplus. LDI advocates also point out that the strategy provided considerable protection in early 2020 when markets buckled under the stress of the pandemic.

That said, the market value of the pot from which pensions have to be paid is much smaller as a result of the market declines this year, while the fall in the net present value of the liabilities is based on assumptions that could turn out to be erroneous. So it is possible that the improvement in funding may prove less solid than it appears.

Collateral risks of reform

The regulatory authorities in Ireland and Luxembourg, where most LDI funds are domiciled, are urging funds to build resilience through bigger liquidity buffers against extreme market fluctuations. But that still leaves structural problems in the wider financial system, not least those that arise from the lack of diversity in the portfolios of defined benefit pensions schemes.

John Nugée, a former chief manager of the reserves at the BoE who now runs advisory firm Laburnum Consulting, says: “The problem with LDI is not that it makes any one pension fund safer or less safe, but that if everyone employs it, it makes the market overall less safe because when it moves, it all moves in the same direction.” He warns of a monoculture in which pension funds following official advice to employ LDI erode the market’s resilience to shocks.

Nugée adds that an approach that concentrates too hard on making one financial sector secure will often cause risk to migrate to other parts of the financial ecosystem. That was clearly true in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Regulators have succeeded in strengthening the banks but at the cost of reducing their willingness to take risk on to their own books, which reduces market liquidity as mentioned earlier. So risk has shifted to less-regulated and less-well-capitalised parts of the non-bank financial sector. That includes pension funds, which are very heavily regulated in the UK but not in relation to leverage.

Another post-crisis reform with unintended consequences was a more widespread collateralisation of derivatives, a move aimed at reducing counterparty risk. Breeden, of the BoE, argues that this has contributed to volatility while amplifying shocks in a falling market.

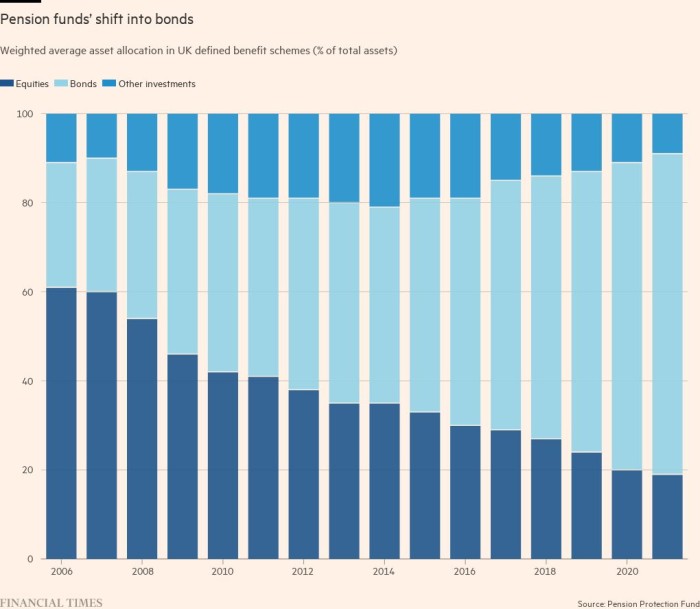

With defined benefit schemes shrinking as part of overall work-based pensions relative to defined contribution schemes, the LDI problem will wane over time. Yet an important legacy is a dramatic change in the capital market landscape, once again most notably in the UK. Since the early 2000s, UK pension funds have been consistent sellers of equities as they bought what now amounts to about a quarter of outstanding gilts. Their ownership of UK-quoted equities, meantime, has fallen from 21.7 per cent at the end of 1998 to just 1.8 per cent at the end of 2020.

Whether that matters, given the globalisation of capital flows, is moot. Foreign ownership has more than filled the gap, rising from 30.7 per cent to 56.3 per cent over the same period. And UK pension funds support the domestic corporate sector by other means via the credit, bond, infrastructure and private equity markets.

With retail price inflation in double figures, there is a real question as to whether work-based pensions can maintain pensioners’ living standards in real terms. In most UK defined benefit pension funds, inflation proofing is capped, often at 3 or 5 per cent.

Part of the logic of leveraged LDI is to build up the return-seeking part of pension fund portfolios from which the trustees can pay discretionary pension increases to address problems such as inflationary shocks. Yet in practice, trustees are often constrained where trust deeds stipulate that discretionary increases must be agreed by the employer.

Against the background of the pandemic, energy price increases, rising wage pressure and a squeeze on supply chains, few employers are in a mood to sanction generous discretionary increases. So many pensioners will be condemned to falling living standards this year and probably next year as well.

The position of members in defined contribution schemes is worse. More than 90 per cent are in arrangements whereby their investment pot switches from risky equities to supposedly safer bonds as they approach retirement. This so-called de-risking has in fact been highly risky for pre-retirement members. In what has been the greatest bond bubble in history, they have been put into exceptionally expensive government IOUs at negative real yields. Those bonds have collapsed in value this year in close correlation with equities, inflicting heavy losses on them.

All of which suggests that the provision of work-based pensions is seriously dysfunctional and in need of drastic rethinking.

[ad_2]

Source link