[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of Martin Sandbu’s Free Lunch newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Thursday

The impact of the energy crisis on European industry continues to be debated hotly. When I highlighted in last week’s Free Lunch how well the continent’s manufacturing has held up, the reactions varied from denial to surprised delight. As economics professor Daniela Gabor said in a tweet echoing my own sentiment, “I was very gloomy doomy about carbon shock therapy — and so far, quite wrong. Nice one.”

That is not, of course, how many European leaders see it. High energy prices are instead seen as an existential threat to the industrial base, which, to top it off, is being lured away — so the argument goes — by unfair US green subsidies. (“We wanted you to take climate change seriously but not so much that your companies produce green technology in competition with us,” seems to be the view of some.) Cue a string of promises, from reassurances that Washington will tweak its policies so as to leave Europe’s industry unharmed, to a commitment to greater subsidies back at home.

Since the debate rages on, it can’t hurt to take another dive into the data and what they should mean for policy.

Start with Europe’s impressive ability to adapt to higher natural gas prices. My colleague Shotaro Tani added to the evidence of this, reporting on Monday that European users cut consumption by one-quarter in both October and November, relative to five-year averages. This was largely accounted for by cuts in industry demand for gas.

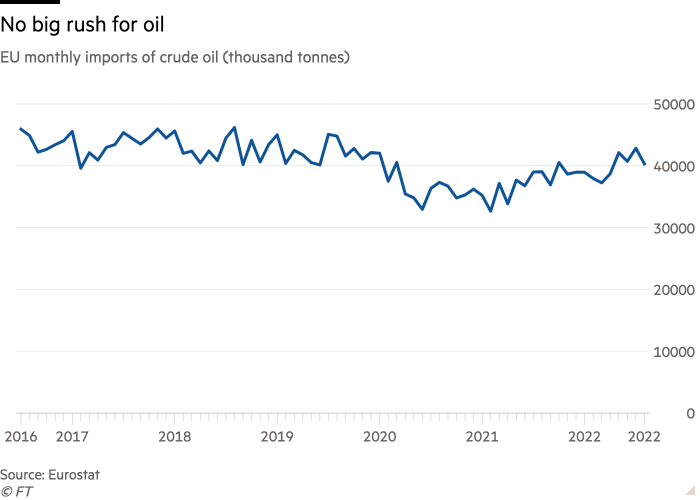

Some reactions to my celebration of this success have come from a climate change angle. They argue that gas reductions have only been achieved at the cost of consuming more oil, or of substituting coal for gas in power generation. So I went to have a look at the data, and I can reassure the sceptics. The chart below shows the EU’s oil imports, which look pretty flat over this year and are, if anything, below pre-pandemic levels.

And while there have been reports of coal use increasing, the numbers are clearly not enough to move the needle at an economy-wide scale. Here is a chart of coal consumption in EU electricity generation; again it remains below pre-pandemic levels.

Others resist the interpretation that Europe’s industry has weathered the crisis well, as I argued last week. And there are certainly reports of some production shutting down. [German chemicals group BASF is a case in point.] But this has to be seen against the background of overall growth in factory output in almost every European country, as I documented last week.

For more detail, take the latest industry numbers from Germany. “Industry excluding energy and construction” — that is largely manufacturing — produced 0.8 per cent more in October than one year earlier. Within this, “energy-intensive branches” recorded a fall of 12.6 per cent over the year (these are five sectors that account for one-fifth of value added in industry but three-quarters of its energy use). So manufacturing that uses a lot of energy contracted sharply, other manufacturing grew, combined growth was positive — it all looks just how we want an adaptable capitalist market economy to behave.

Finally, some object to comparing factory output today with a year ago, given how the pandemic turned our economies topsy-turvy. Fair enough. But taking the long view surely means focusing on the fact I highlighted last week, that the EU’s manufacturing output is greater than ever. If this is a crisis, it’s not a bad one to have.

Admittedly, it is a counterintuitive situation. So it is natural to be disorientated by the better-than-you-think story told by the statistics (certainly I was, as I expected things to be worse). But it is not healthy for the public debate to be confused by ideas about what (as I channelled Mark Twain in another context) we know for sure that just ain’t so.

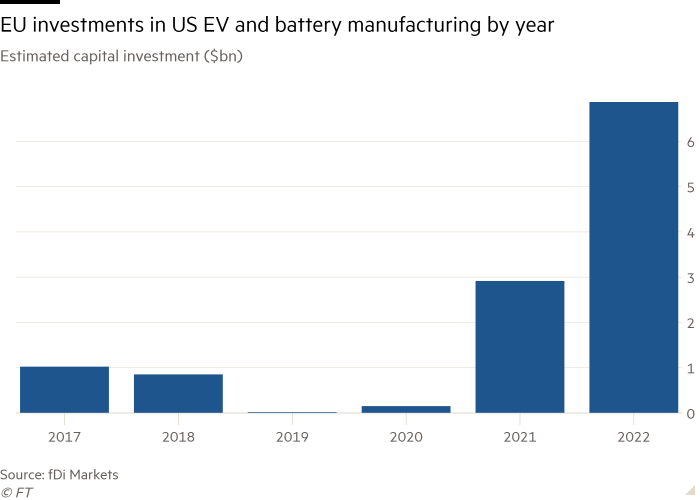

Take the widespread worry (eminently described by my colleagues over at the Energy Source newsletter, whose chart I reproduce below) that the US is stealing Europe’s bacon, or at least its investments into batteries and other technologies of the future.

But there seems to be similar angst about Chinese companies building lots of battery factories in Europe. Can you really be complaining about both things at the same time? Maybe this is simply a story about business leaders building batteries wherever there will be demand for them — which now includes the US, and has clearly not stopped including Europe. The more the merrier.

Of course, one can believe that for “strategic autonomy” reasons it is better for European battery demand to be met by European-owned or European-controlled battery production situated in Europe. But if that is the case, it is a bit rich to complain about the US trying to achieve precisely that with the clumsily discriminatory tax credits European leaders are so up in arms about.

What would be a more clear-headed way of thinking about Europe’s green industrial future? I had a stab at it in my column on Monday, where I argued that the EU should draw the consequence of being a fossil energy-poor continent: namely not to try to maintain a fossil energy-intensive industry. Instead focus both on accelerating the green transition, massively expand renewable power generation and transmission, and cultivate an industry that can thrive in a renewable energy system. That could mean pursuing production methods that are adaptable to the volatility of renewable power — from aligning production phases with different energy needs with power price fluctuations to incorporating thermal and energy storage in factory facilities.

I was pleased to read a punchy op-ed in our pages by Fatih Birol, head of the International Energy Agency, arguing along similar lines: Europe must face up to structurally higher fossil fuel prices but it has an opportunity to build an industry geared to a decarbonised economy. But that requires “a master plan for the future that goes beyond survival mode”.

And finally, read the sharp analysis by Georg Riekeles and Philipp Lausberg of the European Policy Centre. They call for a new trillion-euro EU financing mechanism based on common borrowing. One can quibble with the details. But that’s the scale of ambition that is required.

Other readables

-

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is the FT’s Person of the Year. Our editor went to interview him.

-

This week the EU started its Russian oil import embargo, and the bloc and the G7 introduced their price cap on Russian oil sold anywhere in the world with their companies’ help. The EU’s announcement is here and the US Treasury’s fact sheet here.

-

The cost of living crisis is driving more women into sex work.

-

The EU-Western Balkans summit took place in Tirana this week. In a new report, the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies shows that it is high time for the EU to start taking the region seriously and speed up its integration with the bloc.

-

The Bank for International Settlements warns that market crashes could complicate the tightening of monetary policy.

Numbers news

-

The share of multinational corporations’ profits squirrelled away to tax havens did not fall after policymakers began to address the issue after 2015, new research finds. Since global profits continued to rise, so did the associated tax loss.

-

Britons’ healthy life expectancy is worsening, writes Sarah O’Connor.

FT survey: How do we build back better for women in the workplace?

We want to hear about your experiences – good and bad – at work both during the pandemic and now, and what you think employers should be doing to build back better for women in the workplace. Tell us via a short survey.

Recommended newsletters for you

The Lex Newsletter — Catch up with a letter from Lex’s centres around the world each Wednesday, and a review of the week’s best commentary every Friday. Sign up here

Unhedged — Robert Armstrong dissects the most important market trends and discusses how Wall Street’s best minds respond to them. Sign up here

[ad_2]

Source link