[ad_1]

When the head of the UK’s Debt Management Office mentions “a very large amount of money”, people pay attention. So reporters duly did in March, when the normally publicity-shy Robert Stheeman used those words to describe Britain’s looming borrowing requirements.

He said that the DMO would issue £241bn worth of gilts in the coming financial year — a sum second only to the near-half a trillion pounds’ worth issued at the height of the pandemic. But, today, tighter financial conditions, higher interest rates, and an approaching recession make the task more complicated.

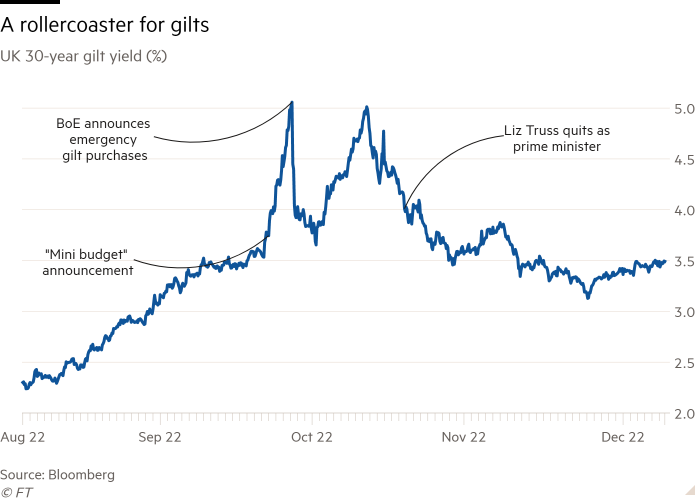

It might have been harder still, given borrowing conditions at the end of last year. An ill-fated spending plan from the government of Liz Truss was badly received by the market and evoked comparisons with the policies of debt-laden Italy. Spreads on gilts — the premium return they had to offer investors, compared with benchmark bonds in Germany — soared and a major financial crisis in pension funds was only narrowly avoided. Now, though, with a new UK prime minister and chancellor taking a more conservative approach, that so-called “idiot premium” on British debt has subsided.

“[Prime minister Rishi] Sunak and [chancellor Jeremy] Hunt are running a much steadier ship, one that is much more favourable for gilt markets with significant tightening over the forecast period,” says Paul Dales, UK economist at Capital Economics. Inflation and the expected path of interest rates have again become the primary forces driving borrowing costs, he notes.

Dales also thinks the Bank of England is on top of the problems caused by the Liability Driven Investment strategies used by pension funds. These are designed to protect Britain’s defined benefit, or “final salary”, pension schemes from falling interest rates, by hedging against them using derivatives. When the Truss plan sent gilt yields rising, however, these hedges backfired and sparked margin calls on the overexposed funds. Pension funds were forced to dump gilts to meet the calls, creating a feedback loop — and more forced selling.

Spreads on 30-year gilts jumped by more than 100 basis points in a week, to the highest levels in four decades. The Bank of England was forced to intervene and restore order to the market.

Others are less sanguine. “I don’t think it [LDI] is fully resolved,” says Aaron Rock, who is in charge of gilts at fund manager Abrdn. He believes the LDI crisis has made life tougher for those managing the UK’s finances and issuing new gilts via auctions. “Investors are worried about duration risk [the sensitivity of longer-dated gilts to interest rate movements],” Rock points out. “As a result, we are seeing bigger tails on auctions and more new issue premium.”

In the longer term, though, those issues will fade. Despite the hiccups of 2022, higher interest rates are overwhelmingly positive for pension funds as they reduce the size of future liabilities. This has put many DB schemes into an aggregate surplus and many companies are now transferring their pensions funds over to the insurance sector. With more funds closing and in run-off, this should mean lower demand for longer-dated gilts. That should make it easier for the DMO to sell less risky shorter-dated debt.

“The average maturity of UK debt is nearly 15 years because we had such high demand for long gilts — a very long-dated market compared to Germany and elsewhere,” says Jim Leaviss head of public fixed income at M&G. “Demand is already beginning to shift shorter. Some 30 per cent of the coming gilt issuance will be in the sub-seven year category, more than previous years. There will also be fewer index-linked gilts, which have been expensive due to interest payments linked to the soaring retail price index.”

30%

Percentage of coming gilt issuance with a sub-seven year duration

“Government borrowing will be a big topic this year,” Leaviss predicts. “We have the US debt ceiling coming up, which will shift the focus away from the corporate sector.”

In the UK, the government will hope it has a handle on the matter. Net borrowing (excluding refinancing) is expected to fall from £153bn in the 2022/23 financial year to £90bn in the 2024/25 period. Public sector net debt should peak at 103 per cent of gross domestic product in the 2023/24 period.

Gilt spreads remain contained, too. Although they are elevated at the longer 30-year and 20-year durations, compared with the pre-LDI period, the spread on 10-year gilts is now indicating business as usual.

Fears of a credit crunch have already cast doubt on any further hike from the Bank of England. Futures markets are pricing in the first cuts as early as the final quarter of this year.

“It’s all about the data,” concludes Rock. “If inflation starts to decline and employment softens, then the short end would start to come down. Further stresses in the banking sector would precipitate it.”

[ad_2]

Source link