[ad_1]

Size matters in fund management. The biggest investors, passive giants such as BlackRock, cater to the smallest, who are individual savers managing their nest eggs. The middle ground, which once yielded easy livings for active managers, has become a No Man’s Land.

US leviathans BlackRock and Vanguard have turned the industry upside down over the past decade. Their low-cost, index-based investments are luring trillions of dollars. Smaller rivals have to go big, go home or go specialist to justify steeper fees.

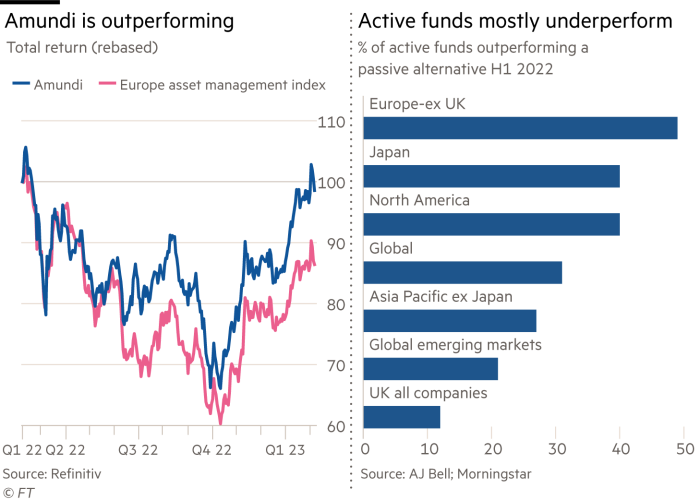

Amundi, which reported results this week, is one of the few able to go big. The asset management subsidiary of French bank Crédit Agricole managed €1.9tn (£1.68tn) of assets at the end of last year. That is €160bn less than at the end of 2021. Like most fund managers it has suffered from slumps in global stock markets.

Unlike many rivals, Amundi still managed to attract net new fund flows. These were €7bn for the year. Following in BlackRock’s footsteps, it is focusing on passive investments. These tend to be fixed baskets of stocks or bonds. The simplest are index trackers, following benchmarks such as the FTSE 100 or CAC40. Other funds have more complicated portfolios dictated by big data research.

Shares in fund managers are bets on securities markets whose volatility reflects the operational gearing of the companies. When earnings and valuations rise, so do securities prices. That swells the income that fund managers receive from annual management fees. Those revenues fall when securities prices slip.

To simplify: fund management shares are euphoric in a modest bull market and plunged into despair by the first hint of bearishness.

Those ups and down are merely cyclical. Lex thinks the secular trend for scale in fund management is unstoppable. For this reason, we like huge fund businesses such as BlackRock and Amundi, wealth management titan UBS and some US alternative asset groups.

We are also comfortable with such specialists as UK hedge fund group Man, which has some smart technology. We would avoid smaller UK generalists such as Jupiter and Abrdn. The latter is the disemvowelled result of the 2017 merger of Aberdeen Asset Management and Standard Life.

The transaction has not been a great success. The business has lagged behind rivals such as Schroders and been a target for short sellers.

More happily, Amundi acquired Lyxor for €825mn in 2021 to become a market leader in European exchange traded funds, a passive investment structure that trades on stock markets. Amundi now has some €300bn of passive assets under management, which it hopes to grow to more than €400bn by 2025.

Amundi reaps the benefits of banking relationships in distribution. In continental Europe, savings and investment products are still sold out of bank branches. That reach is also helping Amundi follow BlackRock into new revenue streams via technology sales. These grew 35 per cent last year to €48mn. BlackRock’s technology services division, known for its Aladdin platform, generated revenues of $1.4bn last year.

Though majority-owned by Crédit Agricole, Amundi’s shares are listed on the Paris Stock Exchange. These have tracked stock markets lower over the past year. But crucially, returns have outperformed European peers by about 15 per cent over that time. That reflects strife in the industry as well as Amundi’s scale.

BP chief executive changes his tune on renewables

Bernard Looney claims he is “leaning in” on his renewables strategy. Lean too far, and a person can end up staggering. Energy prices soared last year. But the shares of UK-listed oil major BP trail behind those of US rivals ExxonMobil and Chevron. Both have invested far less in green energy.

Looney’s messaging when announcing record full-year profits on Tuesday reflected that pressure. When the chief executive took over in 2020 he boldly promised to reduce crude production by 23 per cent to 2mn barrels daily by 2025. He planned to invest heavily in the energy transition. Two years on, his determination to forswear fossil fuels is weaker.

Record profits of £23bn last year were double what BP made in 2021 due to volatile oil and gas prices. The UK government is interested in a bigger slice via windfall taxes. BP’s effective tax rate already climbed two percentage points in the past year to 34 per cent, partly due to added levies. Exxon’s is closer to 26 per cent.

Oil and gas companies are operationally geared plays on hydrocarbon prices, in the same way that fund management shares amplify securities price movements (see above).

But total shareholder returns, which include dividends, for BP — and Shell — are roughly half those of Exxon and Chevron over one year. This reflects shareholder unease over renewables investment as much as over windfall taxes. BP has increased the outlook of $16bn-$18bn for capital spending this year from a target of $14bn-$16bn back in 2020.

Some of that increase comes from inflation. But oil production for 2025 would now fall only about 11 per cent from 2019 to 2.3mn barrels per day. Those volumes are needed, oil bulls say, to cover the west’s lost supply from Russia. BP’s oil price assumption for income from those added barrels has risen from $60 to $70.

Higher forecast upstream profit helps pay for Looney’s renewables spending, an additional $8bn cumulative by 2030. Nearly half of this money goes to hydrogen and renewable power areas.

Looney read the presentation room well, if not the mood of green campaigners perturbed by prevarication. The share price jumped 8 per cent on the day. The reality is that the marginal buyer of BP’s shares believes the energy transition will take longer, with scope for increased oil and gas output. BP is compromising in a bid to catch up with US peers.

Lex is the FT’s concise daily investment column. Expert writers in four global financial centres provide informed, timely opinions on capital trends and big businesses. Click to explore

[ad_2]

Source link