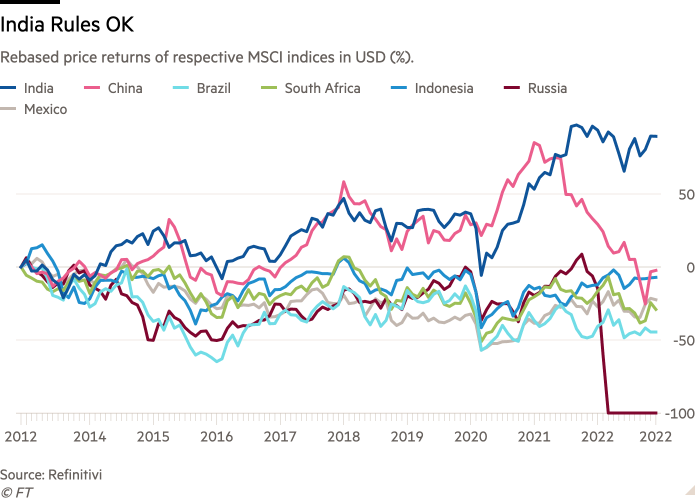

Huh. We didn’t this coming: India has quietly become an emerging-market standout over the past decade. Not only has it easily posted the best performance of any major EM, it’s also been pretty much the only one to generate positive returns.

If you knew this already, congratulations! You’re either an EM equities manager or better-informed than FTAV (perhaps not the highest hurdle to clear, but let’s not dwell on that).

Here are some of the respective MSCI indices, rebased from Dec 3, 2012.

That Indian equities are having a pretty decent 2022 was covered by our mainFT colleague Chris Flood earlier today, at least partly on bets that India may win from “friend-shoring” of western manufacturing hubs.

But the long-term outperformance (relative to other big EMs, at least) runs counter to received wisdom. India’s stock market has a reputation as a perennial dumpster fire, its economy is known as a stubborn underperformer, and its status as the “world’s biggest democracy” comes with a strong implication of very messy politics.

That’s unfair, argues Morgan Stanley’s Ridham Desai in a report that landed in our inbox on Sunday (his emphasis below):

India is set to become the world’s third-largest economy and stock market, with GDP of more than US$7.5 trillion and an equity market cap of US$10 trillion. It is poised to drive about a fifth of global growth in the coming decade. Many investors view India as a market that disappoints expectations, but we see it as a quintessential self-help story. The fact is that over the past 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 years, India’s growth has only lagged China’s among large economies, and we believe that India can continue to deliver outperformance. It is one of the few countries in the world that is gaining from the disruptive global trends of demographics, digitalisation, decarbonisation and deglobalisation. More importantly for investors, MSCI India is among the top ten MSCI country indices in US dollar terms across all these timeframes — a position shared only by the US and Denmark.

Morgan Stanley admits that “things could go wrong”, such as a global recession that hits India hard, messy domestic politics, policy errors, skilled labour shortages and energy price spikes.

But the bank still reckons that India’s GDP per capita is going to more than double to $5,242 by 2031, with the number of middle-class households rising to 165mn and rich households quintupling to 25mn. Morgan Stanley thinks that “the New India” benefits from three main factors:

First, India is likely to increase its share of global exports, thanks to a surge in offshoring: The pandemic only enhanced India’s attractiveness as the office to the world as CEOs became comfortable with work from home. New developments are also allowing India to gain traction as a factory to the world. They include government incentives and the trends underpinning Morgan Stanley’s multipolar world thesis.

Second, India is pursuing a distinct model for the digitalisation of its economy, supported by a public utility called IndiaStack: Operating at population scale, IndiaStack is a transaction-led, low-cost, high-volume, small-ticket-size system with embedded lending. The digital revolution has already changed the way India handles documents, invests and makes payments, and it is now set to transform the way it lends, spends and insures. With private credit at just 57% of GDP, a credit boom is in the offing.

Third, India’s energy consumption and energy sources are changing in a disruptive fashion, with broad economic benefits: On the back of greater access to energy, per capita energy consumption is likely to rise by 60% to ~1,450 watts per day over the next decade, on our estimates, with two-thirds of the incremental supply coming from renewable sources. We believe that this shift will benefit India’s terms of trade, entail about three-quarters of a trillion dollars in energy capex and eventually reduce headline inflation volatility as the imported energy share of GDP declines.

The problem is that the link between GDP growth and stock market returns is murky at best.

Otherwise Chinese equities would have been a world beater over the past decade, rather than having actually destroyed value over that period. In fact, the MSCI China index is today lower than it was since its inception in 1994, despite GDP growing nearly tenfold over that period.

And the current bout of optimism around “the New India” has a heavy whiff of “Brazil Takes Off” hype about it. The Bovespa has roughly halved since this infamous Economist cover. Morgan Stanley beware.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.