[ad_1]

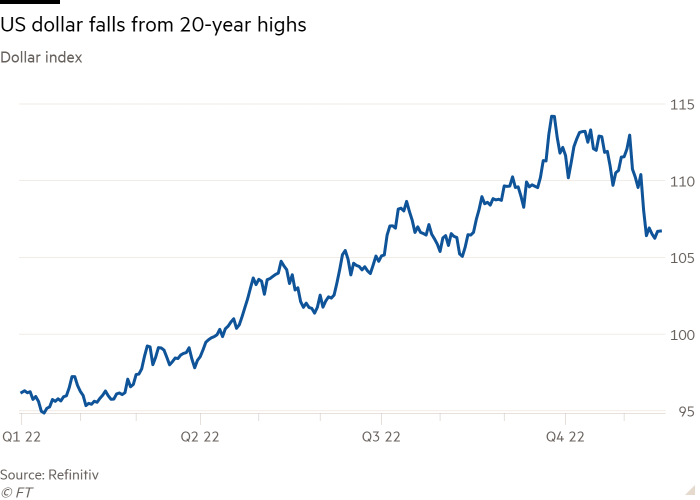

The dollar has tumbled in the past fortnight from a 20-year high as signs of inflation easing in the US fuel speculation that the Federal Reserve will soon slow down its rate rises.

The greenback has fallen more than 4 per cent against a basket of six peers so far in November, leaving it on track for the biggest monthly fall since September 2010, according to Refinitiv data. It is still up about 11 per cent for the year to date.

This month’s fall comes as investors scrutinise early indications that US inflation may finally be easing, potentially paving the way for the Fed to reduce the speed at which it has been boosting borrowing costs. Some data, such as those on the housing and manufacturing sectors, have also suggested the broader economy is facing rising headwinds, another deterrent to Fed monetary tightening.

“Everything is pointing to disinflation in the US and with that we will see a slowdown in the US economy in the first quarter of next year . . . That forms the basis for the weaker dollar story,” said Thierry Wizman, a strategist at Macquarie.

The dollar’s drop has alleviated some of the pressure on a global economy that was creaking under the strain of a strong dollar, which helps to drive up inflation in smaller economies and adds to debt sustainability problems for countries and companies — particularly in emerging markets — that have borrowed heavily in the US currency.

The euro has risen to nearly $1.04 after sinking below 96 cents in September, and the UK pound’s recovery from September’s all-time low gained further momentum. The yen has rebounded somewhat from a slide to a 32-year low against the dollar that had prompted the Japanese government to spend billions propping up its currency.

Still, much depends on how the Fed reacts to data showing US consumer and producer prices grew at a slower annual rate in October than September — and whether that trend continues. At the central bank’s November meeting, chair Jay Powell did not explicitly signal a fifth consecutive 0.75 percentage point increase, which traders understood as a sign of the Fed’s openness to a half percentage point rise as soon as next month.

Indications of easing inflation have also upended wildly popular wagers in currency markets on a stronger dollar.

“We expect the US dollar’s powerful climb over the past year to reverse in 2023 as the Fed’s hiking cycle comes to an end,” HSBC foreign exchange strategists wrote in note to clients this week. “It has peaked.”

In recent weeks, traders have trimmed their bets on a stronger dollar to the lowest level in a year, according to figures from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which provide a snapshot of how speculative investors such as hedge funds are positioned in currency markets.

The greenback’s historic ascent earlier this year came as a wave of rapid price increases swept the globe, prompting big central banks — with the notable exception of the Bank of Japan — to rapidly tighten monetary policy. But rate rises elsewhere were largely unable to keep pace with the Fed, which thanks to the relatively robust US economy was able to lift borrowing costs faster than peers in other developed economies, bolstering the appeal of the dollar.

At the same time, fears of a global recession and the financial market volatility unleashed by rapid monetary tightening also favoured the US currency, which as the ultimate safe harbour of the global financial system tends to rise in times of stress.

Both those tailwinds are now set to fade, according to HSBC, which argued that “gravity should take hold” for the dollar as the often chaotic sell-off in global bond markets, caused in part by central bank rate rises, calms.

Despite the about-turn in markets, a few hawkish speeches from Fed officials in recent days have tempered bets that the Fed is slowing down.

The dip “looks like an overreaction given Fed speakers so far have made it clear the job is not done”, said Athanasios Vamvakidis, head of G10 foreign exchange strategy at Bank of America.

While the dollar may not surpass the 20-year high it hit in late September, Vamvakidis warned that inflation remained high. “We are not out of the woods yet . . . Even if inflation has peaked it will be sticky and volatile on the way down.”

With traders firmly focused on month-by-month US inflation figures, a slight upside surprise could easily cause the entire global currency market to skew back in the other direction, he added.

That sentiment was evident in remarks by St Louis Fed president James Bullard on Thursday, who said that rates would need to be raised to a minimum of 5 per cent in order to tame inflation.

Positions in the futures market currently reflect that investors see interest rates peaking at 5 per cent in May.

“It’s premature to call a peak in the dollar, because the Fed expects further rate hikes,” said Joe Manimbo, an analyst at Convera.

[ad_2]

Source link