[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Some nasty selling in tech yesterday, though just about all of it after hours. If the pattern holds after markets open today, things could get ugly. Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Bear market rally redux

Markets are feeling better all of a sudden. The S&P 500 is up 10 per cent from its lows of two weeks ago, and 5 per cent above where it closed last Thursday. One big reason appears to be this:

Federal Reserve officials are barrelling toward another interest-rate rise of 0.75 percentage point at their meeting Nov. 1-2 and are likely to debate then whether and how to signal plans to approve a smaller increase in December …

“The time is now to start planning for stepping down,” said San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly during a talk at the University of California, Berkeley on Friday.

That’s from an article the Wall Street Journal ran on Friday, which markets took as unofficial Fedspeak.

If the Fed is close to shifting its monetary stance, that’s a big deal. But to us, recent days feel unpleasantly reminiscent of the bear market rally that began with June hopes and ended in August tears. At the time, the market looked at softening economic data and dreamt that falling inflation, and a Fed pivot, would follow. They didn’t, and as more hot inflation and jobs numbers sank in, equities fell to new lows. Are we set for a repeat?

Bulls, arguing that this time is real, might note that two big things have changed since June: the macro picture and earnings.

The economy has kept slowing. In some areas, it is shrinking. The S&P purchasing managers’ index for October, published Monday, fell deeper into contraction, led by declining services activity. And even though official CPI figures are still high, other signs of falling inflation are piling up. Preliminary October rents data from Apartment List showed the sharpest month-on-month drop in five years, according to Bloomberg. Inflation expectations for 2023 reached 5.5 per cent back in June. Now bond markets expect just 2.7 per cent inflation a year from now.

Meanwhile, earnings have, for the most part, held up. Last week, the big US banks reported impressive profits and basically no signs of a consumer slowdown. Yesterday’s Microsoft earnings showed resilient revenue growth on the back of growing cloud services demand (though the stock got caught up in after-hours tech selling). Unbothered by FedEx’s dire profit warning, UPS, which also reported yesterday, raised prices to offset falling package volume while offering perky guidance for the fourth quarter. Pepsi, Coke, Sherwin-Williams, Procter & Gamble and various other demand bellwethers have done just fine — despite some stinkers in goods, such as Whirlpool.

If you squint, you can see the case for stocks: rates really are about to peak, and earnings have enough strength left to power a fresh rally.

Unhedged doesn’t buy it. Inflation, as we’ve argued, is going to be a slow grind down, suggesting that interest rate cuts are not coming soon. Rates will need to stay higher for longer, as Fed officials have said. That means unceasing pressure on demand and earnings — even if rates start climbing more slowly (in 25 basis point or 50 basis point increments, say). Put simply: for inflation to fall, demand must fall, and so too must earnings.

Google’s earnings yesterday provided a glimpse of the future. The search advertising company significantly undershot expectations. YouTube ad spending fell and, excluding a brief contraction at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, total revenue grew at the slowest pace since 2013. A 7 per cent drop in after-hours trading (which, we should say, is not always a great indicator) followed, pushing the stock back to where it was on October 14.

All the optimism built up in the past two weeks got knocked right out of Google stock after a single dose of disappointing data. Many more such cases are coming, if not in this quarter, then in the next year. (Ethan Wu)

US house prices are unlikely to crash

It must be admitted at the outset that this chart is not wonderfully encouraging:

US house prices fell by about 1.3 per cent between July and August, according to the gold standard index, the Case-Shiller. That is not too far from the biggest monthly declines we saw during the housing crisis 15 years ago. Back then, we had a lot of those monthly declines all in a row, adding up to a peak-to-trough national decline of almost 30 per cent. But there is good reason to hope that the decline this time around won’t be anywhere in that (very bad) neighbourhood.

The reason to think that there will be a house price crash is that the increase in mortgage rates this year has been bonkers. The 30-year fixed rate has gone from 3 per cent to 7 per cent in 10 months! Home sales have responded. They were down 24 per cent in September, according to the National Association of Realtors. Does it not make sense that a crash in prices would follow this crash in transactions?

The case against a price crash, as distinguished from a mere decline, has been made by Innes McFee of Oxford Economics in a recent note to clients. It is based on a basic truth of markets: the absence of buyers is not sufficient for a price crash. For a crash, you also need forced sellers. So, in the case of housing, insane mortgage rate increases are not enough; you also need a lot of people to get fired and suddenly be unable to pay their mortgages. Employment is the key.

McFee looked at previous global developed-market housing crashes (defined, quite conservatively, as an annual decline of 10 per cent or more) over that past half century, and tracked the economic variables that accompanied them. What he found was that big declines in the level of employment — a median of 5 percentage points — were a feature of almost every crash. Mortgage rates were not nearly as determinate. He writes:

In half of the historical episodes that we have examined, mortgage rates fell in the first six months of the crash. In others, such as the house price crashes seen in Southern Europe during the debt crisis, rising mortgage rates were a key driver of the downturn. This mixed picture reflects the fact that higher interest rates will also be associated with growing economy an potentially signs of exuberance in the housing market.

In the US the employment level is exactly where it was before the pandemic (159 million people). There are few forced sellers. This helps explain, in part, why the housing crash forecasting model based on McFee’s analysis puts the probability of a 10 per cent crash in US house prices at just 35 per cent. The odds for Sweden, New Zealand and Canada are all over 50 per cent.

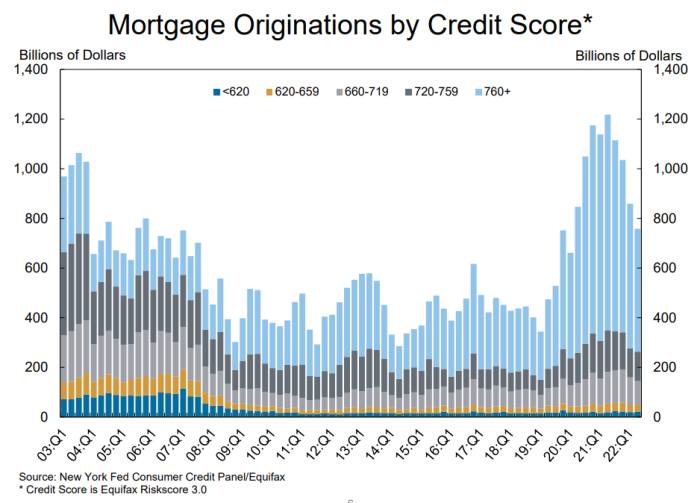

And as McFee pointed out to me, there are important factors that the model does not capture, which may mitigate US risks further. One is the prevalence of long-term fixed-rate mortgages in the US. They are rarer elsewhere. Another is that the very fast increase in home prices in the past several years means buyers of more than a few years’ standing will have built up a significant equity buffer in their homes. Finally, there is the notable increase in the creditworthiness of US home buyers in recent years. Here is a chart from the New York Fed:

House prices will fall more from here and this will cause economic pain. That’s how monetary policy works. But a hard crash — much more than 10 per cent, say — looks unlikely.

One good read

Tight labour markets are good.

[ad_2]

Source link