[ad_1]

On the golden sands of the French Riviera, just along the beach from an evening game of volleyball, dark-suited private equity executives crowded into a marquee for a drinks reception and did their best to ignore the crisis hitting their industry.

Cocooned at a conference this week in one of Europe’s most exclusive destinations, top dealmakers exuded confidence even as the conditions that fuelled a decade-long private equity boom went into reverse.

For years, almost everything has gone right for the buyout industry’s billionaire bosses. Now, as rates rise and their model faces its biggest test since at least the 2008 crash, private equity is looking to what dealmakers hope will be their next revolution: an unprecedented wave of money from retail investors.

“When the markets stabilise it will be a tremendous time for private equity” and an influx of retail money is “a matter of when”, not if, Verdun Perry, global head of Blackstone Strategic Partners, said on the conference’s main stage this week.

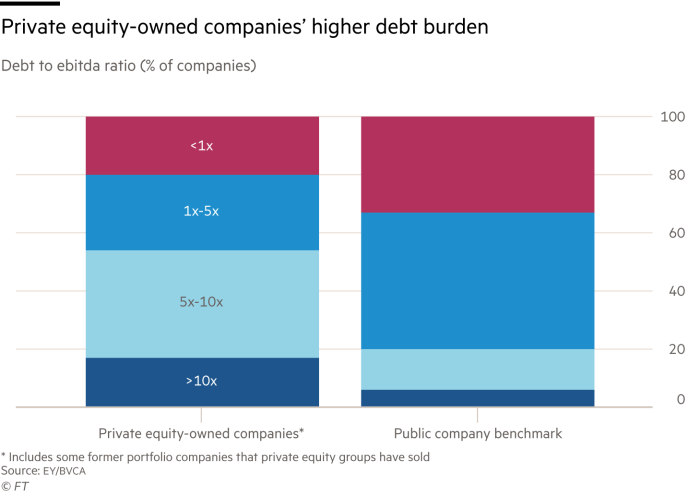

Buyout groups have spent the past few years striking record numbers of deals at often eye-watering valuations, using growing amounts of debt. Now, they are holding businesses whose borrowing costs are rising just as their earnings fall.

Investors specialising in distressed debt could barely contain their glee at the prospect of these companies falling into trouble.

“For the first time since the global financial crisis and for very different reasons, we are beginning to see cracks in a real way across the board,” said Matt Wilson, a managing director at Oaktree, during a panel discussion at the event.

“The confluence of lower earnings, lower cash flow and higher borrowing costs is going to be a very challenging situation,” he said. “We’re very excited about what we see in front of us right now . . . it’s hard to see a path to a soft landing.”

And as some argue that the top of the market has been reached, others are becoming concerned about the industry’s practices.

Mikkel Svenstrup, chief investment officer at Denmark’s largest pension fund ATP, used his platform at the conference to compare private equity to a pyramid scheme.

He complained about the industry’s use of “continuation funds”, a fast-growing model in which a private equity group sells a company to itself by shifting it between two of its own funds. And he said he was “looking very carefully” at “all those tricks they do to kind of manipulate” returns figures.

Speaking privately on the sidelines of the event, however, a top executive at a European buyouts group said he was confident that “the golden age of private equity is just beginning”.

One of the main reasons for optimism is the hunt for cash from individuals — in contrast to the pension funds, endowments and sovereign wealth funds that have so far propelled the industry’s growth — what senior figures describe as the “democratisation” of private equity.

Some of that money will come from the very wealthy. Morgan Stanley and Oliver Wyman said in a report last year that people with between $1mn and $50mn to invest would in total commit an extra $1.5tn to private markets by 2025.

But the industry is also targeting people much further down the income ladder.

“We’re talking real democratisation,” Virginie Morgon, chief executive of the buyouts group Eurazeo, said at the conference. The industry would raise money from “not, like, high net worth individuals” who can invest €1mn or more, but people with €5,000 or €10,000, she said.

Ariane de Rothschild, who chairs the Franco-Swiss private bank and asset manager Edmond de Rothschild, warned of the need for “a strong governance framework in order to avoid misunderstandings and potential reputational damage” when ordinary investors are being brought in.

There was even talk of retail investors buying into continuation fund-related products, which are so specialised that many people in the finance industry have little understanding of how they work.

“In many ways I think that product almost makes more sense for retail investors” than buying into private equity funds, said Gabriel Mollerberg, a Goldman Sachs managing director who also specialises in the deals. The vehicles are less volatile and more diversified, he said.

Amid the parties and panels, executives warned that the industry was caught in limbo as private valuations — of the companies buyout groups own and of unlisted private equity firms themselves — have not fallen in line with public markets.

“It’s been a very tough year for a lot of [stock market] investors,” said Svenstrup, from ATP. “It’s kind of interesting, right, because private markets seem to still keep their valuations . . . Eventually they will converge. Whether that’s to the upside or the downside, time will show.”

During the conference, Goldman Sachs’ Petershill Partners, a London-listed group that owns minority stakes in private equity firms, reported an accounting loss as it marked down the value of its investments.

The move highlighted how rising interest rates have made buyout firms, which receive a steady stream of cash from the management fees they charge investors, less valuable. Shares in Blackstone, Apollo Global Management, KKR, Carlyle Group, EQT and Bridgepoint have all fallen this year by more than the S&P 500.

The valuations of privately held buyout groups have not necessarily followed.

“One thing we’ve been asked about a lot recently is, has our valuation, our approach changed with what’s happening in the public markets?” said Tiffany Johnston, a managing director at Blue Owl, which buys minority stakes in private equity firms. “And it really hasn’t . . . we’ve found we’ve just been able to be very consistent.”

As even insiders question the industry’s model — amid hopes to lure in retail investors — private equity is formulating its defence.

George Osborne, the UK’s former chancellor who was at the conference as a partner at his brother’s venture capital firm, 9Yards Capital, said the industry had to invest “for the longer term”, looking through the energy crisis, inflation and the “tragic problem” of the war in Ukraine.

Orlando Bravo, co-founder of buyouts group Thoma Bravo, which ploughed tens of billions of dollars into software deals at the peak of the market in the past few years, was among the most bullish at the event.

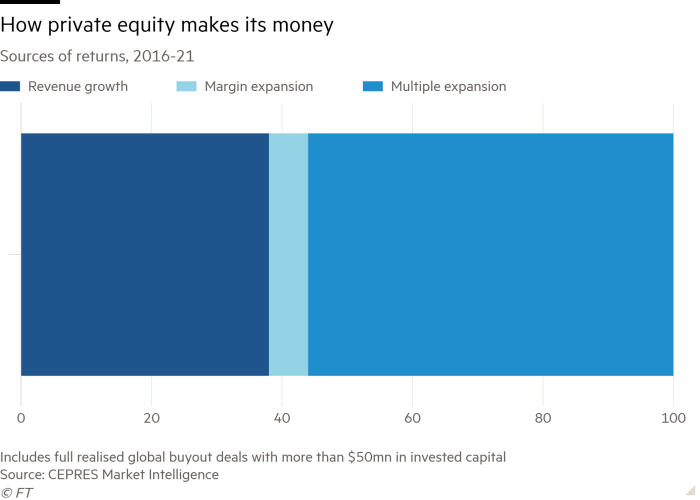

“The way our industry makes money is not by timing the market,” he said, adding that private equity had made some successful deals at high valuations and unsuccessful ones cheaply. “You buy a great business when you can . . . our industry’s not about buying high and selling higher, it’s never been about that.”

Figures from Bain & Co tell a different story. So-called “multiple expansion”, or selling a company at a higher multiple of its earnings than it was purchased for, has been “the largest driver of buyout returns over the past decade”, a report from the consultancy said this year.

Bravo, however, dismissed Svenstrup’s comparison of private equity to a pyramid scheme, saying: “Oh my gosh, the opposite. It’s the best way of ownership in the world!”

Additional reporting by Chris Flood

[ad_2]

Source link