[ad_1]

Liz Truss pledged to prioritise soaring energy bills for households and businesses in her acceptance speech as Conservative party leader before she is installed as the UK’s new prime minister on Tuesday.

“I will deliver on the energy crisis dealing with people’s energy bills, but also dealing with the long term issues we have on energy supply,” she said.

Truss is expected to act quickly ahead of the impending 80 per cent increase in the average annual domestic energy bill from the start of October. Her team has indicated that she will outline her plans on Thursday with a support package that could reach £100bn.

What are the options for Truss?

Energy suppliers, including ScottishPower and Ovo, have called for a loan scheme to freeze or significantly reduce bills for households.

This could take many different forms but the common element in the various options is for the government to provide loans or loan guarantees to suppliers so they could hold the cost of energy for a household with a typical level of consumption at the existing domestic price cap of £1,971.

Broadly, Truss will have to choose between a simple freeze on all bills or a more targeted scheme aimed at poorer families, by for example limiting the number of subsidised units of energy each household would receive.

What is most likely to happen?

Up to now, the UK government has opted for a blend of blanket and targeted support. This includes a £400 rebate on energy bills this winter for all households and additional means-tested payments through social security benefits such as universal and pension credit. The support offered so far, which also includes fuel duty and council tax rebates, will cost £37bn, according to the Treasury.

The imminent rise in bills and the difficulty in assessing the situation of households with high energy use has led the Labour party and the Liberal Democrats to propose a freeze on all bills. This has become increasingly attractive to the Truss team rather than the complexities of a more targeted approach not least as the average bill in January is forecast to exceed £5,000, according to the Resolution Foundation.

There is also an urgent need to help businesses, which are not covered by the price cap and are facing even bigger increases in their bills. Kwasi Kwarteng, the favourite to be Truss’s chancellor, hinted in the Financial Times that companies would not be forgotten, promising help to “get families and businesses through this winter and the next”.

Gerard Lyons, an economist advising Truss, has proposed an effective cap on the price of wholesale gas which would benefit both companies and households.

Who will it help?

The winners and losers will depend on the design of government aid. If the new plan is to freeze bills, this will offer the broadest support but will benefit the biggest energy users most and come with the highest price tag.

Universal payments, such as the £400 rebate already offered, are of most value to richer families with low energy bills and of least help to more vulnerable customers in old and draughty homes.

Targeted payments such as the £650 for those on means-tested benefits help only the poorest and cost much less. But they offer no help to families who are struggling financially but fall just outside the benefit safety net.

Will it be inflationary?

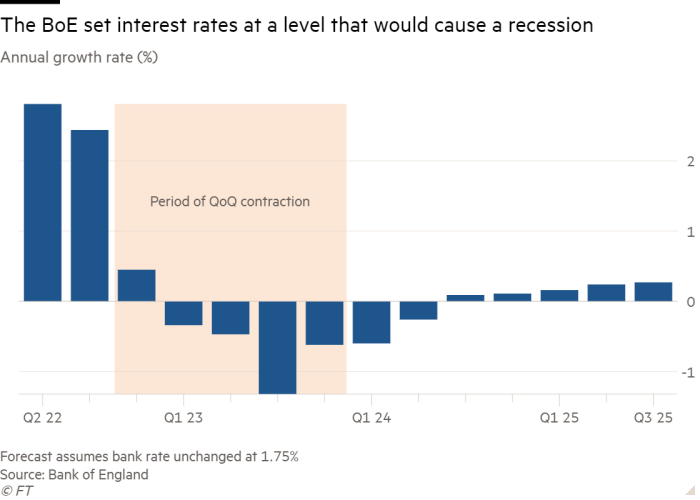

Additional government borrowing or state guarantees on private sector loans would increase spending in the economy at a time the Bank of England thinks there is excess demand. As a result, the central bank would probably respond to these inflationary pressure by raising interest rates, with Goldman Sachs on Monday forecasting they would reach 3.25 per cent by the end of the year.

Paradoxically, a support scheme that resulted in freezing energy bills would lower measured inflation and as a result hold back the forecast rapid rise in the headline rate from 10.1 per cent in July to around 15 per cent or higher at the start of next year.

Jens Larsen, a director at Eurasia Group, the consultancy, said a lower official measure would help stem inflation expectations that could in turn create a wage-price spiral, but added: “The MPC will still want to raise rates in response to a fiscal package that is likely to be very expansionary.”

Another potential problem is the effect any plan would have on the global markets’ view of UK assets. Whichever way the subsidy is applied, borrowing to pay for imported gas would worsen the trade deficit, leading to concerns that the country could be living beyond its means.

Deutsche Bank on Monday warned of the dangers of “a self-fulfilling balance of payments crisis whereby foreigners would refuse to fund the UK external deficit”.

What will it cost?

ScottishPower suggested that if the new prime minister wanted to freeze bills at £1,971 for all households for two years, such a “deficit fund” would cost more than £100bn.

The scale of the support would depend significantly on how the government decides to help business, because industrial and service sector companies use two-thirds of the amount consumed by households.

Ultimately, it will depend on the exact scheme chosen by Truss. But even then even the government cannot be certain of the level of support it would need to provide as it would depend on the price of wholesale gas, which has been extremely volatile.

There are some measures that would offset the overall cost, including the £5bn windfall tax on North Sea oil and gas producers announced by the government earlier this year.

Kwarteng has also been working on a scheme that would cut the cost of electricity by limiting how much renewable and nuclear power producers are paid for their output, a move Energy UK, a trade body, estimates would save up to £18bn annually from next year.

How would any scheme be funded?

The government would prefer a loan guarantee scheme so that the private sector could take on the debt so it does not show up in the public finances. This would allow Truss to argue she is not borrowing and spending, as the ONS would be likely to classify such a scheme as a contingent liability. That is as long as the transaction was genuinely in the private sector and would not ultimately require a state bailout.

The downside is that it would be more expensive for the private sector to borrow than the government, leaving a bigger bill for households to pay in future either through general taxation or via levies on energy bills.

[ad_2]

Source link