[ad_1]

Investors are preparing for a longer period of high interest rates than expected after the US central bank chair delivered his most hawkish speech to date, vowing to ensure elevated prices do not become entrenched.

Jay Powell on Friday put an end to any hopes that the Federal Reserve would step back from its dramatic tightening of monetary policy anytime soon, as he reaffirmed his “unconditional” commitment to tackling high inflation.

“The theory of a dovish pivot has been squashed,” said Brian Kennedy, a portfolio manager with Loomis Sayles. “Powell is a creature of history and to me this is further confirmation that the Fed does not believe inflation is rolling over and going back to 2 per cent.”

The eight-minute speech sparked a dramatic stock sell-off with the benchmark S&P 500 sliding more than 3 per cent — its biggest drawdown since the June rout, when $14tn in value was erased from the US stock market. Hopes that the Fed may relax its stance as the economy slows were shattered. All but six of the companies within the stock benchmark dropped, with shares of economically sensitive homebuilders falling nearly 5 per cent and chipmakers declining more than 6 per cent.

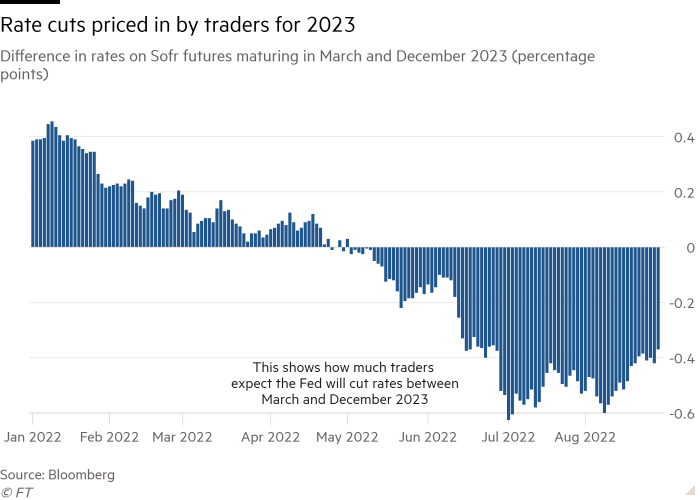

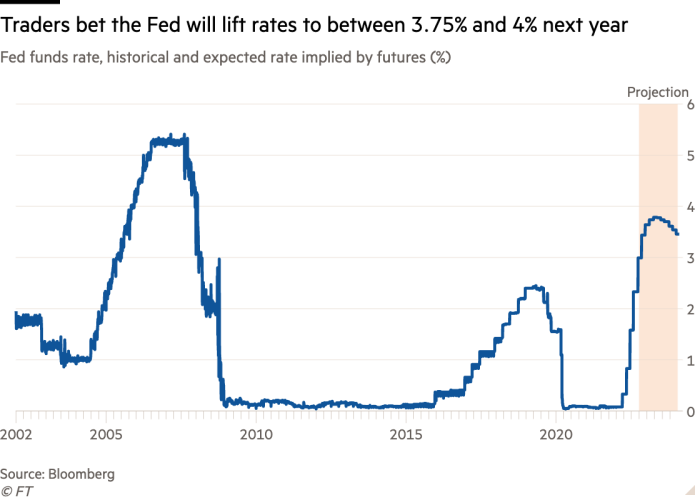

Traders in futures markets shifted their bets as well. While they still expect the Fed to lift rates to between 3.75 and 4 per cent in the first half of next year, they began to dial back their wagers that the central bank would begin to start cutting rates later that year and into 2024 as they previously bet.

“It could not be clearer that they are going to keep raising rates and running down the balance sheet until they get clearly on top of inflation,” said Bob Michele, the head of JPMorgan Asset Management’s global fixed income, currency and commodities unit. “This fantasy that they will start cutting rates a couple months after the last rate hike is nonsense.”

Michele added the fact that futures and Treasury markets did not react more forcefully to Powell’s speech underscored the credibility problem the Fed chair still faced. Powell and his colleagues have run into criticism for arguing last year that inflation would prove transitory and ultimately fall back towards the Fed’s 2 per cent target.

The more muted move in Treasuries could also reflect the brutal sell-off they have already faced this year, money managers said, with the yield on the two-year note trading just below a 14-year high struck in June.

The market ructions followed Powell’s long-awaited speech at the first in-person Jackson Hole symposium of global central bankers since the start of the pandemic, in which he stressed the Fed “must keep at it until the job is done” on inflation. He also acknowledged that tackling inflation will probably have economic costs, including a “sustained period of below-trend growth”.

“While higher interest rates, slower growth, and softer labour market conditions will bring down inflation, they will also bring some pain to households and businesses,” he said. “These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain.”

Citing the tumult of the 1970s — in which the Fed made errors by easing policy prematurely in order to shore up growth but before inflation had moderated sufficiently — Powell vowed to avoid that outcome. He also reiterated that rates will need to stay at a level that restrains growth “for some time” and emphasised the high bar in terms of the economic data to justify shifting to a less-aggressive stance.

Julian Richers, an economist with Morgan Stanley, said Powell’s speech helped dispel the view the Fed might be swayed to loosen policy as the economy slows. Powell’s comments following the Fed’s July meeting helped propel a relief rally.

“This whole debate of a Fed pivot in July never really made sense,” he said. “If you were hanging your hat on the Fed being uber-dovish, that’s a course correction.”

Fed officials have yet to decide whether a third consecutive 0.75 percentage point rate rise is necessary at the next policy meeting in September or if they can begin shifting away from the “front-loading” phase of the tightening cycle and scale back to a half-point rate rise. In just four months, the federal funds rate has increased from near-zero to a target range of 2.25 per cent to 2.50 per cent.

Economists believe further rate rises will be necessary in 2023 in order to quell inflation, which they warn is at significant risk of persisting longer than anticipated.

Most have pencilled in a recession at some point in the next 12 months, with the unemployment rate rising well beyond its historically low level of 3.5 per cent.

“The great unknown is how much the economy actually will slow in the near-term and at what point does the Fed acknowledge that,” Loomis Sayles’ Kennedy said.

[ad_2]

Source link