[ad_1]

Sri Lanka’s debt default and political implosion have reignited fears that other emerging market countries could be heading into similar trouble as blistering inflation and rising US interest rates send investors fleeing.

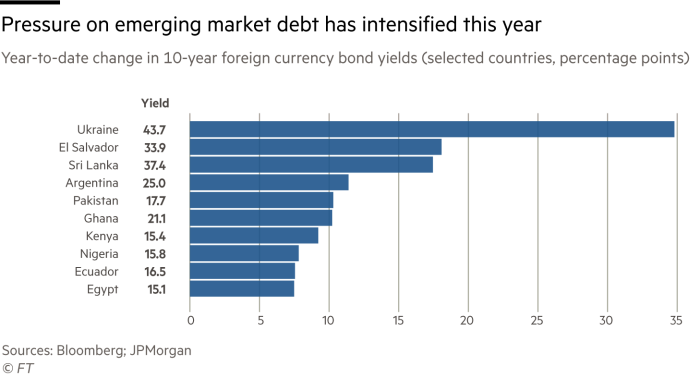

Sovereign bond yields have ballooned to levels that point to intensifying strains across more than a dozen developing economies, according to a Financial Times analysis of Bloomberg data.

Emerging market investors are used to volatility, but the asset class is now being buffeted by multiple crises at once. The tumult has prompted investors to pull $52bn from emerging market bonds this year, according to JPMorgan data.

“It’s pretty shocking to see this scale of a collapse in bond prices,” said Charlie Robertson, global chief economist at Renaissance Capital, adding that the sell-off is “one of the biggest I’ve seen in 25 years”.

The war in Ukraine has sent food and fuel prices soaring with devastating social and fiscal consequences for the many developing countries that depend on imports. While some oil exporters, particularly those in the Gulf, have benefited from rising prices, others have seen the gains partly or wholly eradicated by pandemic-related disruption.

The Federal Reserve’s move to raise interest rates in an effort to tame surging inflation has also led to a strengthening US dollar. This has piled further pressure on emerging market economies that must service their dollar-denominated debt, while tightening financial conditions are hurting developing countries already starved of capital.

“Emerging markets do not like the Fed hiking rates and do not like it when the dollar’s strengthening,” said Robertson, adding that “it’s just bad news for countries that need capital when that happens, and we haven’t seen rate hikes like this in nearly 30 years”.

The yield on 10-year foreign currency bonds of at least six emerging market countries have jumped by more than 10 percentage points since the start of the year, according to Bloomberg data, including Ukraine, Argentina and Pakistan.

Although bonds in more than a dozen countries are trading at distressed levels that typically signal a high probability of default, analysts suggest that actual missed payments and restructurings are likely to be more isolated. Many large emerging economies are in better fiscal and monetary shape today than in past crises, making them better able to withstand today’s serial shocks.

“There are big fiscal strains, particularly in frontier markets,” said William Jackson, chief emerging market economist at Capital Economics, referring to less developed emerging markets. “But [for the likelihood of default] you have to look at countries case by case.”

Esther Law, senior investment manager for EM debt at Amundi, said stress in bond markets was less a signal of imminent defaults than a sign of concern over recession and inflation in the US, slow growth in China and disruption and shortages caused by the war in Ukraine.

“This is more a sentiment thing than a fear that countries will fall into default,” she said. “But if this is prolonged, obviously it will increase funding costs for those countries and that will feed back into their ability to pay.”

Emerging markets under pressure

Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sent Kyiv’s bond yields soaring as investors flee the war-torn country’s debt. Despite this, the IMF said on Thursday that it expected Ukraine to continue servicing its debts and that extra funding would help the country function without needing to issue more bonds.

El Salvador

El Salvador’s multimillion-dollar bet on bitcoin has backfired as the cryptocurrency has halved in value so far this year, worsening the Latin American country’s economic situation. El Salvador’s 10-year bond yield has surged by more than 18 percentage points so far this year as investors dump the debt.

“The adoption of bitcoin as legal tender has added uncertainty about the potential for an IMF program that would unlock financing for 2022-2023,” Fitch analysts said.

The country has an $800mn bond set to mature in January, with analysts also concerned about its ability to repay.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka has been mired in political and economic chaos and defaulted on its debts in May. Its president fled the country this week, leaving in his wake millions of people struggling for food and fuel, and throwing into chaos the nation’s debt restructuring talks with creditors.

Sri Lanka has a $51bn debt pile, half of which is owned by bilateral creditors including China and the rest by asset managers including Pimco.

The Asian country needs to form a new government in order to secure financing from the IMF, which would enable it to advance restructuring talks with creditors. “We’re back to square one,” said one bondholder.

Argentina

Argentina is no stranger to debt defaults. The country went through a restructuring in 2020 and agreed a deal with the IMF earlier this year, helping it escape another collapse. Its 10-year bond is at present trading below 20 cents on the dollar, in deeply distressed territory.

Argentina’s new finance minister has promised to bring order as the country struggles under rocketing inflation — set to exceed 75 per cent this year.

Pakistan

Pakistan agreed a deal with the IMF on Thursday, paving the way for $1.2bn to be released in order to help the country avoid defaulting. The surging cost of importing oil and other commodities has widened Pakistan’s trade deficit and fuelled fears that it could suffer the same fate as Sri Lanka.

Its IMF agreement is hoped to encourage other lenders to invest in the country and stave off a default.

Under the greatest duress is Ukraine, which since Russia’s invasion in February has been begging foreign governments for cash to meet its soaring budget deficit, at present running at $9bn a month, up from $5bn in the early stages of the war. The yield on its 10-year bond has surged by more than 30 percentage points since the start of the year, reflecting investors’ fears.

State utility Naftogaz asked bondholders to accept delayed payments last week, raising fears that the government will miss bond payments due on September 1 of $1.4bn, according to Bloomberg.

The IMF said on Thursday it expected Ukraine to keep meeting its sovereign debt payments. The fund said it expected more donations in the coming days to an account it set up to support the country in April. It added that grant financing rather than loans should be the priority in the short term — the EU has delivered only $1bn out of $9bn pledged in April because of disagreements over whether to provide grants or loans.

The bond yields of Pakistan, Egypt and Ghana are also spiralling higher. On Thursday, Pakistan reached an agreement with the IMF which paves the way for the country to access crucial funds and avoid a potential default.

“The IMF has become the world’s firefighter,” said Robertson. “Even those who didn’t want them are now inviting them in because they saw Sri Lanka fail to do so.”

Markets suggest that Argentina’s risk of another default is also high. The yield on its 10-year bond has soared by more than 10 percentage points so far this year while the price has plunged to below 20 cents on the dollar.

Kristalina Georgieva, head of the IMF, sounded the alarm this week, saying: “The situation is increasingly grave for economies in or near debt distress, including 30 per cent of emerging market countries and 60 per cent of low-income nations.”

[ad_2]

Source link