[ad_1]

Economists warn the strongest period of job creation in recent history cannot be sustained for much longer, as the US central bank is increasingly emboldened to take drastic action to cool the economy and root out high inflation.

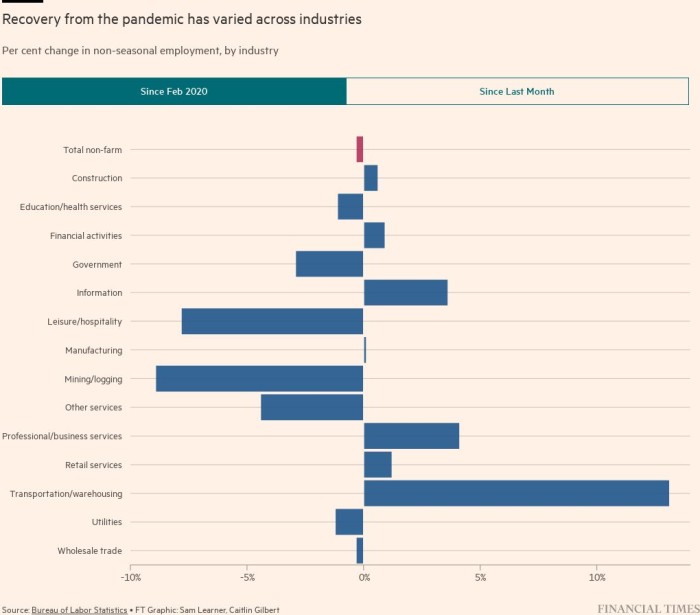

The world’s largest economy added another 372,000 jobs in June, outpacing economists’ expectations by more than 100,000 and underscoring the resilience of the US recovery from the depths of the coronavirus pandemic.

But with the Federal Reserve readying the most forceful campaign to tighten monetary policy since the 1980s — and inclined to be even more aggressive if warranted by the data — those gains are likely to slow significantly.

“You can’t add 372,000 jobs per month forever, because you will be tightening the labour force to extremes,” said Eric Winograd, director of developed market economic research for AllianceBernstein. He reckons a more “sustainable” pace is an average 100,000 positions a month.

“Below that and the labour force is weakening. Above that, it is tightening,” he said.

For most of the pandemic recovery, worker shortages have been the biggest “binding constraint” on the labour market — according to Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Amherst Pierpont — spawning one of the tightest job markets in history. While he expects these dynamics to continue weighing on employment growth, the Fed’s actions to curtail labour demand will soon also begin to take effect.

“There’s good news and bad news in every strong activity number now,” said Andrew Hollenhorst, chief US economist at Citigroup.

“The good news is that you’re further away from recession . . . but the bad news is that there’s more momentum in the economy and more inflationary pressure in the economy, and it may be that much harder for the Fed to slow things down.”

Fed officials have already sharpened their rhetoric about the lengths they are willing to go to ensure inflation does not become entrenched — something they now view as a “significant risk” to the US economy, according to minutes from their June policy meeting.

Consensus is building among top policymakers for a second consecutive 0.75 percentage point interest rate increase at the end of the month, following the first since 1994 in June. That would lift the target range of the federal funds rate to 2.25 per cent to 2.50 per cent.

By year-end, officials are aiming to lift the policy rate to a level that modestly restrains the economy — estimated around 3.5 per cent.

The extent to which the labour market will be harmed as a result is subject to considerable debate. Policymakers are now acknowledging that some economic pain may be necessary and might be less damaging than a situation in which inflation persists at elevated levels for much longer.

Despite these concessions, many officials still maintain that job losses need not be excessive given the historic tightness of the labour market and the near-record number of job openings, which may mean that employers opt to cut back on vacancies as opposed to laying off their staff. Most officials expect the unemployment rate to rise to 4.1 per cent in 2024 — a forecast many economists still view as “wishful thinking”.

“The question of ‘will there be a recession’ is almost irrelevant now,” said Sonal Desai, chief investment officer for fixed income at Franklin Templeton.

“The reality is we’re going to need a slowdown. We need to see wage pressures come down. We need to see some of the froth in the labour market come off.”

Additional reporting by Kate Duguid in New York

[ad_2]

Source link