[ad_1]

Until recently Anne Simpson was considered an evangelical advocate for the cause of environmental, social and governance investing (ESG). This spring, however, the former head of sustainability at the Calpers pension fund, who now runs responsible investing at Franklin Templeton, made a surprising declaration. “I think it’s time for RIP ESG,” she told a conference in New York.

Specifically, she thinks that the war in Ukraine has forced ESG advocates to reconsider some of their approaches, because energy security and poverty reduction have suddenly become as important as the green transition. Box ticking around carbon emissions alone, in other words, does not work.

But does also she think that it is time to jettison any effort to be environmentally “sustainable” altogether, I asked? Absolutely not. “We have to rethink what ESG means,” she argues. “We need a broader, human centred approach.”

The issue at stake is finding the right trade-offs — ways to balance all the different goals around “responsibility” — in the least bad way possible, so as to help as many people as possible thrive on our troubled planet, and prevent catastrophic climate change.

Investors everywhere should take note. Whether or not they love ESG — and are baffled by the current debates swirling around the topic — the idea of responsible investing is far broader and older than the acronym itself. The “values” embedded in your portfolio matter, in both a financial and social sense — and will continue to do so even if analysts are arguing about the finer details of ESG.

The end of an era for ESG?

In the past couple of years, the concept of sustainability and stakeholder-focused business has become wildly — and surprisingly — popular.

That is partly because of the rise of climate activists such as Greta Thunberg, who has managed instil fear into many middle-aged chief executive officers and chief investment officers with her strident campaigns.

However it is also because events such as Covid-19 or the Black Lives Matter campaign have made it hard for corporate boards to ignore social welfare at a time when social media tools and increased digital transparency has made it easier than ever for activist groups to monitor what companies are doing and launch campaigns against them if they breach social norms.

Or to put to another way, the concept of ESG has moved from being a narrow area of activism — driven by people who want to change the world — to a sphere of risk management for corporate boards — where it is shaped by the knowledge that companies which ignore ESG issues can face reputational damage and the loss of customers, investors and employees.

The idea of just focusing on shareholder interests, as the 20th century economist Milton Friedman urged company boards to do, looks increasingly risky — even for those shareholders.

Meanwhile, the amount of money earmarked for ESG funds has exploded — not least because investment groups such as BlackRock argued last year that companies which do not adhere to ESG principles are likely to underperform relative to peers. Thus, while there are numerous different ways of measuring the size of this field, analysts estimate that around a third of all investments are managed with some ESG lens.

However, financial history shows that trends move in pendulum swings: whenever a good innovation catches fire, it typically evolves so fast that it is taken to extremes that cause problems — and an inevitable reaction. And we are now seeing history repeat itself: after a heady boom, a backlash has set in, as some of the problems around the current ESG fashion emerge.

Questions over greenwashing

One trigger for reflection has come from whistleblowers such as Desiree Fixler, a former chief sustainability officer at Deutsche Bank’s asset management arm, who alleged last year that her employer was engaged in widespread greenwashing, claims the company denies.

Another has come from Tariq Fancy, a former sustainability expert at BlackRock, who lashed out against the asset management behemoth, arguing that ESG is actually undermining efforts to curb climate change because it takes the pressure off governments to act — and does not really rechannel capital into green causes as it claims.

Separately, Stuart Kirk, head of sustainable investments at HSBC’s wealth division (who is currently suspended), has argued that the climate risks to investors have been overstated by ESG advocates and central bankers such as Mark Carney, former governor of the Bank of England.

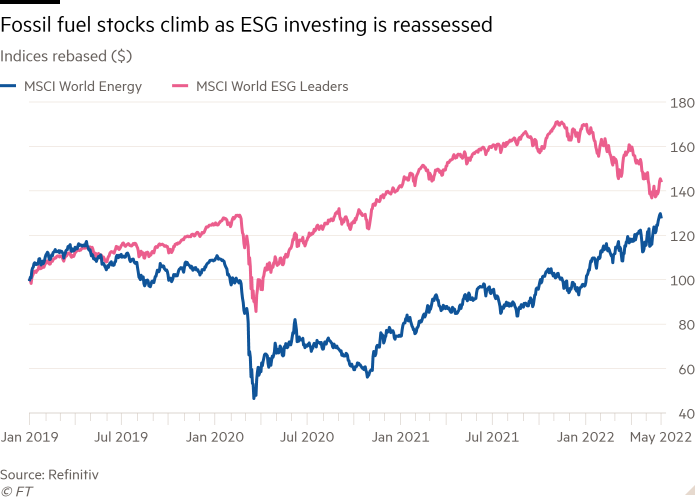

Meanwhile, as Simpson notes, the war in Ukraine has made the issue of energy security so important that some former ESG proponents are starting to recognise that they need to use the hated fossil fuel producers to cope with populations’ needs.

And Russia’s invasion has also highlighted another point: the problems of reconciling “E” with “S” and “G” in a unified way. Some Russian companies, such as En+, which were previously welcomed by ESG activists because they were trying to embrace green technologies, are now being shunned because most ethical investors will no longer buy anything linked to the Russian establishment. The lens of ESG, in other words, has changed. And similar tensions exist around other entities that have nothing to do with the war.

Elon Musk’s Tesla group, say, is often lauded for its high “E” credentials because it created three-quarters of new electric cars in the US last year.

However, the minerals used to make these cars sometimes come from dirty mines, with poor labour conditions, and the company has been criticised for racial discrimination and bad working conditions in its factories. Tesla rejects the claims.

It scores so badly on “S” that the S&P 500 ratings group recently removed Tesla from its ESG bucket, causing its stock price to fall 6 per cent — and Musk to complain that ESG has now become “weaponised by phoney social justice warriors”, and is thus “a scam”.

Rethinking the rules

So does this mean that the impetus behind ESG is dead, or dying? Probably not. Instead, a better way to frame what is going on is that this year’s backlash is a sign that the market is maturing and evolving, in the face of more scrutiny. And this mood of challenge might actually make the idea of “sustainability” more — not less — sustainable and durable as a concept since it could dispel some of the froth.

“I think that what I did [by blowing the whistle on greenwashing] has burst a bubble in a way that will make more credible in the long run,” says Fixler. After all, she points out, in the early years of the 21st century there was another financial innovation craze around credit derivatives, but that boom was not subject to much oversight or challenge until too late; this time round she thinks (or hopes) the challenge is coming so early that it will help counter the excess.

There are several reasons why this might be correct. One is the fact that regulators are already stepping up their own scrutiny. The Securities and Exchanges Commission recently settled with Bank of New York Mellon over allegations that its marketing literature had overstated ESG claims. Other regulators are following suit, and warning that they plan to scrutinise not just the sellside banks — but rating agencies too.

“The whole investment chain has to get involved, and ratings have to be regulated too,” Sacha Sadan, ESG director at the UK’s Financial Conduct Agency, said at an industry event in London last week. “People do get surprised when they see certain stocks [such as oil and gas] in a portfolio that’s an ESG best-in-class . . . and that’s why as a consumer regulator looking after people we have to make sure that is correct.”

As more oversight enters this sphere, a sense of greater precision and clarity is starting to emerge too. That is partly because of a growing recognition that investors need to separate out the “E” from “S” and “G” when they are creating their portfolios and investment strategies; lumping these together in a single rating can cause confusion. But the other factor which is forcing more clarity is a set of reforms that are now emerging in the accounting world.

At the Glasgow COP26 climate change summit, Carney and other financial leaders pledged to create a new consolidated set of accounting standards to measure sustainability, known as the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), an initiative now being led by Emmanuel Faber, former head of Danone, the French foods group.

These rules are likely to emerge in the next couple of years, for both reporting and audit purposes: if companies start presenting their accounts to investors with these metrics, this will inject more clarity too, particularly around the “E” element (which is dramatically easier to measure anyway than S and G.)

The third factor which is likely to give the movement legs, however, is digital transparency. Back in the middle of the 20th century, when Friedman created his vision of shareholder capitalism, it was hard for most investors or ordinary citizens (and even regulators) to know exactly what companies were doing; the only benchmark was the quarterly accounts.

Now, however, outsiders have a vast array of tools with which they can track companies, ranging from social media platforms such as Glassdoor, to satellite services that can monitor emissions — not to mention a host of digital tools that can peer into supply chains.

Equally important, digital technologies have given critics the means to mobilise themselves and publicise their claims in an embarrassing way. The #metoo movements around sexual harassment shows the power of tech in relation to the “S” factor in ESG.

Similar campaigns are emerging around issues such as pollution and carbon emissions. And the power of digital tech has been visibly on display during the Ukraine war too. Most notably, shortly after Russia invaded, Yale University started publishing an index that outlined what companies were doing with their operations in Russia, and giving them grades according to whether they had withdrawn — or not.

The impact was swiftly felt: companies which were earning bad grades started to pull out of Russia, to avoid customer and employee revolts (and the risk of being attacked by the Anonymous hacking groups, which started targeting companies such as Switzerland’s Nestlé that were slow to withdraw.)

A recent survey from public relations group Edelman of public attitudes in the West underscores how digital communication dovetails with this social zeitgeist shift: its poll suggests that “59 per cent of respondents say geopolitics is now a top priority for business, while 47 per cent have bought or boycotted brands based on the parent company’s response to the invasion of Ukraine”. Moreover “nearly everyone surveyed (95 per cent) expects business to act in response to an unprovoked invasion, from applying political and economic pressure to publicly speaking out against the aggressor”.

Of course, a cynic might say that this simply illustrates Musk’s point — namely that ESG has become prone to social media fashions, if not “woke” mob rule, in a way that makes the concept dangerously slippery and hard to define, or apply. It is a fair point: the behaviour of the Russian government was never considered an ESG issue before February 2022, never mind its long-running human rights abuses.

Shifting ties between business and society

However, there is another way to frame what is going on: what the war on Ukraine — and Yale university websites — show is that the relationship of business to society is shifting. When Friedman developed his famous theory of shareholder-first business, he not only lived without digital scrutiny, but also existed in an era (after the second world war) when there was a widespread belief that the tricky problems in society, such as pollution, could be handed over to governments to resolve. The state was seen as being effective. Thus, as the historian Douglas Brinkley points out, when environmental activists such as Rachel Carson embarked on the “Silent Spring” movement in the 1960s, they collaborated with politicians (from both right and left) and labour unions — but not corporate leaders or investors.

Today, however, there is not just a new era of digital transparency, but a collapse of popular faith in the power of governments to fix problems. As a result, companies are being forced into the frame of policy issues, whether their leaders like it or not. And while the issues that corporate leaders are being asked to address seem like an ever-shifting kaleidoscope of problems — ranging from Russia to gender rights to carbon emission to biodiversity — the key point is this: returning to a world where the public thinks companies should “just” chase shareholder returns is unlikely any time soon.

Lessons for retail investors

So what does this mean for ordinary investors who want to embrace sustainability? One key point is to recognise that pursuing ESG strategies is never simple but always requires trade-offs between different “E”, “S” and “G” goals; so much so that, in the future, those three letters are increasingly likely to be separated.

In practical terms, that means that investors who want to “do good” (or at least avoid harm) in the world might need to define their priorities and look for options that let them chase specific goals, such as carbon emissions.

It also means that the companies providing financial services will need to provide more bespoke and customised offerings. Investors and financial service providers alike will need to learn what the new accounting frameworks mean and why they matter. The acronym “ISSB”, for instance, might sound confusing but it could affect asset values in the future, not least because the closely-related “task force for Climate Related Financial Disclosures” framework that is being used as bedrock for ISSB is soon likely to become mandatory for big companies in jurisdictions such as Switzerland, New Zealand and the UK.

Last, but not least, investors need to recognise that while the “ESG” acronym might evolve significantly in the next year — or even be headed for the grave, as Simpson suggests — the concept of responsible investing and business is not likely to disappear any time soon. Companies are under the spotlight more than ever before and investors have increasingly effective tools to force them to change in response to shifting social mores.

Call this, if you like, the rise of stakeholder capitalism — or (as I prefer) a world where lateral vision is needed, rather than narrow tunnel vision. Either way, investors and corporate executives ignore it at their peril.

Gillian Tett is chair of the editorial board, US, and co-founder of FT Moral Money. Follow her at FT.com/moral-money or Twitter @gilliantett, email her at gillian.tett@ft.com

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

[ad_2]

Source link