[ad_1]

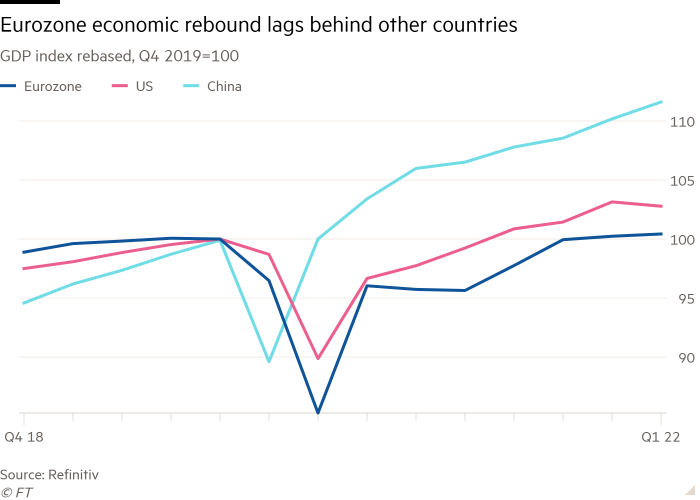

Weaker than expected European growth, a stalling US and concerns about the Chinese economy have raised the prospect of a global downturn driven by surging inflation and the Ukraine war.

New data on Friday showed that the Russian invasion is weighing on Europe’s economy, pushing up energy and food prices, worsening supply bottlenecks for manufacturers as well as sapping business and consumer confidence.

The disappointing news came a day after the US announced that its economy suffered an unexpected 0.4 per cent quarterly contraction, while worries about the impact of severe Covid-19 lockdowns in China caused the steepest monthly fall in the renminbi on record.

The Chinese currency has fallen 4.2 per cent this month to about Rmb6.6 per dollar, the biggest drop since the end of its US dollar peg, which was in place from 1994 to 2005. The fall is greater than a one-off devaluation by the Chinese central bank in 2015 that rattled global markets and a tumble in 2018 during the US-China trade war under the Trump administration.

Economists said the combination of weak global growth, soaring commodity prices and a series of expected interest rate rises by western central banks — including an unusually large 0.5 percentage point hike by the US Federal Reserve that could come next week — would spell trouble for the global economy.

“The world is in really bad shape,” said Erik Nielsen, chief economics adviser at UniCredit. “Particularly in Europe, where we have entered stagflation now.” He predicted that the eurozone was heading for a “double whammy” of an economic downturn and rising borrowing costs as the European Central Bank was likely to raise interest rates as early as July.

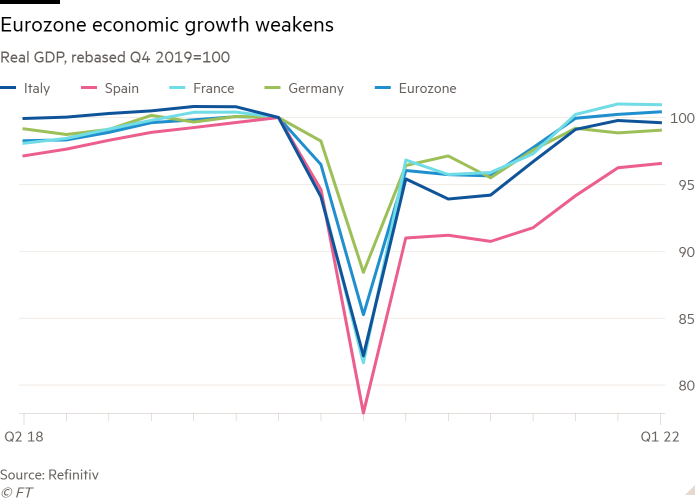

Gross domestic product in the 19 countries that share the euro grew 0.2 per cent in the first three months of the year, compared with 0.3 per cent in the previous quarter, Eurostat said on Friday. Economists polled by Reuters had on average forecast growth in the bloc to remain stable.

France’s economy stagnated in the first quarter, while Italian output contracted. The Spanish economy also lost pace. Germany was the only one of the four biggest EU economies to beat expectations, as it posted meagre growth of 0.2 per cent from the previous three months.

“We are seeing peak stagflationary fears now and this is giving us a reality check on the real costs of the war,” said Ludovic Subran, chief economist at Allianz, adding that he feared a “recessionary tightening” of monetary policy by the ECB in the coming months.

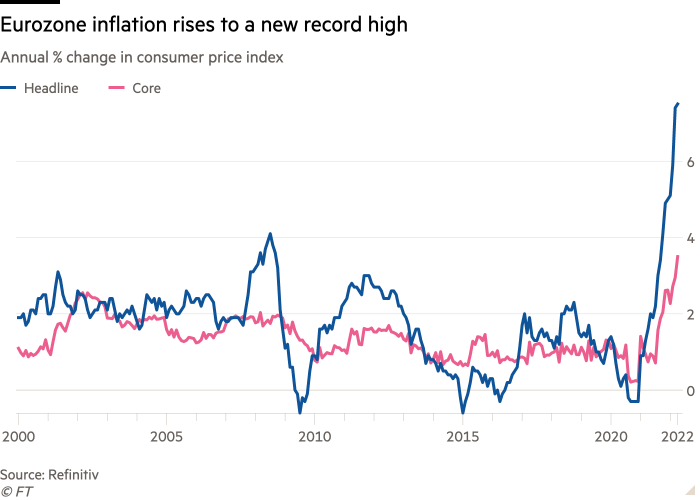

Inflation in the eurozone was 7.5 per cent in the year to April, up from a record high of 7.4 per cent in the previous month. Energy prices rose 38 per cent, while unprocessed food prices jumped 9.2 per cent. Core inflation, excluding energy and fuel, increased to 3.5 per cent from 2.9 per cent.

The data show price pressures continuing to build in the eurozone, lifting inflation further above the ECB’s 2 per cent target and triggering calls for it to accelerate the reversal of ultra-loose monetary policy.

“For the ECB, the continued — albeit slowing — economic growth means that it is likely to act sooner rather than later,” said Bert Colijn, an economist at ING. He forecasted that the central bank could raise interest rates in July if the economic outlook does not worsen, while adding “that’s a big if”.

Philip Lane, chief economist at the ECB, said on Friday there was “still a lot of momentum in the recovery”. He said the depreciation of the euro, which this week hit a new five-year low against the dollar, would push up the central bank’s next inflation forecasts due in June. “Inflation is very high and that does carry its own risk of momentum,” he told Bloomberg.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has clouded the outlook for European economies. Economists are concerned that an escalation of western sanctions on Moscow risks leading to shortages of oil and gas that would hit industry hard and send energy prices even higher, eroding household income and further denting consumer and business confidence. Russia has already cut off gas supplies to Poland and Bulgaria.

Soaring consumer prices, continued pandemic restrictions and the fallout from the Ukraine war all took their toll on economic activity in the first three months of this year. Italy’s economy was the worst performer, shrinking 0.2 per cent, while Spain’s growth slowed the most to 0.3 per cent. The strongest performers were Portugal and Austria, where output expanded by 2.6 and 2.5 per cent respectively.

Germany’s 0.2 per cent rise in first-quarter GDP marked a rebound from a 0.3 per cent contraction in the previous quarter, meaning Europe’s largest economy avoided a technical recession, defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth.

[ad_2]

Source link