[ad_1]

When Kate Daly, a mother of two from London, went through a bitter “train wreck” of a divorce 10 years ago, she estimated the painful process cost her £80,000 in legal fees.

“There was so much hurt and acrimony,” says Daly, a former KPMG change consultant who later trained as a counsellor and divorce coach. “We had two separate solicitors and spent tens of thousands of pounds on legal fees. I came out of the process really bruised.”

The stressful situation was exacerbated by the divorce system, which forced most estranged couples to apportion “blame” for their breakdown in order to part ways.

“It was a really pointless system and added unnecessary stress . . . the requirement that you should stand up and tell the state why the marriage has broken down. Why is it the state’s business?” says Daly who, after her own difficult experience co-founded Amicable, an online divorce service.

Ending the “blame game” is the main objective of the long-awaited shake-up of divorce laws in England and Wales which came into effect this week, allowing couples to part without holding one party accountable for the breakdown of the marriage.

Dominic Raab, the justice secretary, said: “We want to reduce the acrimony couples endure and end the anguish that children suffer. That’s why we are allowing couples to apply for divorce without having to prove fault . . . enabling couples to move on with their lives without the bitter wrangling of an adversarial divorce process.”

Under the old system, a combative start to a divorce put some couples on a path to higher legal costs by triggering conflict at the outset. This could eat away at their financial resources — and the pool of assets they eventually agreed to split.

“Often when discussing behaviour to put in a petition it can spiral into a very unpleasant start to the case,” says Helena French, associate in the family team at law firm Russell-Cooke.

The divorce, dissolution and separation bill was passed in June 2020, but came into law only on April 6 after delays for IT updates to the online divorce system and changes to court procedure. It allows couples to cite the irretrievable breakdown of a marriage as their sole basis for divorce, without the need for further justification or detail.

Faults and feuds

Fault and blame has been embedded in the divorce system in England and Wales since the 1973 Matrimonial Causes Act, which was itself born of a long history of fault-based divorce dating back to the 1660s.

When justifying the irretrievable breakdown of their marriage, spouses had to choose between adultery, “unreasonable behaviour”, desertion of two years, two years’ separation with consent or five years’ separation. So anyone seeking a divorce in less than two years had to cite adultery, behaviour or desertion.

In practice, the system often led estranged couples to get off on the wrong foot as they argued over this selection before the discussion of knottier subjects such as finances or child arrangements had even begun.

“A lot of people don’t realise they have to put down problematic behaviour [on the form],” says Liz Trinder, professor of socio-legal studies at Exeter University and co-author of a 2017 academic report on divorce law.

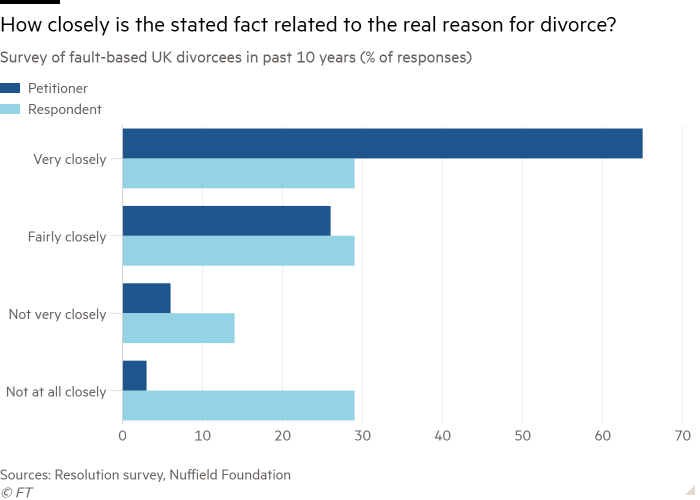

The divorce petition citing behaviour had become a “completely meaningless ritual”, she says, with divorce petitions often drafted to include anodyne evidence designed not to upset the other spouse but merely to satisfy a court that a marriage had broken down.

“People might look online and cut and paste something. Someone saying that their spouse spent too much time at work and this made them feel neglected is a classic example,” Trinder says, adding that forcing couples to find fault “caused unnecessary conflict and needless pain”, particularly for their children.

Phoebe Turner, a managing partner at Stowe Family Law, says stock phrases include “we no longer socialise together”, “we no longer share a bed” or “we no longer spend time as a family”.

“You do not have to put in specifics. People keep them quite anodyne so they are enough to show the judge the marriage has broken down. If someone just said ‘We don’t get on very well,’ then the judge might say that is not enough.”

In the past adultery was more commonly used as a ground for divorce. In the 1930s, “hotel adulteries” were staged, where the respondent in a divorce — usually the man — arranged to be seen in bed with a supposed female partner who had in fact been paid to play the role.

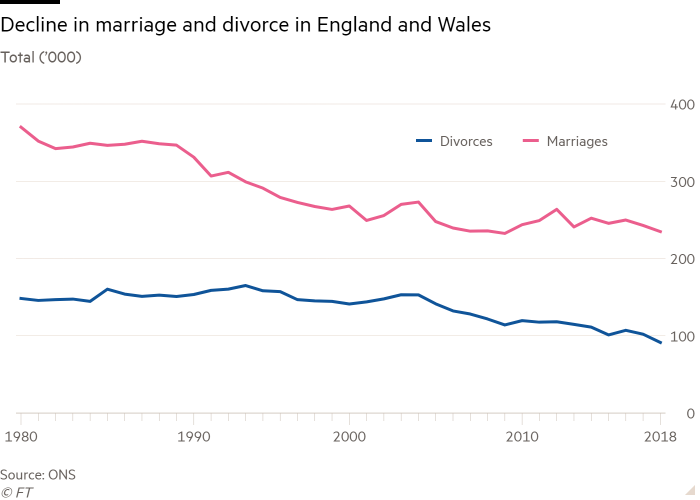

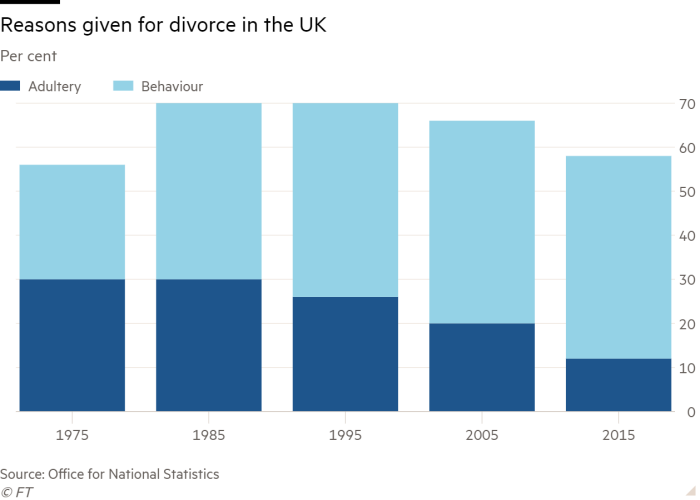

Trinder’s research showed a gradual decline in use of “adultery” in petitions from 30 per cent to 12 per cent of divorces between 1975 and 2015 and the corresponding increase in “unreasonable behaviour”, from 26 per cent to 46 per cent of all divorces over the same period. One reason that adultery has faded as a cause, she suggests, is because it requires an admission from the respondent, unlike unreasonable behaviour.

The divorce system in other countries shows another path is possible. Sixty per cent of English and Welsh divorces in 2015 were granted on adultery or behaviour grounds, the report found. But the figure was 6 per cent in Scotland, which has a different legal system; 5 per cent in New York state; 1 per cent in Italy; and 0.2 per cent in Norway. Divorce is generally a quicker process in these jurisdictions, so the requirement to assign blame was dropped.

The new legislation eliminates the possibility of one party “refusing” a divorce. Previously if one spouse declined to give consent, the unhappy couple were condemned to live separately for five years before they could legally split. One example was the case of Tini Owens from Worcestershire, who brought a high-profile divorce fight to the Supreme Court in 2018 at the age of 68.

Owens protested that her estranged husband Hugh, now in his 80s, had contested her petition after 40 years of marriage, saying he thought they had a “few years” left to enjoy together. The judges sympathised with Owens but said they could do nothing to help until the law was changed.

This week she welcomed the introduction of no-fault divorce. “No one should have to remain in a loveless marriage or endure a long, drawn out and expensive court battle to end it,” she said in a statement.

As a result of the reforms, divorcing couples should find it easier — and less expensive — to file an online divorce form themselves without the need for a lawyer. “It will certainly make it smoother,” says French.

It means any legal fees can be targeted on sorting out a financial settlement — for example splitting pensions or dividing assets — or dealing with any childcare arrangements. A court order may be needed to finalise finances, for example.

Money saving potential

The changes could benefit legal services firms like Daly’s Amicable, which she set up with Pip Wilson, a tech entrepreneur. The company offers individuals or divorcing couples a fixed price divorce service — ranging from £300 for a simple divorce to £6,690 to deal with divorce, child welfare and finances.

Heading to the divorce courts is typically far more expensive. In 2012 research by Novitas estimated that legal costs were £40,000 per person on average in London and £13,000 outside the capital. The average cost of a UK divorce last year was £14,561, according to estimates by Aviva.

“All that money could be spent on an extra bedroom or a bigger garden or school fees,” Daly says.

It took two years for Alison (not her real name) to finalise her divorce, after filing for a split on adultery grounds. She says the new legislation will make things “a bit easier” but is no panacea. “It is a minor hurdle at the beginning before the real show begins and you start fighting over money and children. The legal fees spiral out of control. My other half’s lawyer was fuelling him and he couldn’t see it.”

Couples who save money at the start as a result of the changes are likely to benefit from having extra resources later on to secure an agreement on finances. Kate Landells, partner at law firm Withers, says: “Drafting a court order is beyond most people . . . It’s like doing conveyancing for your own house sale. [But] if you want to make sure some line is drawn under it, an order is the best way of doing that.”

Without a court order, one spouse can come back to court years later if their ex-partner comes into wealth. Unlike the civil courts, the family courts have no time limit for claims to be brought.

Dale Vince, a green energy entrepreneur, faced a claim in 2015 after his ex-wife Kathleen Wyatt came to court. Eventually she received a £300,000 share of Vince’s fortune — 23 years after they divorced.

There is some evidence that many couples have waited until after April 6 to divorce to avoid unnecessary acrimony and causing stress to their children. But others have also rushed to get their divorce through the old system, either because they have already started the process or because they want the reasons that their marriage has failed to be officially documented.

“You have to understand catharsis is important for some clients if they feel their spouse has not listened to what they were saying,” says Landells.

Overall, though, the changes should be positive, both psychologically and financially. “It will take out the conflict caused by the divorce process in the justice system,” says Trinder. “In some ways it’s a modest change — in other ways it’s a fundamental one where the system is treating people as adults — they are the ones who know why their relationship has broken down.”

[ad_2]

Source link