[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Warren Buffett bought a big conglomerate in cash on Monday. Berkshire Hathaway’s having a moment, and it seems Buffett is keen on keeping the momentum going. Bond markets have momentum too — in the wrong direction. More on that below. Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

The yield curve is scaring everyone

Last week Ethan wrote that the horrific performance of US Treasuries was something of an inevitable return to normal after they were placed into a policy-induced economic coma during Covid:

Across the curve, Treasury yields are returning to their pre-pandemic levels — even if in fits and starts. Even the stubborn 30-year yield is back where it was in early 2019 . . . Epic fiscal, monetary and epidemiological interventions transformed the US economy overnight. A bear market in Treasuries mostly represents things returning to normal, though high inflation and Russia’s war have made for a bumpier ride.

This remains true, but the ride has only become rockier in the past few days. As the FT markets team reported on Monday, Treasuries have now had their worst month since 2016. Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell exacerbated the sell-off with a hawkish speech, in which he left open the possibility of 50 basis points rate increases in the coming months. All the same: the 10-year yield is only where it was in mid-2019. Welcome back, everyone.

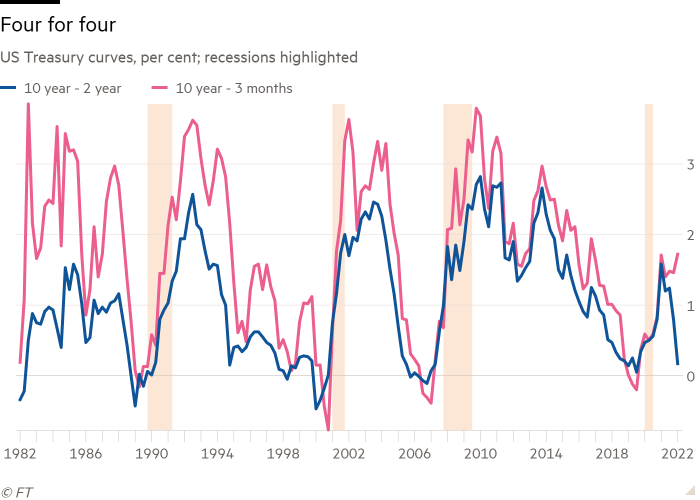

The worry is that returning to normal at the same time the Fed digs in for a fight against inflation might trigger a recession. That, at any rate, is the worry being flagged by the yield curve. Powell’s speech triggered a lively, 18-basis point rally in the two-year Treasury; the 10-year moved up by less than half as much; leaving the difference between the two at a measly 19bp. This left everyone staring grimly at a chart like this one:

The blue line, the 10-year/2-year curve, is barrelling straight towards zero. In the past 40 years, every time that has happened, a recession has followed (as the shaded bits of the chart show). In fact, it’s worse than that: inverted 10/2 curves have preceded the last eight recessions and 10 out of the last 13 recessions, according to Bank of America.

Why? David Kelly, chief strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, sums it up pithily:

An inverted yield curve doesn’t do much to the economy, but it’s a very bad sign. The only reason you’d buy a long-term bond at a lower yield than a short-term one was if you thought yields were going to fall . . . this usually happens when most people think the Fed has gone too far or will go too far.

That’s the classic “Fed mistake”. Kelly frames the current case for a Fed mistake in terms of the historically low unemployment rate. The economy has to slow somewhat in the not-too-distant future, because at 3.8 per cent unemployment, “we’re out of workers”. “It’s hard to produce more when there is no one to produce it,” he says. This might happen just as the US central bank pushes rates to their peak, exaggerating the slowdown to the point of recession.

So the Fed risks causing a recession and then having to rush to correct its mistake. John Higgins of Capital Economics lays out what the swerving policy pattern looks like:

In the past, the 10-year yield itself fell significantly after the 10-year/2-year and 10-year/3-month spreads fell to, or below, zero . . . this coincided with a ‘bull steepening’ of the curve, as the Fed subsequently eased policy to counteract the onset of an economic downturn.

But the Fed’s easing comes too late, markets take the first hit, and the economy follows. Here is Bank of America’s technical analyst Stephen Suttmeier on how it plays out:

While the lead times vary and can be long, the typical pattern is that the 2s/10s yield curve inverts, the S&P 500 tops sometime after the curve inverts and the US economy goes into recession six to seven months after the S&P 500 peaks . . . post-inversion dips and last gasp rallies for the S&P 500 . . . often occur prior to the deeper recession-linked market corrections.

Markets can do quite well in and around curve inversions, as this excellent table of sector performance from Strategas’ Ryan Grabinski highlights:

Tech leads heading into an inversion. Classic defensives such as utilities, healthcare and consumer staples do well afterwards, as investors gird for what is to come. But remember: when the recession does eventually hit, it’s just awful. Suttmeier calculates that during the average recession, the S&P 500 drops by a third over 13 months — enough to make anyone think twice about hanging on for that last bounce after the curve inverts.

This is all pretty dreary, and explains why, if the 10/2 does invert, people will freak out a bit. There are, however, a few rays of sunshine visible, if you are willing to squint a bit.

This first ray is the 10-year/3-month curve, which interest rate nerds like to point out has been shown to have superior recession-predicting power than the 10/2. Powell referred to this in his speech on Monday. Here he is, as quoted by Bloomberg speaking at the National Association for Business Economics:

There’s good research by staff in the Federal Reserve system that really says to look at the short — the first 18 months — of the yield curve. That’s really what has 100 per cent of the explanatory power of the yield curve. It makes sense. Because if it’s inverted, that means the Fed’s going to cut, which means the economy is weak.

Looking at the 10/3 month curve in the first chart up above, you will notice it is not nearly inverted (here is some of the research Powell is referring to), a very different message from the 10/2. Capital Economics contrasts the probability of recession predicted by the 10/2 and the 10/3 month, using a model similar to one the Fed itself uses:

So even if the 10/2 inverts, we might be able to dodge the recessionary bullet? Ethan Harris, of the Bank of America economics team, argues that we can. He thinks what the yield curve is telling us has changed over the years.

Harris points out that long bond yields are made up of two parts: the sum of projected short-term rates, and then a premium on top of the sum, to compensate investors for locking up their money. But this latter part, the “term premium”, has been squeezed out of the market by central bank quantitative easing:

The 10-year term premium has averaged about 1.5 per cent over the postwar period. Hence, in the past it took a very tight Fed and high fears of recession to trigger a yield curve inversion. Specifically, the market had to expect the future funds rate to average 150bp below the current funds rate to invert. The Fed only cuts that much in a recession. No wonder inversion was a good predictor of recessions.

Today, the long end of the US yield curve is heavily distorted. The Fed has deliberately driven down the long end of the yield curve with its asset buying programme. At the same time, very low bond yields outside the US exert downward pressure on US yields. The upshot is that the term premium has now dropped into negative territory. The yield curve can now invert even if the market expects no rate cuts from the Fed.

Here is Harris’ chart of the term premium. The change has been dramatic:

This makes perfect sense to me. But to say arguments like Powell’s and Harris’ are met with cynicism by crusty old Wall Streeters is an understatement. As our friend Ed Al-Hussainy of Columbia Threadneedle put it:

Every time the 10/2 curve inverts, market participants come out with a long list of reasons why the curve’s slope tells us little about the current environment and should have no correlation with a recession. We all know what happens subsequently.

For the past half century or so, what happens subsequently is a recession.

One good read

Fintech has been the new hotness for awhile. But rising rates could make boring old banks cool again.

[ad_2]

Source link