[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. I’m on vacation again next week (I find late winter very depressing so I pack in the holidays). You will be in Ethan’s capable hands once again. He will publish letters next Tuesday and Friday. On the other days, we think you should read Due Diligence, the FT’s newsletter about deals and dealmakers. It is good. Sign up here. Email Ethan at ethan.wu@ft.com with ideas, encouragement and complaints. Don’t email me. I’ll be fishing and won’t answer.

Berkshire as inflation play

Shares in Berkshire Hathaway are having a really, really good 2022:

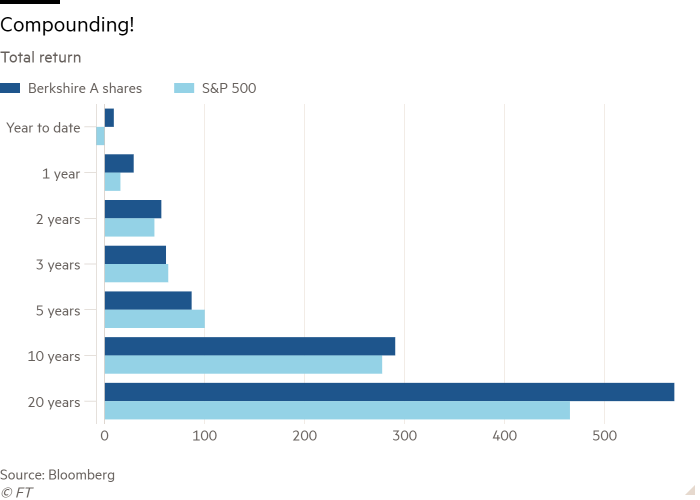

This surprises me, because Warren Buffett’s holding company/cult had not been doing so well the last time I checked in, back before the pandemic. For the 10 years up to the end of January 2020, Berkshire returned 194 per cent; the S&P 500, 275 per cent. This is not that surprising. Berkshire is a sort of index itself, but its only exposure to big tech is through its big position in Apple. Without exposure to Amazon, Microsoft, Tesla and the rest, it’s hard to see how the “Berkshire index” could beat the S&P.

And indeed, Buffett himself shares the view that it is unlikely that, over any sufficiently long period, Berkshire can beat the S&P. Here’s an excerpt from an interview that I did with him a few years ago, along with my colleagues Eric Platt and Oliver Ralph:

At the outset [of the interview] he was asked which would be the better investment to put in a child’s account — a share in Berkshire, or a share in the S&P? He did not hesitate: “I think the financial result would be very close to the same.”

. . . asked if his expectation of “modest” outperformance against the market has changed [since he first stated it 20 years ago] he adjusts his forecast by a single word: “very modest”. “I think this: if you want to join something that may have a tiny expectation of better [performance] than the S&P, I think we may be about the safest.” Surely, greater safety, over the cycle, will translate to higher returns? He doesn’t bite: “If we got lucky,” he says.

Certainly the past 20 years bear out the idea that there are structural reasons Berkshire cannot outperform.

What is interesting here is that all of the 10-year outperformance of Berkshire versus the S&P has occurred this year. The two-decade outperformance of Berkshire is more impressive (570 per cent versus 465 per cent). It amounts to annual outperformance of one percentage point, plus the magic of compounding.

If Berkshire can, over the long run, give you an extra percentage point of performance a year, then it’s a nice thing to own. All you have to do is buy the stock. You don’t have to pay some clever hedge fund manager 2 and 20 for the privilege of the mild outperformance, and the performance is pretty stable. You can sleep at night owning it.

But the stonking outperformance so far this year suggests that Berkshire might offer something more than “very modest” outperformance in a changing market environment. The bull case is that Berkshire is focused on businesses that were out of favour in the tech-dominated, low-inflation era that just ended, and may be much more appealing as big tech’s valuations cool and inflation digs in.

Berkshire has roughly double the exposure to energy and utilities that the S&P has. Its railroad business (perhaps 15 per cent of the company’s value) is a pseudo-monopoly with terrific pricing power. The manufacturing and retail businesses that Berkshire have bought over the years have been chosen in part for pricing power, too (what Buffett likes to call their “moats”). It has big positions in bank stocks, which will benefit from higher rates. And beyond the whopping stake in Apple, there’s almost no tech exposure.

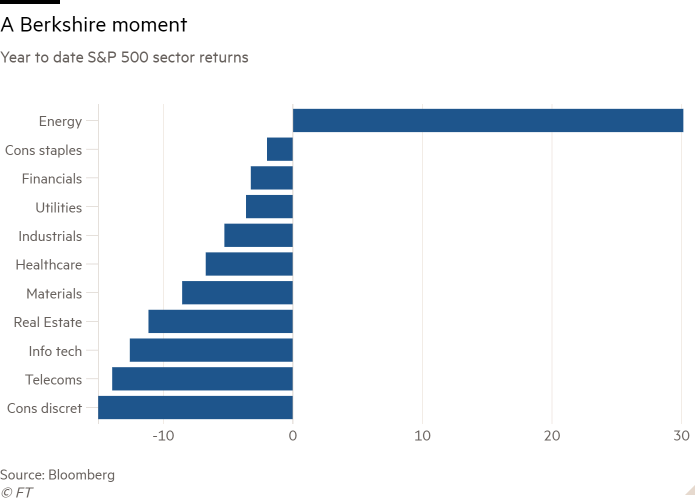

So far this year, this combination has worked perfectly. Here are S&P 500 returns by sector:

Obviously, the wild outperformance of energy shares are the big story here, but the five top-performing sectors are basically a laundry list of Berkshire’s heaviest exposures. Even in consumer staples, where Berkshire does not specialise, its stakes in Coke and Kraft Heinz (worth $37bn together) account for perhaps 5 per cent of the group’s value.

I asked the analyst Meyer Shields, who covers Berkshire for KBW, about my thesis that Berkshire was well positioned for an inflationary environment. He agreed, noting that the energy exposure is far and away the most important explanation for the recent outperformance. He also noted that while the insurance industry (a huge Berkshire exposure) often struggles to keep pace with inflation, pricing in the industry has been strong recently, and shows no signs of softening.

He also pointed out another important factor that had not occurred to me — what the wobbly wider market means for Berkshire’s cash pile, which has been a drag on performance. “If you see the wider indices going south, and things becoming less frothy, maybe there is something to do with $150bn,” namely an accretive acquisition, he said.

I’m still not totally convinced that any of this is a formula for sustained outperformance, even to the modest degree we have seen over the past two decades. With a market cap of three-quarters of a trillion dollars, it just doesn’t make sense to me that Berkshire can do better than a diversified large-cap index over time. But there could be multiyear periods in which Berkshire beats the index, if conditions favour its chosen exposures. There is some reason to think we might be entering such a period now. That said, calling big market cycles — when they have begun and how long they will last — is hard.

One good read

Western sanctions on Russia are making money look political. Harold James and Brendan Greeley argue in FT Alphaville that this shouldn’t surprise us. Money, they write, “is a series of agreements and customs among and within countries. Violating some of those agreements can shatter the rest, destroying the privilege of money.”

[ad_2]

Source link