[ad_1]

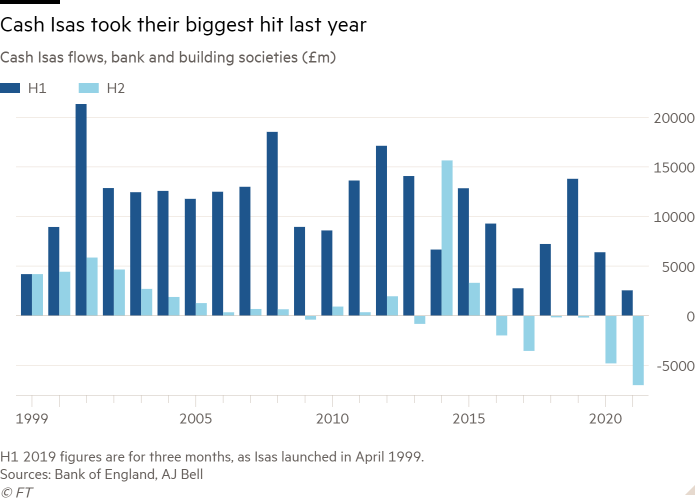

UK savers pulled a record amount of money out of cash Isas in the second half of last year, as low interest rates and mounting living costs dimmed the products’ appeal.

Savers took out more than £7bn from cash Isas in the six months to December — the biggest half-year withdrawal since they were launched 23 years ago — according to research published this week by investment broker AJ Bell.

“Poor interest rates, the cost of living crunch and the dwindling appeal of cash Isas have all played into these outflows,” said Laura Suter, head of personal finance at AJ Bell.

The surge in withdrawals highlights the dilemma facing savers. As the end of the tax year looms, they must choose between holding cash, despite inflation reaching a 30-year high, or investing it in volatile markets.

Sarah Coles, senior personal finance analyst at broker Hargreaves Lansdown, said the outflows could partly be explained by the way people use Isas. Typically, they open accounts in March or April, just before or after the start of the new tax year, and withdraw money from them “as they get to expensive times like holidays and Christmas”.

The pandemic exacerbated the trend, she added. Millions of people amassed savings during lockdowns, but the reopening of the economy in the second half of 2021 gave them new opportunities to spend.

“Wealthier households who are more comfortably off may also be using their spare cash to splurge after two years of the pandemic, booking a pricier holiday or treating their family after so long in various lockdowns,” said AJ Bell’s Suter.

The appetite to save nonetheless remains strong, according to the same research, which shows savers put £35.5bn into non-Isa cash accounts over the same period.

Persistently low interest rates have blighted demand for cash Isas. This is partly due to “how slow the big banks have been to pass on rate rises into their Isas” in light of spiking inflation, said Coles. Appetite for the products was also blunted by the government’s decision in 2016 to create a personal savings allowance, which meant most savers would pay no tax on interest from their non-Isa cash pots.

Interest rates on cash Isas averaged 0.3 per cent at the end of last year, according to AJ Bell’s research, which analysed Bank of England data since 1999, when Isas were launched. This is less than a third of pre-pandemic rates, which averaged at 1.4 per cent in 2019.

A saver putting £20,000 into a cash Isa at an interest rate of 0.3 per cent for 10 years would end up with £16,849 in today’s money, assuming an annual 2 per cent rate of inflation. If inflation were 3 per cent over the decade, the purchasing power of the savings pot would fall to £15,211. Official figures put CPI inflation in the 12 months to January at 5.5 per cent.

Those with larger sums to invest are more likely to opt for a stocks and shares Isa than keep their money in cash. Last year, transfers from cash to stocks and shares Isas at Hargreaves Lansdown were up 30 per cent from the previous year. “The tipping point comes at around £30,000, when people become more likely to open a stocks and shares Isa,” said Coles.

Stock investments are likely to produce a better return, said Andrew Hagger, founder of consumer website Moneycomms.co.uk, but the two Isa products were “like chalk and cheese”.

While cash is “very simple with no risk”, stocks and shares Isas are “more medium to long-term products,” said Hagger. And while there are “no charges to worry about” with cash, stocks and shares products can come with fees.

Investors considering stocks could also be put off by the recent volatility of the stock market, with tech sell-offs in the US and European equities swinging ahead of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

According to finance website Moneyfacts, the average stocks and shares Isa returned 6.92 per cent between February 2021 and February 2022, while the average cash Isa returned 0.51 per cent — a record low — over the same period.

Higher earners or those with more assets may be able to sit on their savings or invest, but the cost of living crunch means that those earning less are more likely to spend from their cash Isa savings.

“Many households will have no spare money each month, or will be dipping into savings” as wages fail to rise by as much as living costs, said Suter.

[ad_2]

Source link