[ad_1]

The pandemic’s housing boom has been welcome news for homeowners hankering for a house in the country and estate agents dreaming of a holiday in Dubai. But for those looking to buy their first home, it made an already daunting task much harder, forcing many either to move back in with their parents or continue shelling out large sums of money in rent.

The immediate pressures of the pandemic may have eased — and first-time buyer numbers are increasing again — but the threat of higher interest rates and the looming cost-of-living crisis suggest that even more difficult times lay ahead.

During the pandemic, affording a deposit — the main hurdle that first-timers have faced for at least a decade — got harder. Since the end of the financial crisis, low interest rates may have kept prospective buyers’ mortgage repayments down, but they have also boosted house prices, steadily upping the amount of cash needed as a downpayment. Then, when Covid struck, the goalposts shifted.

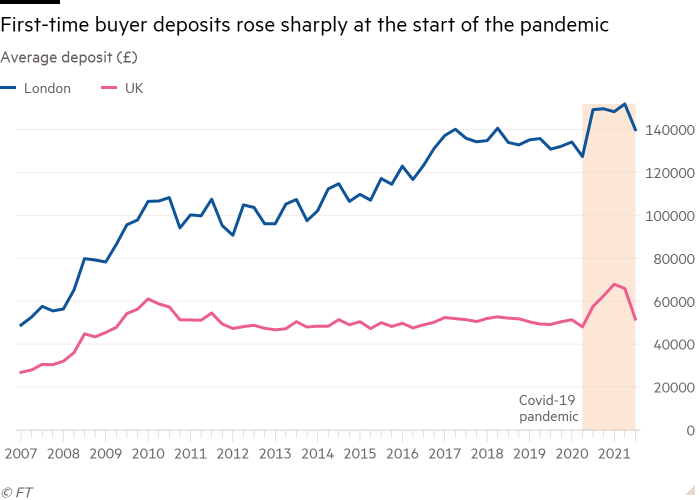

In 2019, the average first-time buyer deposit in the UK was £49,800. A year into the pandemic, in the first quarter of 2021, the average deposit peaked at £67,800, a rise of more than a third — meaning buyers had to find, on average, another £18,000 from somewhere.

Help from the Bank of Mum and Dad was important, especially in London, where the average first-time buyer deposit peaked at over £151,700 in mid-2021, and where only those born to an extremely well-capitalised bank could afford to buy.

Deposits rose both because house prices boomed — up more than 16 per cent since the start of the pandemic and counting, according to building society Nationwide — and because first-time buyers have had to deal with a credit crunch.

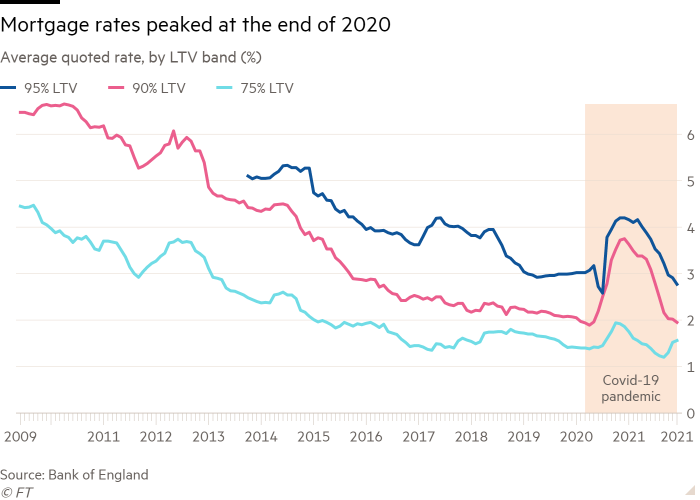

In 2020, despite rising prices and transactions, there was still widespread concern about how the housing market would be affected when the stamp duty holiday came to an end and government support for the economy was eased. Mortgage lenders reacted to this uncertainty by cutting back on their riskiest lending.

The volume of mortgage lending with loan-to-value (LTV) ratios between 90 and 95 per cent collapsed. Data from Moneyfacts shows the number of mortgage products at 90 per cent LTV fell from 779 in March 2020 to just 62 by September.

And even if you were lucky enough to get one of the few high-LTV mortgages available, you would have to pay much more for the privilege. The average quoted rate on a 90 per cent LTV mortgage rose from 1.9 per cent in March 2020 to 3.8 per cent in December 2020.

Both the cost and availability of higher-LTV mortgages have returned to pre-pandemic levels thanks, in part, to a government scheme announced during the Budget last March: the Mortgage Guarantee Scheme. Largely a repeat of the original Help-to-Buy scheme launched in 2013, the policy offers compensation to lenders if they repossess homes in negative equity.

While initial data on the number of mortgages supported by the scheme has been low — just 812 completions in the first three months — its primary role was to reassure mortgage lenders by the government taking a stake in the housing market.

And it appears to be working: with more and cheaper mortgage products at higher LTVs, first-time buyer numbers have increased. But the balance of the market has clearly shifted and is being dominated by home-movers for the first time in years.

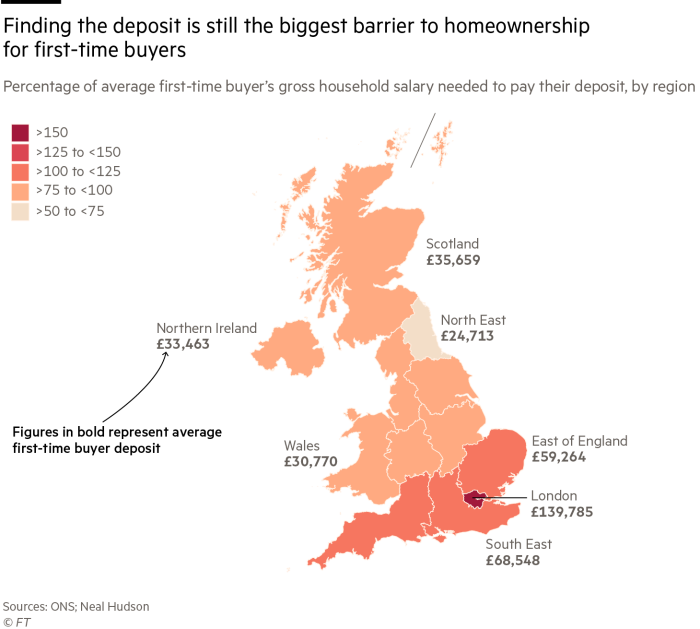

While the immediate pressures of last year’s credit crunch may have eased, record high house prices keep the barriers to home ownership high. Data following the end of the credit crunch shows successful first-time buyers need sizeable deposits relative to their household salaries — ranging from 64 per cent in the North East, the most affordable part of the country, to 165 per cent in London.

First-time buyer salaries are significantly higher than average because first-timers already tend to be higher earners than their peers stuck in the private rented sector.

Further challenges lie ahead. Aside from record house prices, the rising cost of living is squeezing household finances and some mortgage lenders are tightening affordability lending criteria. At the same time, rents are rising rapidly again — up 8.3 per cent in 2021, according to Homelet — making it even more difficult to save a deposit.

While raising interest rates might offer some respite from endless price rises, first-time buyers hoping for a price crash ought to be careful what they wish for: crashes tend to just help cash-rich buyers and investors rather than mortgage-dependent first-timers.

After the crash of 2007-08, for example, when the average property price fell 23 per cent, the number of first-time buyer mortgaged purchases fell from a monthly average of 33,406 in 2006 to 16,162 in 2009, according to UK Finance. No month recorded more than 30,000 mortgaged first-time buyer transactions again until mid-2016.

When the Bank of England reviews its mortgage affordability stress test — due in the first half of the year — it might decide to loosen the criteria and help some first-time buyers make their purchase sooner.

However, the fundamental unaffordability of house prices relative to incomes and the absence of very high LTV mortgages — 95 per cent-plus lending has not recovered from the financial crisis — will ensure that large numbers of people continue to struggle to buy their own home. The challenge for the Bank of England is the more they help first-time buyers, the greater the risk of it all going badly in a crash.

Government policymakers may be rather distracted at the minute, but if they want to help more first-time buyers host a party in their own garden, they need to do more to lower the deposit hurdle while also easing the rising cost of living for renters.

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first

[ad_2]

Source link