[ad_1]

How are we to assess the outcome of COP26 in Glasgow? It would be reasonable to conclude that it was both triumph and disaster — triumph, in that some notable steps forward have been taken, and disaster, in that they fall far short of what is needed. It remains very doubtful whether our divided world can muster the will to tackle this challenge in the time left before the damage becomes unmanageable.

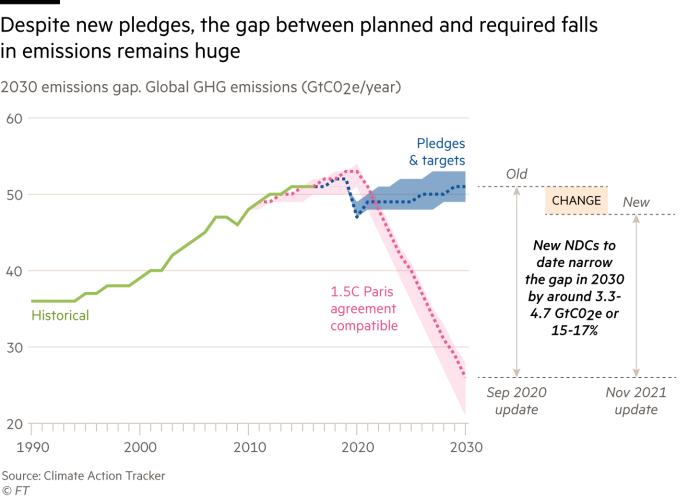

Climate Action Tracker has provided a helpful summary of where we are: on current policies and actions, the world is set for a median increase in temperature of 2.7C above pre-industrial levels; with the targets for 2030 alone, this would fall to 2.4C; Full implementation of all submitted and binding targets would deliver 2.1C; and, finally, implementation of all announced targets would deliver 1.8C. Thus, if the world delivered everything it now indicates we would be close to the recommended ceiling of a rise of 1.5C. (See charts.)

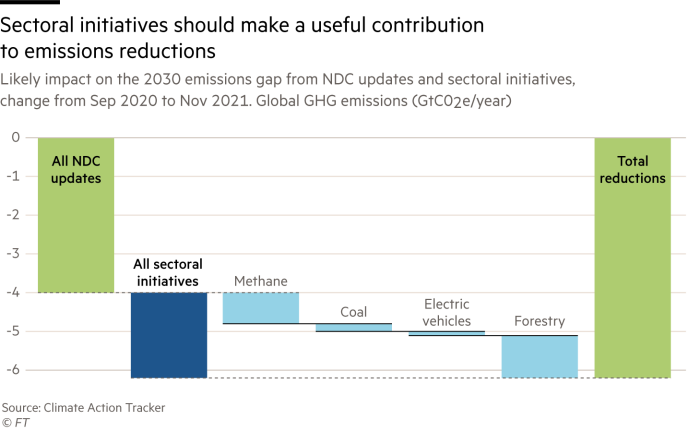

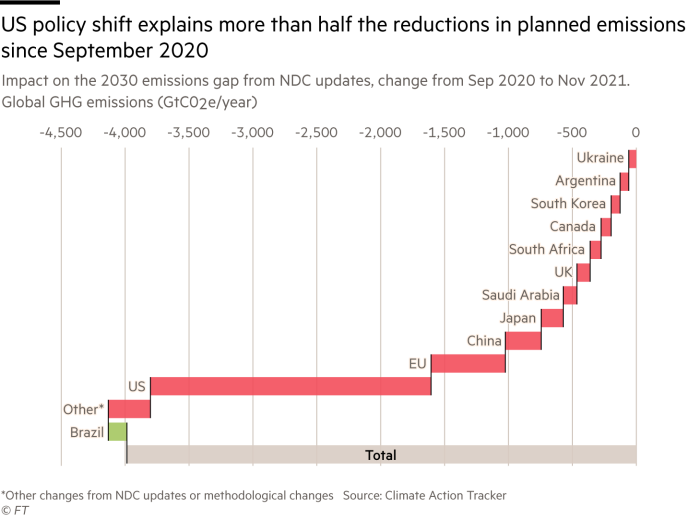

Scepticism is fully justified. According to Climate Action Tracker, only the EU, UK, Chile and Costa Rica now have adequately designed net zero targets. Announced improvements in nationally determined contributions (NDCs) since September 2020 will lower the shortfall in the reductions in emissions of greenhouse gases required by 2030 by just 15-17 per cent. More than half of this reduction in NDCs comes from the US, whose future policies are, to put it mildly, uncertain. New sectoral initiatives will lower 2020’s shortfall in the reductions in emissions of greenhouse gases by 2030 by 24-25 per cent. Announced reductions in methane emissions and deforestation would be particularly significant, if delivered. But the reduction in deforestation is doubtful. In any case, the shortfall stays large.

Nevertheless, the picture is not entirely bleak. Net zero commitments now cover 80 per cent of total emissions. The 1.5C ceiling is also a clear consensus. Another good signal is a joint declaration between the US and China, since nothing can be achieved without these two countries. The final declaration also includes a commitment to “accelerating efforts towards the phase-down of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”. This is far too little. But it is a first in climate agreements.

Yet, if the world is to make the recommended reductions in emissions by 2030, much more needs to happen. One possibility is new commitments in the follow-up COP, which will be in Egypt next year. This is to be the first of a series of annual high-level meetings in which countries will be asked to improve their promises.

Another possibility is a more active private sector. On this, the main news is the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). According to Mark Carney, former governor of the Bank of England, its aim is to “build a financial system in which every decision made takes climate change into account”.

GFANZ consists of the world’s leading asset managers and banks, with total assets under management of $130tn. In principle, the allocation of such resources towards the net zero objectives would make a huge difference. But, Carney notes, $100tn is the “minimum amount of external finance needed for the sustainable energy drive over the next three decades”. This is daunting.

Needless to say, while it is possible to prevent businesses from doing profitable things, it is impossible to make them do things they consider insufficiently profitable, after adjusting for risk. If they are to invest at the necessary scale, there must be carbon pricing, elimination of subsidies to fossil fuels, bans on internal combustion engines and mandatory climate-related financial disclosures. But there must also be some way of getting vast amounts of private investment into the climate transition in emerging and developing countries, apart from China.

GFANZ calls for the creation of “country platforms”, which would convene and align “stakeholders — including national and international governments, businesses, NGOs, civil society organisations, donors and other development actors — . . . to agree on and co-ordinate priorities”. A big and controversial issue will be risk-sharing. The public sector should not take all the risks and the private sector all the rewards from the energy transition.

Much attention is devoted to the failure of developed countries to deliver the promised $100bn a year in finance to emerging and developing countries. This is symbolically important. But, as Amar Bhattacharya and Nicholas Stern of the London School of Economics note, it is small change: “Altogether, emerging markets and developing countries other than China will need to invest around an additional $0.8tn per year by 2025 and close to $2tn per year by 2030” on climate mitigation and adaptation and restoring natural capital. About half of this must come from abroad, mainly from private sources.

Yet the official sector, too, must do more. In this context, it is a real pity that greater advantage is not being taken of the recent issuance of special drawing rights. Of the total allocation of $650bn, some 60 per cent will go to high-income countries that do not need it and a mere 3 per cent to low-income countries. It is planned to on-lend $100bn of this from high-income to developing countries. This should be far more, in order to help deal with the legacy of Covid and the climate challenge.

In sum, if we compare the global discussion today with that of a decade ago, we have come a long way. But if we compare it with where we need to be, there is still a frighteningly long way to go. It is too soon to abandon hope. But to be complacent would be absurd. We need to act powerfully, credibly and quickly and, not least, we must agree to do so together. The task is great and the hour late. We can no longer sit and wait.

[ad_2]

Source link