[ad_1]

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Azovstal steelworks in Mariupol was a major exporter, its steel used in landmark buildings such as the Shard in London.

Today, the vast industrial complex is a symbol of Ukraine’s dogged resistance, bombarded by Russia as the last part of the city still in the hands of Ukrainian fighters.

While Azovstal remains under intense assault, its owner Metinvest, the country’s largest steel producer, has managed to resume production elsewhere. These are the first steps towards restarting the country’s iron and steel industry, which — including supply-chain accounts — makes up nearly 10 per cent of gross domestic product and employs half a million people.

ArcelorMittal, the world’s second-biggest steel producer, which owns a large plant at Kryvyi Rih in the south, has also been able to restart work after the industry all but ground to a halt when the invasion began at the end of February.

Volumes are much lower than they were, however, and while some exports have restarted, there are big logistical challenges, from the disruption to ports to the Russian missile attacks on the country’s railway network.

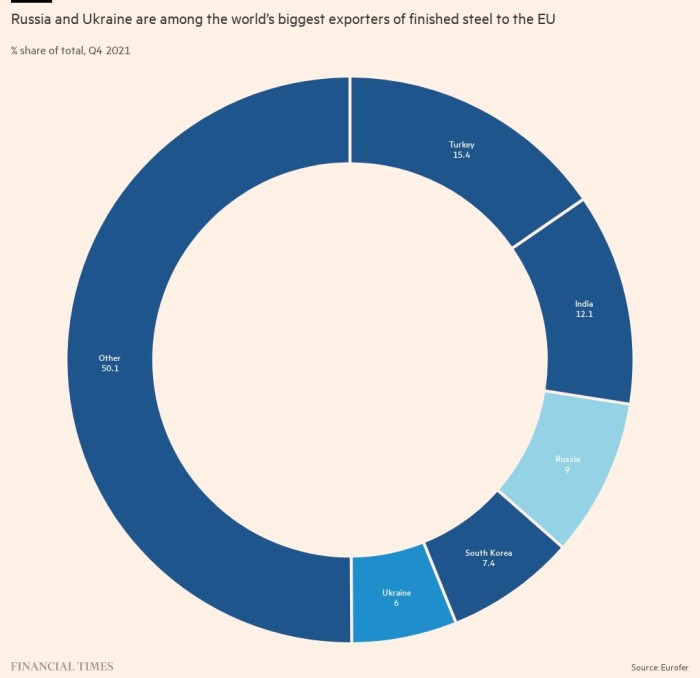

The loss of supplies has been felt all over Europe. Russia and Ukraine are among the world’s biggest steel exporters. Before the war, the two together accounted for about 20 per cent of EU imports of finished steel products, according to industry trade body Eurofer.

Many European steel producers relied on Ukraine for raw materials such as metallurgic coal and iron ore. Ferrexpo, the London-listed Ukrainian miner, is a major exporter of iron ore. Other manufacturing companies imported slab, semi-finished flat chunks of steel, as well as rebar, rods used to reinforce concrete in construction projects.

Russia’s invasion initially disrupted supplies and forced customers to source products from elsewhere.

Yuriy Ryzhenkov, Metinvest’s chief executive, said the company typically exported about 50 per cent of its products to the EU and the UK. “It is a significant problem, especially for countries like Italy and the UK. [Many] of their supplies of semi-finished products were coming from Ukraine.”

Italy’s Marcegaglia, one of Europe’s largest steel processing companies and a longstanding Metinvest customer, is among those that has had to scramble for alternative supplies. The company imported on average between 60-70 per cent of its slab from Ukraine.

“A situation of almost panic was created [in the industry],” said chief executive Antonio Marcegaglia. “Many raw materials became difficult to find.”

Despite the initial concerns over supplies, the company was able to keep production going at all of its plants, finding alternative sources in Asia, Japan and Australia.

Other companies found new suppliers too, including in Turkey. But the added cost has been considerable because prices soared after Russia’s invasion. “The problem is the knock-on effect, with prices being pushed up,” said one steel executive in the UK.

In parts of Europe, hot-rolled coil, a widely traded commodity used in manufacturing that is often seen as a benchmark for steel prices, jumped from €950 a tonne just before the invasion to more than €1,400 in April, according to price reporting agency Argus Media. It has since fallen back to trade at just over €1,200 at the start of May.

“The immediate response to the invasion was a precipitous run-up in prices. People were very concerned about supply,” said Colin Richardson, head of steel at Argus.

But he added that, after that: “The market started to slip quite quickly because people panicked and bought an awful lot of material. The supply disruption has not been quite as dramatic as people anticipated.”

If initial concerns over supplies have abated as companies including Metinvest and Ferrexpo have managed to keep some exports flowing and customers have found alternative supplies, worries about soaring input prices — for raw materials and energy — have intensified.

Eurofer warned this month that steel consumption in Europe could shrink by almost 2 per cent this year as a result of soaring energy prices, ongoing disruptions to supply chains and the shock of the war in Ukraine. A market contraction — which would be the third in four years — looks likely, it said.

Despite the disruption from the war, the impact on European industry has been cushioned by relatively high stock levels of steel coming out of the pandemic, said Karl Tachelet, deputy director-general at Eurofer. Some buyers have been able to sit out the current crisis.

Repercussions from the war, however, had “manifested [themselves] in other parameters — a very sharp but temporary increase in prices”, said Tachelet.

“Also, raw material prices and energy prices have exploded. These are shocks and they create immediate imbalances.”

Cost inflation was the biggest worry right now, he added.

It is a view shared by ArcelorMittal, which said this month that it expected steel consumption in Europe to decline by 2 to 4 per cent this year because of rising inflation, compared with its previous forecast of zero to 2 per cent growth.

Arcelor chief financial officer Genuino Christino said there had been some “tightness on the supply side which has created some difficulties for customers to source [materials]”. He added he thought this would be temporary but that it was “fair to expect there will be some reduction in demand”.

The European Commission and the US have both proposed suspending import duties on steel from Ukraine for one year but the big question is whether the country can keep producing — and exporting.

“It all depends on the state of the railways,” said the executive of one European steel company that sources iron ore from Ukraine.

“We do have alternatives for iron ore and coal. Poland is still a big producer of coal. We can get iron ore from Australia, Brazil. But our priority, as long as it works, is to get our raw materials from Ukraine,” he added, given its proximity.

Metinvest’s Ryzhenkov said the company was working with Ukraine’s government to open up new export routes to Europe.

“Yes, it’s difficult,” he admitted. While some routes are easier to plan, others require investment in new track and loading terminals. The company, he added, had managed to ship some materials to its facility in Bulgaria, and to customers in Romania and Hungary. It recently completed its first shipment since the war — of iron ore, bound for Algeria — through the Romanian Black Sea port of Constanța.

Despite the crisis, Ryzhenkov said he was confident the company would be able to recover. It has also refocused some of its operations in Ukraine to make steel plates for bulletproof vests for the military, as well as anti-tank traps to tackle Russian forces.

The company, he stressed, was still “operating and functioning” and able to service interest payments on its debts. Its assets in Europe and the US, which had previously been integrated into its operations, are also gradually adjusting as standalone businesses. Its steel rolling facilities in Europe have started procuring slabs from third parties to replace shipments from Ukraine.

Rating agency Fitch said this month that the company should be able to service payments on a $176mn bond due in April 2023 from “existing cash and incremental cash flow” provided there are no material adverse changes in production and shipment levels.

Ryzhenkov said: “It will take us some time to rejig the company . . . but it will be able to operate in the long run.”

[ad_2]

Source link