[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Welcome back. During Leslie Hook’s exclusive interview with US climate envoy John Kerry, the former secretary of state was asked to comment on BlackRock’s recent statement on climate-related shareholder resolutions. As we wrote on Wednesday, the world’s biggest asset manager said it would oppose most such proposals this year, saying that many were overly restrictive of management.

“I know Larry, and I think he’s been helpfully provocative in the last few years, and pushing the debate over shareholder versus stakeholder interests,” Kerry said, referring to BlackRock chief executive Larry Fink.

But “big companies are going to have to step up and toughen up and be part of the solution”, Kerry added, warning that without serious emissions cuts, “we’re in for a very significant disruption, which will only add to whatever disruption and chaos you see in the marketplace today”.

We give you a couple of new angles on that disruption and chaos in today’s edition. Simon has an interview with the former Labour party darling Chuka Umunna about his transition to the world of sustainable finance at JPMorgan, as it comes under fire for its lead role in financing the oil and gas sector. I write about the growing sums flowing towards the confrontational activists of Extinction Rebellion — who are increasingly making their presence felt in the US. Please read on. (Patrick Temple-West)

JPMorgan’s Umunna: Our fossil fuel funding reflects society

Chuka Umunna, the man once dubbed “a Barack Obama for Britain”, might seem to have taken an unconventional path to JPMorgan’s towering, glass-walled London office. Elected to parliament in 2010 aged 31, he rose to the highest echelon of the UK’s left-leaning Labour party. As shadow business secretary, he loudly opposed the sort of international corporate acquisitions that make investment bankers’ mouths water — including Kraft Heinz’s abortive bid for Unilever, in which JPMorgan played a lead role.

So Umunna’s decision last year to join the Wall Street giant, as its environmental, social and governance head for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, raised eyebrows. But the shift was less abrupt than it might seem, he insisted, when we met on the 31st floor of JPMorgan’s European headquarters in Canary Wharf, for a conversation that gave insights into the evolving ESG strategy of the biggest bank in the western hemisphere.

“The way I see it is that I’ve been working on ESG issues for the last 20 years,” Umunna said, citing his work as an employment lawyer before his years in liberal politics. “I don’t see it as kind of counter-intuitive at all.”

On one level, Umunna’s career move is yet another example of the revolving door that leads, increasingly conspicuously, from the House of Commons to lucrative financial sector jobs (here are some other recent examples). But this marquee hire’s assignment to ESG reflects the field’s dramatic rise to prominence on the financial sector agenda. And JPMorgan might have particularly good reasons to want a skilled politician on board as it grapples with the controversy over its environmental record.

In a scathing recent report, the Paris-based campaign group Reclaim Finance calculated total fossil fuel financing by the world’s 60 biggest banks over the past six years. JPMorgan topped the list by far, with $382bn — a full third higher than second-placed Citigroup.

“We reflect society,” Umunna told me. “Society has not come off oil and gas. We all want to get to the promised land where we do substantially reduce our reliance on oil and gas. But we do not, unfortunately, have renewables at scale right now to replace oil and gas . . . And that’s not JPMorgan’s fault. That is society’s challenge.”

Still, I noted, while many other banks have been scaling back their fossil fuel financing, JPMorgan’s rose nearly a fifth last year to $61.8bn, according to the Reclaim Finance study, including big transactions with Saudi Aramco and Russia’s Gazprom.

“For me, the starting point is 2021 onwards,” Umunna replied, pointing to new climate commitments made last year, including a pledge to reduce the “carbon intensity” — emissions relative to revenue — of its client roster in industries including oil and gas.

“People will bash us in terms of the carbon intensity of our financing portfolio,” Umunna added. “But don’t ignore what we are doing to support another vital part of this equation, which is the development of technology without which we won’t get to net zero.”

JPMorgan promised last year to provide $2.5tn in financing over 10 years to support climate action and sustainable development, and it has been ramping up its work with promising start-ups in the clean-tech space. Last month it handled a $650mn fundraising for Climeworks, a Zurich-based company building machines to suck carbon dioxide from the air.

But “new, funky, green” companies would not be able to drive the shift to clean energy on their own, Umunna added, arguing that big oil and gas companies will need to play an important role that will require large amounts of capital.

Umunna’s exit from politics came not through choice. Once seen as a contender to head the Labour party, he quit during the tumultuous leadership of Jeremy Corbyn and was then defeated at the 2019 general election. But he had never intended to remain in politics forever, he insisted, arguing that his private-sector role — aside from a pay package presumably somewhat chunkier than an MP’s £84,144 salary — comes with new opportunities for positive impact, amid politicians’ stuttering progress on climate action.

“I’m a democrat, so I say this without arguing against democracy,” Umunna said. “But four- to five-year election cycles are not conducive to long-term policymaking.”

In parliament, Umunna said, he witnessed “how the nation state had become quite emasculated given globalisation, and given that issues like the climate emergency know no borders. You need to tackle those things at a supranational level. And one of the ultimate private sector supranational institutions in the world is JPMorgan.”

As for the issue most keenly watched by the bank’s critics — JPMorgan’s exposure to fossil fuel development — Umunna declined to promise a reduction this year, pointing out that its carbon targets have a 10-year timeframe. If progress towards them proves slow, Umunna’s employer may need to call upon the public messaging savvy he learned in Westminster. (Simon Mundy)

Extinction Rebellion tactics loom for US chiefs?

On April 6, Nasa scientist Peter Kalmus walked up to a Chase bank branch in downtown Los Angeles and handcuffed himself to the door.

His action — and his subsequent arrest — was successful in drawing attention to Chase parent JPMorgan’s big role in financing fossil fuel businesses.

Kalmus is part of a group called Scientist Rebellion, which is a tip-of-the-spear activist group modelled on the global Extinction Rebellion movement. Scientist Rebellion’s approach is provocative: listed on its website are guides for window cracking as well as throwing pink slime or paint.

Now these climate activists are getting a new injection of cash. The Climate Emergency Fund (CEF), which has been a top funder of Extinction Rebellion and Stop the Money Pipeline for several years, recently announced that it had contributed $1.3mn to activists around the world, including in the US.

The board members of CEF, a US-registered charity, include Rory Kennedy, daughter of the late Senator Robert Kennedy, and Aileen Getty, heiress to the Getty Oil fortune. Adam McKay, director of the 2021 award-winning movie Don’t Look Up, has contributed $250,000 to its coffers.

In addition to Scientist Rebellion, CEF has funded protesters in West Virginia who have blockaded a coal plant with ties to Senator Joe Manchin.

Margaret Klein Salamon, executive director of CEF, told Moral Money that climate gatherings were “devastated” by Covid-19 and that action should return in the months ahead. Repressive policing tactics in the US had made climate protesting harder than in Europe, she added.

Donors are obviously skittish about giving to no-holds-barred activists, Klein Salamon said. But CEF has received about $224,000 in donations from workplace giving programmes. And Yelp, the business reviews platform, has reported donations to CEF through its corporate foundation.

Pressure on US companies has heated up. In April, Extinction Rebellion activists in New York City, a CEF grantee, halted newspaper production at the New York Times, News Corp and Gannet. These media companies had failed to cover the climate emergency and instead prioritised “the entertainment of subscribers”, activists claimed.

This month, Extinction Rebellion will join protests at the annual general meetings of JPMorgan and BlackRock to draw attention to climate concerns.

US chief executives should take note. (Patrick Temple-West)

Sustainable Views

If you’ve been enjoying Moral Money, you might want to check out Sustainable Views — a new service for sustainable finance professionals from the FT’s specialist arm, providing deep dives into ESG policy and regulation every Tuesday and Thursday. It’s a great resource to help you stay on top of developments in this fast-moving space.

Yesterday’s edition looked at the UK’s new Transition Plan Taskforce, and a round-up of a flurry of ESG policy activity in the past few days. You can sign up in a few seconds here.

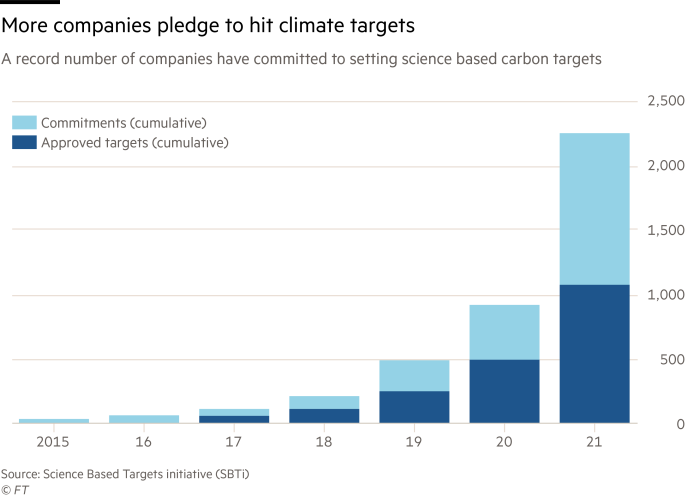

Chart of the day

At the end of 2021, 2,253 companies had made emissions reduction targets — or promised to do so — under the Science Based Targets initiative, which is fast becoming the key global benchmark for these corporate commitments. That’s more than double the number a year earlier. The companies have a combined market capitalisation of $38tn, more than a third of the total value of global stock markets, the SBTi said on Thursday.

Smart read

-

Private equity giant Carlyle is resisting pressure from climate campaigners to divest of its roughly $8.5bn in energy holdings, including from the production of hydrocarbons. Instead, Carlyle has decided that maintaining investment in oil and gas is necessary to meet global energy needs, writes our colleague Antoine Gara in an exclusive interview with Carlyle chief executive Kewsong Lee.

Moral Money Summit Europe

18th — 19th May 2022

In-Person & Digital | The Biltmore Mayfair, London I #FTMoralMoney

The time to make ESG a reality is now, but is the market ready to join together to make it happen?

Find out at the FT’s Moral Money Summit Europe, taking place in-person in London and live online. Come along and connect with leading policymakers, investors, senior business executives and industry thought-leaders who will share their plans for the next stage of their ESG journey. As a premium subscriber, you can join the event with a complimentary virtual pass when you register with the promo code: Premium2022. Register now

[ad_2]

Source link