[ad_1]

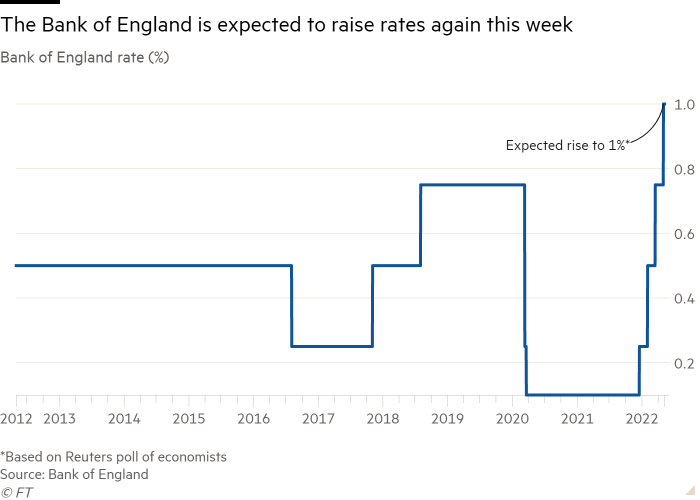

The Bank of England is expected to raise interest rates to their highest level since 2009 on Thursday, as the central bank seeks to strike a balance between tackling record inflation and not taking action that would exacerbate the UK economic slowdown.

Increasing rates from 0.75 per cent to 1 per cent would mean the BoE hits a self imposed threshold to reveal next steps in its plan to reduce billions of pounds worth of assets built up over 12 years of quantitative easing following the financial crisis.

Financial markets were expecting the BoE Monetary Policy Committee to raise rates by half a percentage point this week, but have shown signs of revising their calculations down in recent days, with most economists now predicting a 0.25 percentage point increase.

The consensus among economists is that the MPC will decide to move more cautiously as UK households are squeezed by inflation, leading to lower demand and slower economic growth.

The pressure on the BoE to tighten monetary policy stems from persistent and broad increases in prices alongside a tight labour market, and disruption to global supply chains caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the coronavirus pandemic.

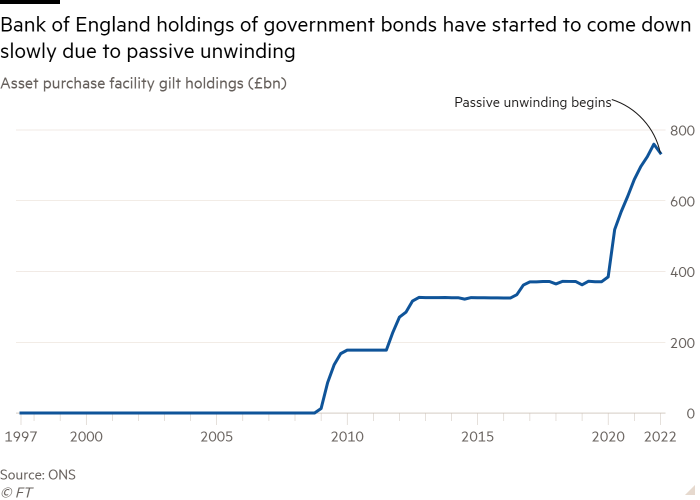

More uncertainty surrounds the BoE’s intention for unwinding quantitative easing, but some economists expect the central bank to at least announce a plan to begin asset sales at some point this year.

Analysts at Bank of America said any rate rise would not prevent headline inflation rising to about 9 per cent this year, while some economists, including those at Capital Economics, expect price growth to increase at a double digit rate in the autumn. Consumer price inflation hit a fresh 30-year high of 7 per cent in March.

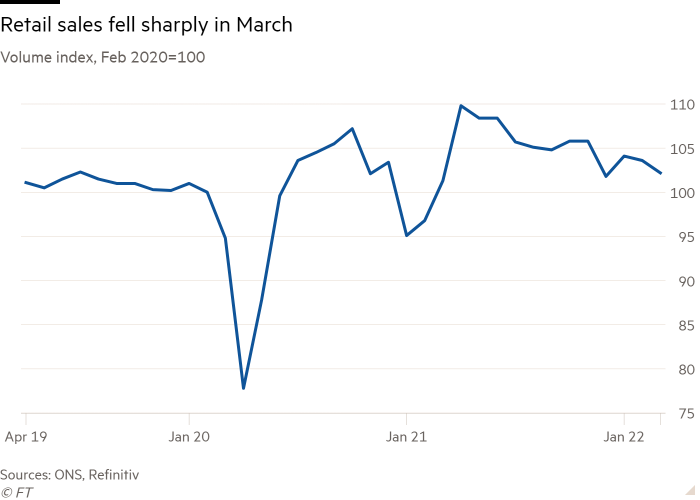

But the need for aggressive action to curb inflation is offset by signs of weakening demand, as households struggle with soaring energy bills alongside broad-based increases in the prices of goods and services.

Chris Hayes, economist at HSBC, said: “There is a growing argument that the energy shock driven inflation of today — to the extent that it squeezes on real incomes — means lower inflation tomorrow.”

The prospect of the squeeze on incomes taking the wind out of the economy is something that Andrew Bailey, governor of the BoE, is concerned about.

Speaking on the sidelines of the IMF and World Bank spring meetings last month, he said the MPC was “walking a very tight line” between tackling inflation and not pushing “too far down” on prices.

Economic data last week further buttressed the argument that inflation is beginning to damp economic activity. UK retail sales data for March showed volumes fell by a more than expected 1.4 per cent — one of the first signs that high prices are having a negative impact on consumer spending.

Growth in gross domestic product slowed to just 0.1 per cent in February, from 0.8 per cent in January.

Not all economists are convinced, however, that a weakening economy will bring prices down, with some predicting a very real risk of prolonged stagflation — a term used to describe a period of low GDP growth and persistently high inflation.

Ruth Gregory, economist at Capital Economics, said “various indicators are telling us . . . that second round effects of the initial inflationary shock could keep inflation beyond the bank’s [2 per cent] target rate despite a weaker economy”.

She added that a lack of migrant workers due to Brexit, along with a significant drop in labour force participation after the pandemic, would keep the jobs market tight and raise wage inflation.

“Rates will need to rise further” despite the risk of recession, in order to “lean against the risk that inflation becomes sticky as wages rise”, said Gregory.

As the MPC attempts to strike a balance between curbing inflation without weighing too heavily on GDP growth, it will have to decide whether to start active sales of the government bonds it owns.

In August 2021, the MPC decided that reaching an interest rate of 1 per cent would be the threshold at which it would “actively consider” selling the gilts on its books. In February this year, it stopped reinvesting the proceeds of maturing bonds when rates increased to 0.5 per cent, a clear signal that its balance sheet would begin to reduce in size.

Given the maturity of its current holdings of government bonds, a “passive” unwinding would be slow and reaching the 1 per cent rate threshold would give the MPC an opportunity to increase the pace at which it shrinks the central bank’s balance sheet.

However, economists expect the MPC will be wary of not disrupting markets. Bailey said last month the BoE would not be “selling bonds into a fragile market” and would be flexible to changing “financial conditions”.

The BoE may feel that it has time on its hands, as unlike the US Federal Reserve, it has not shown any inclination to use a reduction in its balance sheet to try to raise long-term government borrowing costs, said James Smith, economist at ING.

The focus of the BoE is more likely to be on reaching an “equilibrium level” of government bonds which leaves enough reserves at commercial banks to meet their demand for money, according to Sanjay Raja, an economist at Deutsche Bank.

The BoE has not indicated what this level would be, but Bailey has repeatedly said it would be markedly higher than the position before the financial crisis.

[ad_2]

Source link