[ad_1]

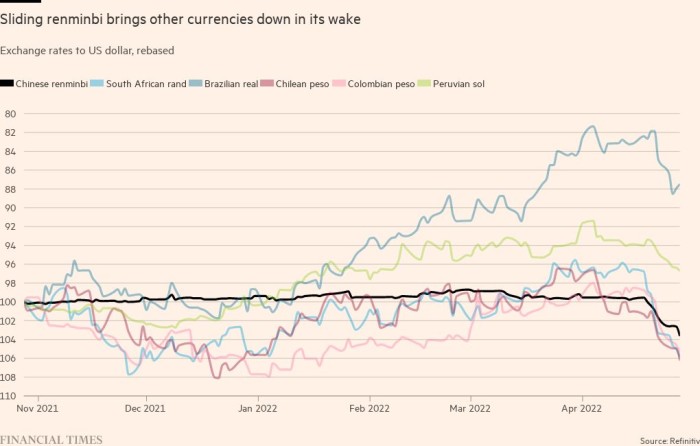

China’s currency has fallen steeply against the dollar over the past two weeks, hit by the economic impact of the country’s Covid lockdowns, the war in Ukraine and the prospect of tighter US monetary policy. But the renminbi has not moved in isolation: analysts warn it is dragging down other emerging market currencies with it, including those outside of the Asian manufacturing complex.

With food and energy prices soaring, currencies of commodity-exporting emerging markets such as Brazil and South Africa are among the few to have gained any advantage from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February. Many such currencies also benefited from Chinese demand for industrial commodities, such as copper and iron ore, earlier this year.

In April, however, the combination of China’s slowing economy and the global fallout of the war sent emerging-market currencies around the world into reverse.

Yerlan Syzdykov, global head of emerging markets at Amundi, says the proliferation of strict lockdowns in China is causing weakness across the economy. The worst-case scenario projected by Amundi’s analysts is that lockdowns will cause a 10 per cent reduction in manufacturing and an 18 per cent fall in steel production.

Amundi was bearish on Chinese growth before the recent lockdowns began. Its house view was for GDP growth this year to come in at almost a full percentage point below the IMF’s forecast of 4.4 per cent. But even that figure is now under pressure, said Syzdykov.

“This is having a negative effect on commodity prices — those countries especially in Latin America that have had a positive effect so far on their terms of trade, they are going into retreat,” he said. “This will definitely affect their longer-term prospects.”

In late April, the Brazilian real was one of the best-performing currencies in the world earlier this year, with a 20 per cent gain against the dollar. A sharp pullback since then has left it a more modest 13 per cent higher.

Meanwhile, the Peruvian sol and Colombian pesos have fallen heavily. The Chilean peso and South African rand, have wiped out almost all of this year’s gains.

Central banks in Brazil and several other emerging markets reacted early to the prospect of rising US interest rates and a stronger dollar by lifting borrowing costs from the first half of last year.

But while the expectation before the Ukraine war was that inflation in developing economies would peak around the middle of this year, Syzdykov said, this was now likely to be delayed by at least another three months — potentially putting more sustained pressure on those countries’ currencies.

It is only after that point that a fresh recovery might ensue, Syzdykov suggested. “That would be the moment when international investors start going back in, and those flows will help to propel those currencies again,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link