[ad_1]

Even before the £700 rise in annual energy costs for UK households landed this week, 36-year-old Leigh Sopaj was struggling to pay her bills.

At the start of each week Sopaj loads £30 on to a prepaid electricity meter, but her credit is dwindling faster and faster. “I used to have £20 left around the middle of the week,” she said, “but now it’s already down to £11. The bills are just getting harder and harder to pay.”

Sopaj, who lives in a suburb of Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, ranked among the 20 per cent most deprived areas of the UK, is among the 6.3mn households facing “fuel stress” according to the Resolution Foundation, a think-tank — after the number of homes affected tripled overnight.

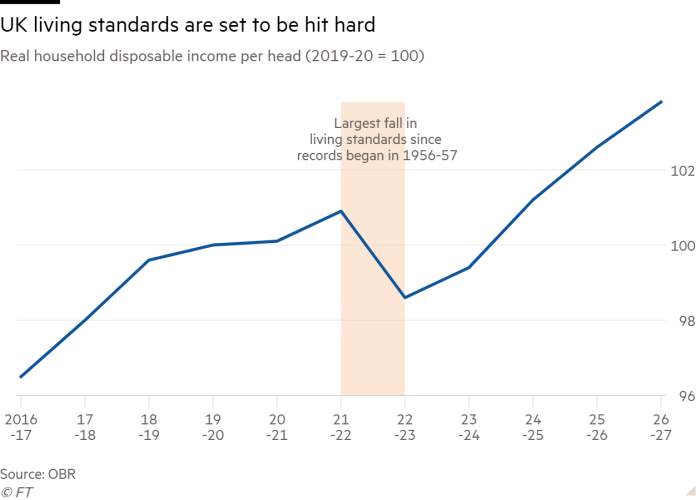

And with the UK’s energy price cap predicted to jump by another £600-£800 in October, alongside increases in council tax, inflation heading towards 8 per cent and petrol prices rising by 50p a litre since January, families are confronting the sharpest drop in living standards since records began in 1956.

As a result, local authorities and voluntary organisations are looking for innovative ways to address a cost of living crisis that will ensnare families who would not ordinarily use emergency services such as food banks.

One such scheme is the Lillington Community Pantry in Warwickshire in England’s West Midlands. “Subscribers” pay £5 to select food items from shelves stocked with surplus supermarket goods. The aim is to help householders like Sopaj stretch budgets that are being rapidly eroded.

The pantry, which is run by a charity, Feed the Hungry, on behalf of Warwickshire county council, consciously differs from a traditional food bank where recipients are simply handed pre-packed bags of food.

It aims to provide a “shopping experience” and a host of other preventive services from debt counselling to health advice and cookery classes, that the council hopes will help stabilise families teetering on the edge of a poverty precipice.

“For a lot of people it’s a slow decline, a spiral downwards, so what we’re trying to do is catch them before they hit the bottom,” says Heather Timms, a Conservative member of the council, which has invested nearly £350,000 in the pantry.

The scheme, which blends government seed money with charity knowhow and the work of volunteers, is being held up as a model of how local governments can look to harness “community power” to bolster already-stretched services.

Pantry users can seek expert advice from on-site groups such as Citizens Advice, whose representative Paul Carter is available for on-the-spot consultations.

“Something as simple as tips on budget planning for foreseeable financial events like birthdays and Christmas — and not promising your child what you can’t afford — can help people live within their means,” he says.

The idea of expanding community involvement in delivering public services is supported by central government and was included by the levelling up secretary Michael Gove in a white paper in February, which set out the government’s prospectus for reducing inequality across the UK.

The paper included a promise to try out “community covenants” in which councils, public bodies and local groups make formal agreements to “empower communities to shape the regeneration of their areas and improve public services”.

Critics of the government, including Angela Rayner, deputy leader of the opposition Labour party, have said such schemes are no substitute for proper funding of local government services, which have been hit with 30 per cent budget cuts during the past decade.

At a recent conference on community empowerment, Rayner, while welcoming the concept, accused the government of failing to really strengthen communities, instead favouring a “bit of money in a pot here, a little project there”.

But promoters of grassroots engagement argue the sheer scale of the cost of living crisis, combined with the revival of volunteering during the Covid-19 pandemic, has created a moment to reassess the role of community in delivering services.

Adam Lent, chief executive of the think-tank and local government network New Local, said the policy debate had moved on from the ideas of the “Big Society” proposed by David Cameron, former prime minister and Conservative leader.

“Cameron’s ‘Big Society’ idea was that the state would take a step back and the voluntary sector would step up. This is a different concept: it says that the state is an important catalyst for change and community power,” he said.

As an example, New Local cites the Wigan Deal where Wigan council in Greater Manchester has mobilised volunteers and schools to improve local parks and recycling, staff libraries and create friendship groups.

Danny Kruger, a Conservative MP who was asked by the prime minister Boris Johnson to report on how to capitalise on the volunteering spirit ignited during the pandemic, believes necessity will prove the mother of invention.

“We now have much more of a ‘burning platform’ than in that era of ‘Big Society’,” he said. “There is a growing understanding that we need a stronger society because the resources of the state are simply insufficient to meet the need.”

Back in Lillington, the aim is that seed money that has been invested in the pantry will replicate the success of a similar scheme in neighbouring Coventry, which has more than 130 participating families.

Charles Barlow, head of six “community power” projects for Warwickshire county council, including an orchard and a scheme to help the elderly remain in their own homes longer, believes demand will increase as cost pressures on families mount.

“If it works and we get the volume of community buy-in we’re looking for, then the hope is that the project becomes self-sustaining,” Barlow said.

Faye Abbott, who runs the Lillington pantry, said the hope was to create a hub around which people can coalesce in hard times, with cooking classes and activities for children with few treats in their lives.

In its second week of opening, she recalled how one small boy came running in and immediately picked up a packet of Angel Delight pudding mix.

“It was a small thing, but clearly so important to him,” she said. “This is not just about helping people on means-tested benefits. There are people working who still cannot afford to pay the bills, and that group is getting larger and larger.”

For Sopaj, who cannot afford swimming lessons for her two-year-old son, Hudson, the pantry will enable her to pick up about £30 worth of food for a £5 fee. This will help her get through weekends when her teenage children come to stay. “They just eat so much,” she says. “The pantry will help to get me through.”

[ad_2]

Source link