[ad_1]

This article is the latest part of the FT’s Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign

When my father taught adult numeracy in Birmingham in the 1980s he would ask each new class what they hoped to learn. On one occasion, a woman who worked as a lunchtime supervisor said she wanted to know about percentages. Her colleagues were telling her that the pay rise they had been offered was not enough, but she had no way of judging because she didn’t understand the concept of a percentage increase.

Understanding percentage change is one of those mathematical fundamentals that often surfaces in financial literacy discussions. The Money Advice Service’s original 2015 report used it as a key measure, asking people in their survey to say how much £100 paid into a savings account would be worth after a year if it accrued interest at 2 per cent. More than a third couldn’t answer correctly.

So arguments, such as that made in FT Money by Robert Halfon, chair of the House of Commons Education Select Committee, for more targeted teaching of financial literacy in schools, are rather putting the cart before the horse.

Without the core mathematical skills, lessons about fixed versus variable interest mortgages, or how student loan repayment rates are pegged to inflation, are hardly going to hit the spot. Financial literacy is in any case most effective if taught at key life stages, in the context in which it is going to be useful, rather than as a generic skill.

Perhaps, then, the biggest service we could do for future financial literacy is to embed mathematical skills for today’s pupils. The UK lags behind the OECD average in these skills, with more than half of working-age adults estimated to have low basic numeracy, meaning that they cannot properly read a payslip or convert a weekly bill into a monthly or annual amount. Low functional numeracy affects all age groups and is highest in deprived areas.

The food writer and poverty campaigner Jack Monroe blew open the debate on poverty and inflation with her calculations of recent rises in supermarket food prices, even succeeding in putting the Office for National Statistics on the defensive.

How many others, lacking Monroe’s formidable skills, do not have the mathematical agility to compute increases in the cost of their weekly food shop? Or calculate the combined effect of the expected 50 per cent increase in fuel bills in April and of a 1.25 percentage point (not the same, you will note, as 1.25 per cent) increase in national insurance contributions?

Working out these changes must surely be a high priority for financial literacy as people brace for these shocks.

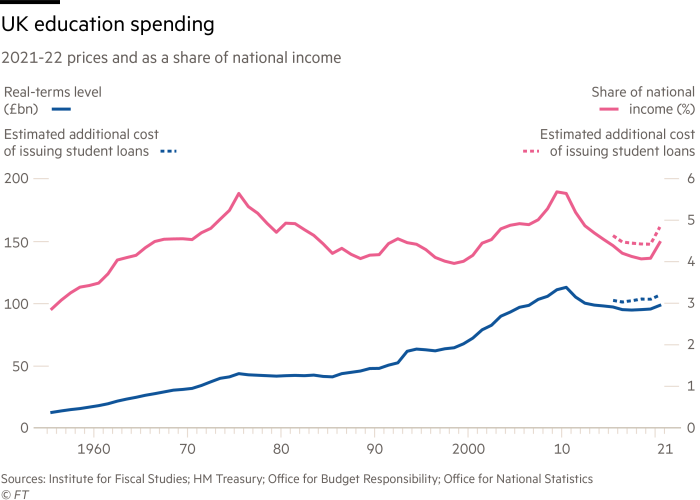

So what resources are we putting into this mathematical levelling up? Not enough, it seems. In our recent book, After the Virus: Lessons from the Past for a Better Future, my co-author, Professor Simon Szreter of Cambridge university and I, took a long view of investment in education, going back to the post-1945 social contract. Spending on education was massively expanded, nearly doubling as a percentage of GDP from 2.9 per cent in 1955-56 to peak at 5.6 per cent in 1975-76.

By 1972 all children were receiving free, mandatory education up to the age of 16. As we show, these were years when productivity grew on average by 2.4 per cent annually, the UK’s highest ever, and in startling contrast to the anaemic 0.3 per cent seen since 2007.

The crises of the mid-1970s ushered in neoliberal Conservatism and the retreat of the state. Tax cuts went hand in hand with a drastic reduction in the percentage of national income spent on education. Only private schools continued to increase the amount that was spent per pupil.

New Labour later reversed the cuts, investing at all stages from early years, through schools and higher education. But Tory austerity again reduced the share of GDP spent on education, paring it once more down to 4 per cent, the same level as 60 years earlier. In real terms, spending actually fell. That this happened at a time when most young people were staying in education until the age of 18 with nearly half progressing to university is quite some feat.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies published its 2021 report on education spending, with the stark observation that “the cuts to education spending over the last decade are effectively without precedent in post-war UK history, including a 9 per cent real-terms fall in school spending per pupil and a 14 per cent fall in spending per pupil in colleges. Whilst we have been choosing to spend an ever-expanding share of national income on health, we have remarkably reduced the fraction… we devote… to education.”

We are investing, it seems, to meet the rising needs of the older population for health and care, while neglecting to invest in the young.

That is not sustainable. It is also deeply inequitable. Before the pandemic, education spending had been falling more rapidly in deprived than in prosperous areas. Then, when Covid kept children out of the classroom for months on end, it was, as our book shows, those with fewer resources who fell behind.

Underfunded catch-up programmes are struggling to deal with the aftermath and an alarming 80,000-100,000 children have gone missing from school rolls altogether.

But, unexpectedly, a door has opened. A boost to the national coffers has materialised from the UK’s plummeting fertility rate, offering the Treasury the prospect of savings as classrooms and schools are closed in the coming years.

We could decide not to bank the windfall. We could use that money to invest in a better education — and maybe higher skills and earnings — for the smaller number of children who will be around to pay taxes to support our old age.

Providing all pupils with secure mathematical skills whatever their background will equip them with an essential grounding for managing their household finances effectively in the future. For the economy as a whole, the payback should come in higher productivity as it supports the transition to the high-skill, high-wage economy that we aspire to.

After the Virus: Lessons from the Past for a Better Future, Hilary Cooper and Simon Szreter, is published by Cambridge University Press. £12.99.

[ad_2]

Source link