[ad_1]

Ground handlers and refuelling staff at Heathrow airport are gearing up for strike action over the February school holiday. Three thousand Airbus workers could walk out in March. Bin lorry and bus drivers across the UK are demanding — and in some cases winning — big pay rises after watching wages shoot up for truckers with similar skills.

After a pandemic-induced lull in industrial action, the current pay bargaining season is shaping up to be one of the most confrontational in years.

It is being closely watched by policymakers at the Bank of England, who are acutely worried that a surge in inflation — initially caused by higher global prices for goods and energy — could become a lasting phenomenon if it gets baked into domestic wage settlements.

Most forecasters expect the monetary policy committee to raise interest rates when it meets on Thursday, to avert the risk of a so-called wage-price spiral developing, when workers demand pay rises to match higher living costs and companies raise prices to protect their margins in a repeating, self-fulfilling process.

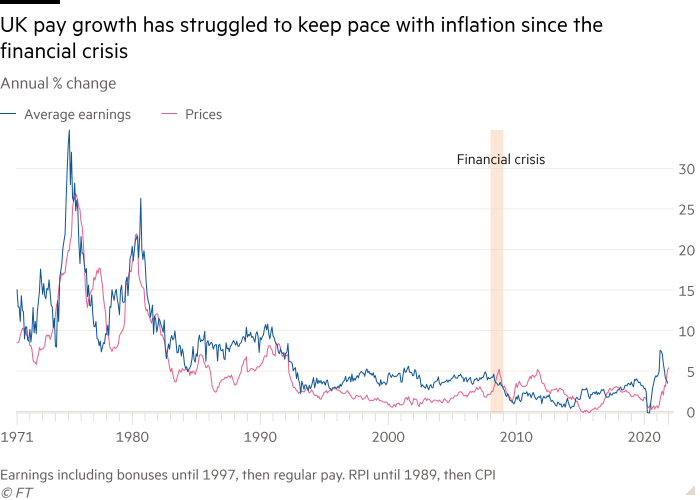

This would be a radical reversal of the prevailing trend. Since the 2008 financial crisis, wages have barely risen in real terms, with workers being forced to swallow lower living standards in years when higher oil prices or the exchange rate effects of Brexit pushed up inflation.

But as Catherine Mann, an external MPC member, warned last month, the current environment of higher price inflation and tighter labour markets could “herald a regime change”.

“If the psychology of higher inflation is to take root, it will do so through wages and pay settlements,” said Neil Shearing, chief economist at consultancy Capital Economics, adding that even if unions’ power had waned over time, workers could still force up wages when they were in short supply and willing to quit for a better offer.

That is the situation now in the UK, where for the first time on record there are almost as many vacancies as there are jobseekers.

Kevin Rowan, head of organising at the Trades Union Congress, said the upturn in industrial action reflected the “zeitgeist” among workers who knew they were needed and were ready to “flex a bit of muscle”.

Despite this, wage pressures have so far been concentrated in sectors with acute shortages. Advertised wage rates tracked by the job search site Indeed have climbed by more than 6 per cent over the past year for roles in hospitality, construction, manufacturing and logistics.

But they have been flat or falling in other areas, including sales, management and the legal sector. Across all jobs advertised on Indeed, wage rates have risen by about 4 per cent — stronger, but not unduly so compared with pre-pandemic growth rates.

The Office for National Statistics’ headline measure of pay growth showed average weekly earnings, excluding bonuses, were 3.8 per cent higher than a year earlier in the three months to November, similar to the nominal growth rate seen in the summer of 2019.

This means that for most people, even if wages are rising, prices are rising faster. And while companies are worried about losing staff to competitors, they are also facing many other pressures.

“Businesses have half a gazillion reasons to push back against wage increases as much as they can because all their other costs are increasing,” said Fabrice Montagné, chief UK economist at Barclays.

Yet even if pay is lagging behind prices, it is still rising fast enough to keep inflation above target for longer than the BoE would find comfortable. And the pressures are building — not only in sectors such as hospitality or care that have become less attractive to work in since Covid.

The BoE’s agents’ survey found in December that companies that had previously frozen pay were having to raise it mid-year to stop staff leaving, while some employers offered increases as high as 40 per cent to tempt staff from elsewhere.

Data gathered by the research group XpertHR suggest pay settlements have become more generous even since the start of the year.

Sheila Attwood, managing editor of XpertHR’s pay and HR practice, said early responses showed that pay awards agreed in January would be the highest since December 2008 (when they averaged 3.6 per cent), with pay freezes and low awards now a rarity.

Most economists still do not expect wage growth to take off on any scale comparable with the 1970s, when the term “wage-price spiral” was coined.

But Steffan Ball, chief UK economist at Goldman Sachs, said that with the labour market tighter than it had been for decades, wage growth would be “sharply above” the BoE’s November forecast and strong enough to justify continued monetary tightening during 2022.

MPC members have signalled that they did not think it would be possible to keep inflation under control unless wage growth remains in check, even though this will mean falling living standards.

Mann said last month that monetary policy needed to “temper the 2022 expectations for wage and price increases”, despite the painful implications for households.

“I know that there has been a lot of talk already about the cost-of-living squeeze,” she said. “It is not my goal to make this worse than it already is — to the contrary, I aim to bring inflation back down to target such that workers can enjoy real wage gains from their labour.”

[ad_2]

Source link