[ad_1]

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Imagine every death certificate issued in a particular country is lined up in front of you in 10 piles, from those who lived to the ripest of old ages on the left, to the most tragic young deaths on the right.

In the pile furthest to the left are the most fortunate people in society: those who won the lottery when it came to genes, jobs and outcome. Today, in developed countries, the average certificate plucked from this pile will show an age at death in the late nineties. This is as true of deaths in the US as it is of those in Italy, Japan or Sweden. If you’re among the most fortunate in America, you will live about as long as the most fortunate anywhere in the world.

In the rightmost pile, you’re looking at the least fortunate. Whether it was genetic make-up, socio-economic setbacks, or simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time, these people’s lives ended tragically early. But sifting through the certificates, it will become clear that the fates of the disadvantaged are much more country-dependent. Even the most disadvantaged in Japan and Switzerland typically make it to 60. In France, Germany and Britain, they die at about 55. In the US, it’s just 41.

Much has been made of America’s life expectancy deficit, but focusing on a statistic which is an average for the whole population masks truly staggering disparities at the extremes. For men at the bottom of the US economic ladder, it’s even worse. My calculations suggest the average age of death in that group is just 36 years old, compared with 55 in the Netherlands and 57 in Sweden.

It hasn’t always been this way. In the 1980s, the most disadvantaged Americans lived about as long as their counterparts in France. By the early 2000s, lives at the bottom had lengthened considerably, and while a deficit was opening up, it wasn’t worrisome. But in the past decade, the lives of America’s least fortunate have shortened by an astonishing eight years. That gap with France has become a yawning gulf. What has happened?

It is common to reach for economic explanations. Widening inequalities in American longevity must be due to widening inequalities in American incomes. Shorter lives for those at the bottom must be due to a decline in material wellbeing. But the evidence suggests otherwise.

US income inequality was rising throughout the 1980s and ’90s while the lives of the poorest Americans were lengthening, and inequality has been flat as disadvantaged deaths have increased. Rates of material poverty in America have fallen especially steeply over the past decade, just as the life expectancies of the least fortunate have nosedived. Plus, its poorest citizens have incomes on a par with the poorest across the developed world.

To understand what is going on, we need to look not only at length of life, but at the causes of those early deaths.

In most wealthy countries, if you’re desperately unlucky in the longevity stakes, you succumb to cancer before you reach 60. But if you’re unlucky in the US, you die from a drug overdose or gunshot wound by 40. Which brings us again to the most shocking statistic: among the least fortunate 10 per cent of American men, the average age at death is 36.

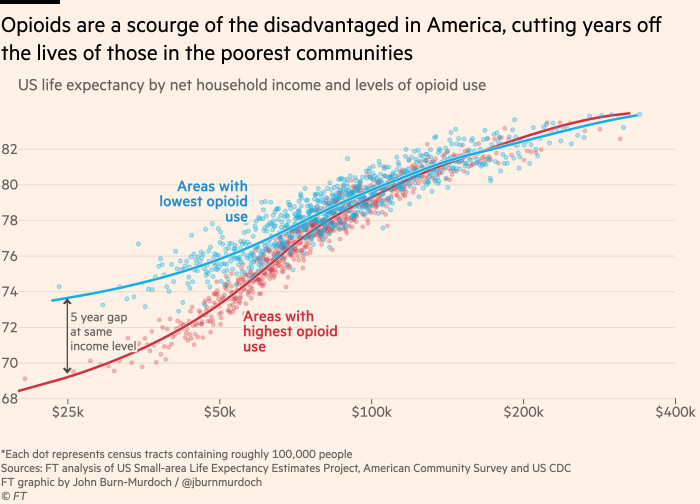

Looking at different regions within the US paints a similar picture. Conditions such as obesity shorten the lives of rich and poor alike, but the most uniquely American afflictions have steep socio-economic gradients. Wealthy Americans who live in the parts of the country with high opioid use and gun violence live just as long as those who live where fentanyl addiction and gunshot incidents are relatively rare. But poor Americans live far shorter lives if they grow up surrounded by guns and drugs than if they don’t.

The reason, then, that the least fortunate in the US live such short lives compared with their counterparts elsewhere in the developed world is not economic. In the case of guns it is sociopolitical, with entrenched positions preventing progress. And in the case of opioids, it was triggered by predatory pharmaceutical practices absent elsewhere in the world.

The number of disadvantaged people in the US has not ballooned, and nor have they become poorer. But for the least fortunate Americans, their circumstances are a death sentence in a way that is not true anywhere else.

[ad_2]

Source link