[ad_1]

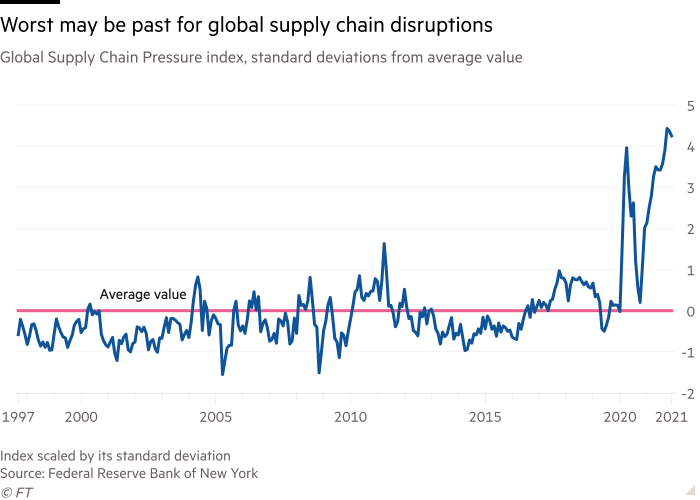

Supply chain pressures remain well above their pre-pandemic levels, but there are signs that global trade relations could start to normalise this year — even as many countries face rising cases of the Omicron coronavirus variant and persistently high inflation.

A gauge of worldwide supply chain constraints produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York shows that such pressures reached their highest point in October 2021. But the index — which is based on 27 variables, including global shipping rates and air freight costs — ticked slightly lower in both November and December.

Some analysts believe that the squeeze in certain areas will continue to ease off in the coming months.

“Over the next year, it seems likely that some supply chains will resolve themselves while others may prove more persistent,” said Simon Edelsten, manager of the Artemis Global Select Fund and Mid Wynd Investment Trust.

The swift reopening of the global economy had “caught some by surprise last year,” said Edelsten. But some sectors, such as the automobile industry — which had suffered from semiconductor shortages — “seem to be improving,” he added, pointing to Toyota’s and Tesla’s recent sales figures.

Companies around the world have been hit by pandemic-related pressures such as factory shutdowns and bottlenecks, as the introduction of border restrictions by many governments coincided with booming consumer demand. Disrupted logistics networks have caused shipping costs to mount and have delayed deliveries.

“Last year was a perfect storm for supply chains. Not only did we have Covid disrupting production, but fiscal stimulus boosted demand and the Suez Canal closure caused months of disruption,” said Guy Foster, chief strategist at wealth manager Brewin Dolphin.

Supply chains could prove more resilient this year, as inflation hits consumers’ spending power and more companies adapt to Covid-safe production protocols. Moreover, a surplus in orders from the end-of-year holidays could allow inventories to replenish while older deliveries come through, said Foster.

Supply-chain strains have contributed to persistently high inflation. Fresh figures on Wednesday showed that US consumer prices rose by an annual 7 per cent in December, their fastest pace in almost 40 years. Separate data on Thursday showed that US wholesale prices rose at an annual clip of 9.7 per cent last month, though this was slightly below economists’ forecasts.

Even as macroeconomists are generally optimistic about the year ahead, most indicators of supply-chain stress remain much higher than where they were pre-coronavirus. Container shipping rates peaked in October, but are still more than five times their level in January 2020, according to data provider Harpex.

Richard Flax, chief investment officer at digital wealth manager Moneyfarm, expects the supply-chain recovery to happen “slowly” over the course of 12 to 18 months. Improvements linked to investments in better supply security and plant efficiency would take time, he added.

Timothy Fiore, chair of the Institute for Supply Management, noted “indications of improvements” in labour resources and supplier delivery performance. But customer inventory levels remain very low, while backlogs of orders are “staying at a very high level,” he added.

“The fly in the ointment is China,” said Foster, who sees “one major risk” for supply chains this year. A new wave of coronavirus infections, paired with China’s “zero-Covid” policy could lead to port closures, which would further disrupt shipping, he said.

[ad_2]

Source link