[ad_1]

Receive free US-China relations updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest US-China relations news every morning.

After President Joe Biden announced a ban on US investment in some of China’s critical tech industries, the founder of a Shanghai-based semiconductor start-up felt forced to react.

“After the news came out, I was determined to move the team out of China, at least part of the team,” the person said, asking not to be named because of the sensitivity of the subject. “Otherwise, the financing will be very limited.”

The US ban, announced in an executive order on Wednesday and due to come into force next year, aims to block investment in quantum computing, advanced chips and artificial intelligence in an effort to stop China’s military from accessing American funding and knowhow.

For their part, US investors are trying to work out the potential impact of Biden’s order on their holdings in China and weighing up strategies to comply or exit.

Private equity groups General Atlantic, Warburg Pincus and Carlyle Group have poured billions into China in recent years as they sought the huge returns from betting on the nation’s emergence as a technological superpower.

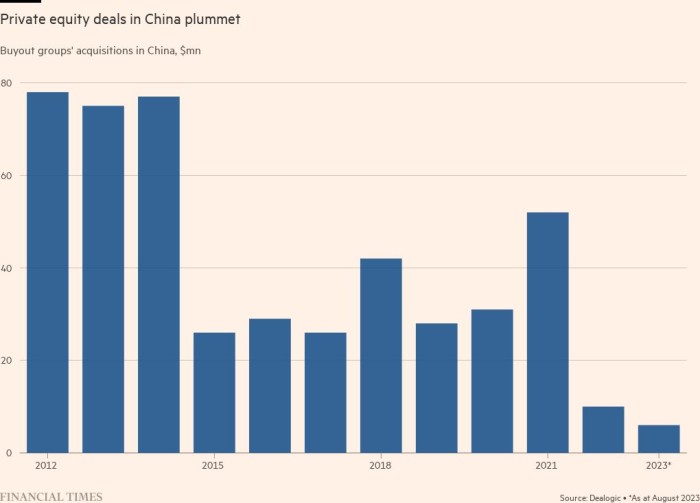

Seeing the writing on the wall, though, many have already pulled back. Buyout groups struck deals in China worth $47bn in 2021, but that fell rapidly to just $2.4bn in 2022 and $2.8bn so far this year, figures from Dealogic show.

One of the most drastic pre-emptive moves came from Sequoia Capital. In June, the Silicon Valley venture capital firm said it was carving its China arm from its US and European operations, and also spinning off its India business.

“The era of American venture capital firms investing in China is over now,” said one European venture capital investor.

However, dozens of other US venture funds have continued to invest or retain stakes in Chinese companies. Among them are GGV Capital, GSR Ventures, Walden International and Qualcomm Ventures, which a congressional committee on Chinese investment announced it would be investigating last month.

General Atlantic, which has invested in ByteDance and fast-fashion retailer Shein, said in June that the country still presented “great opportunity”.

The US order targets only three specific sectors, a strategy described by national security adviser Jake Sullivan as “small yard, high fence”. Those are already largely covered by foreign investment screening rules that China introduced in 2021.

But the order’s inclusion of AI — a technology that businesses across many sectors are using — could deter US investors from buying into a wide range of Chinese companies.

“Artificial intelligence is everywhere and most of it is dual use . . . you can’t sort of put it in a box,” said Marcia Ellis, global co-chair of the law firm Morrison Foerster’s private equity practice.

US investors might question, for example, whether they could buy a warehouse company that used AI if the same technology were used by the military, she said.

Uncertainty extends to the role of so-called “limited partners”, such as US public pension funds, which provide the capital for private equity and VC funds to invest.

The administration does not plan on imposing restrictions on limited partnerships in cases where the contribution that the LP makes is purely financial and the firm does not have any ability to influence the Chinese fund’s decision making and operations.

That could allow Chinese venture capital groups that have raised money from US investors, such as HongShan, the firm led by Neil Shen that was spun off from Sequoia, to continue raising and investing money from American LPs.

But the investment would have to be below a certain threshold, which will be determined as the administration fleshes out the details of the final rule.

US officials said they were focusing on American private equity and venture capital firms, in addition to joint ventures, because these firms could provide Chinese groups with valuable “intangible” benefits such as introductions to experts and other firms in their investment networks.

Some Republicans have called on the Biden administration to broaden the scope of the restrictions, saying they will not have the desired outcome of slowing China’s military modernisation.

The Financial Times reported last week that Mike Gallagher, the Republican chair of the House China committee, had urged Biden to include public market investments in the executive order.

Jonathan Gafni, head of the US foreign investment practice at the law firm Linklaters, said lobbyists would have plenty of opportunity to consider the final rules over the coming months.

“[The administration] are not putting too firm a stake in the ground yet because they realise that there is going to be a lot of pushback if the application is too broad.”

But the new ban is likely to make US investors more cautious about committing money to new private equity funds.

“I think they are going to be looking at this and . . . putting in place side-letters for new investments, saying, my capital will not be called down for investments in China in these three sectors,” Morrison Foerster’s Ellis said.

Others said geopolitical tensions, as well as China’s raids on the offices of due diligence firms and a crackdown on overseas listings which made it harder for investors to cash out, meant much damage had already been done.

“The bigger impact has already happened,” one adviser who specialises in raising money for private equity funds said. “US investors are not committing to new opportunities in China anyway.”

[ad_2]

Source link