[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday

Compliments of the season, and welcome to the first Trade Secrets of 2022. First of all, our format is changing as of today. Instead of a four-day-a-week newsletter I’ll be writing a comprehensive briefing on Mondays and a midweek opinion column. The content will be similar to before but the views even more trenchant. As ever, I’m open to helpful tips, lavish praise and gratuitous abuse, all of which can be directed to me via email — alan.beattie@ft.com. Today’s main piece looks ahead to the rest of the year and concludes that, whatever your idea of normality is, we’re probably not going back to it.

We want to hear from you. Send any thoughts to trade.secrets@ft.com or email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

Globalisation is surviving a hostile environment

My last set of year-ahead predictions, in 2020, had such a high hit rate I’ve been reluctant to repeat the exercise in case the massive role of good luck on that occasion became too obvious. In any case, globalisation since the pandemic hasn’t mainly been framed by a set of neat processes (trade deals, dispute settlement cases) with clear observable outcomes. So instead of spuriously precise forecasts, here’s what I’m keeping an eye on in 2022.

-

Supply chains are a wait-and-see puzzle. The jury’s still out on the culprit for the biggest problem in world trade right now, the supply chain disruptions that have persisted for several months. I remain pretty convinced by the arguments of members of the optimistic Team Temporary Rebound In Consumer Durables Demand rather than the gloomy Team Enduring Supply-Side Rupture. But I admit that my hopes about an easing in shipping and supply chain congestion towards the end of last year proved a bit premature.

Even if you mainly believe the demand-side thesis, the Omicron coronavirus variant has obviously interrupted ports, manufacturing and food supply across the world. By the middle of the year, assuming the Omicron wave has subsided somewhat, we should have a clearer sign of how deep-seated the problems are.

-

Brace yourselves as governments come to the “rescue”. The longer that supply chain problems persist, the more political chuntering there will be about industrial policy and the greater is the chance of truly boneheaded government interventions such as a global subsidy race for semiconductor production. The best thing governments can do for globalisation in the short term isn’t so much in trade policy as in macroeconomics and public health: keep domestic demand humming and people vaccinating and masking up.

Still, longer-term challenges such as climate change and tech rivalry will keep permanent pressure on governments for an activist trade policy. One example: the Biden administration’s response to the EU’s carbon pricing plan has been to suggest an anti-China managed trade alliance of dubious effectiveness and legality, and throw in some domestic favouritism on electric vehicles to boot. China hasn’t cut itself off from the world, but it is set on its China-first “dual circulation” course. Economic nationalism is getting contagious.

-

Big-power strategic rivalry and the Asia-Pacific. Everyone agrees that a dominant role in the Asia-Pacific region is the big prize in trade governance, but the US’s efforts at leadership are looking pretty feeble. The Biden administration has signalled it will continue to flail about trying to make Donald Trump’s deal with China work. In lieu of joining the CPTPP (Comprehensive and Progressive etc, you know the one) the US is coming up with what seem likely to be flimsy, face-saving bilateral memoranda with some of its members. Despairing of a strong US presence, America’s allies in the region (Japan, Australia, New Zealand et al) will agonise about how much they can slow-walk China’s application to join the CPTPP. The strategically autonomous Europeans have been presented with an early test of their resolve for a more geopolitical trade policy in the form of China’s bullying of Lithuania. It will be a huge challenge for the EU to weave trade into a coherent and durable strategic approach, even with the energetic French running the show for the first six months.

-

There aren’t many big trade deals on the table. There’s not much to rival CPTPP in terms of formal agreements involving the dominant trading powers. The big EU-US irritants, including Airbus-Boeing and the steel and aluminium dispute, have been patched up, but there’s little sign of any transatlantic substance beyond that. Apart from knocking off pending deals with New Zealand and Australia in the second half of the year, the EU is mainly focusing on arming itself with more bilateral tools against what it considers unfair competition. December’s World Trade Organization ministerial, postponed because of Covid-19, will reconvene at some point, probably towards the middle of the year. But even if it is deemed a success it probably won’t be in the top five, maybe the top 10, most important things to happen in global trade. The US is reluctant to commit to a major revival of the WTO before November’s midterm elections.

-

The UK has teed up its annual capitulation to the EU. I have one solid prediction for 2022. The UK’s new year tough talk to the EU over the Northern Ireland protocol will end in meek retreat. It always does.

-

What form of globalisation can survive? There are too many sustained disruptions to the trading system — climate change, data wars, tech rivalry, cyber security — for the pandemic to be a shock that simply goes away and lets normality return. Yet despite everything I’m pretty optimistic that the 30-year expansion of globalisation, which has weathered multiple shocks, will continue to resist implosion. The question is how it will adapt to stay alive.

Charted waters

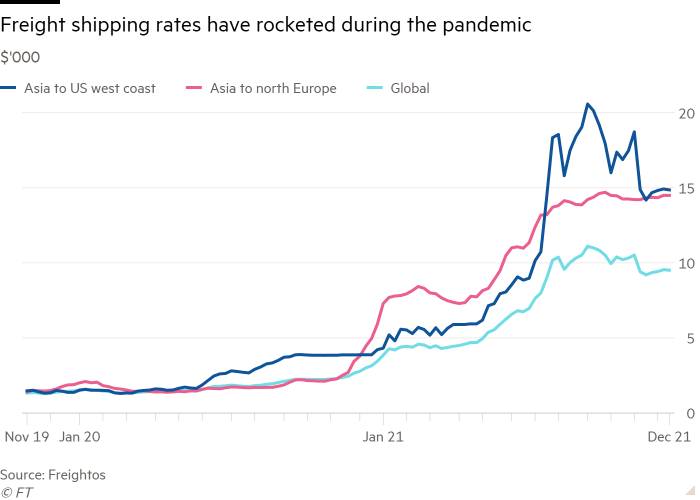

The following chart — pulled from the excellent Big Read yesterday on the supply chain crisis by Harry Dempsey — highlights how far freight shipping rates have risen during the pandemic.

In the decade prior to coronavirus, shipping cargo in containers was so cheap that the industry, plagued by excess capacity, struggled to make a profit, according to the piece. Some carriers went bust and the market consolidated such that the world’s leading nine carriers now control 83 per cent of tonnage.

As this chart shows — and has been noted previously by this newsletter — there are signs that shipping rates have fallen recently, at least on the more popular routes. However, there lingers an expectation that the world will have to learn to live with lofty freight rates and this feeds into the economic debate about inflation, given the link between shipping costs and the final price of goods.

Trade links

The New York Federal Reserve has designed a new index of pressures on global supply chains.

Shipping industry experts tell the FT the supply chain disruptions are likely to persist this year.

The former EU trade commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom optimistically suggests that the EU (which we note borders the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans) should join the trans-Pacific CPTPP.

Noah Barkin, of the German Marshall Fund think-tank, describes how German industry has mobilised to defend its close trade relationship with China in the face of scepticism within the new government in Berlin.

France’s official programme for its six-month presidency of the EU Council of member states emphasises the need to create an anti-coercion tool to deter bullying by other trading powers.

[ad_2]

Source link