[ad_1]

(Bloomberg Opinion) — Endorsing a big brand in return for cash is so last year. Now celebrities are clamoring for equity in the companies they’re promoting, in the hope of a bigger payday.

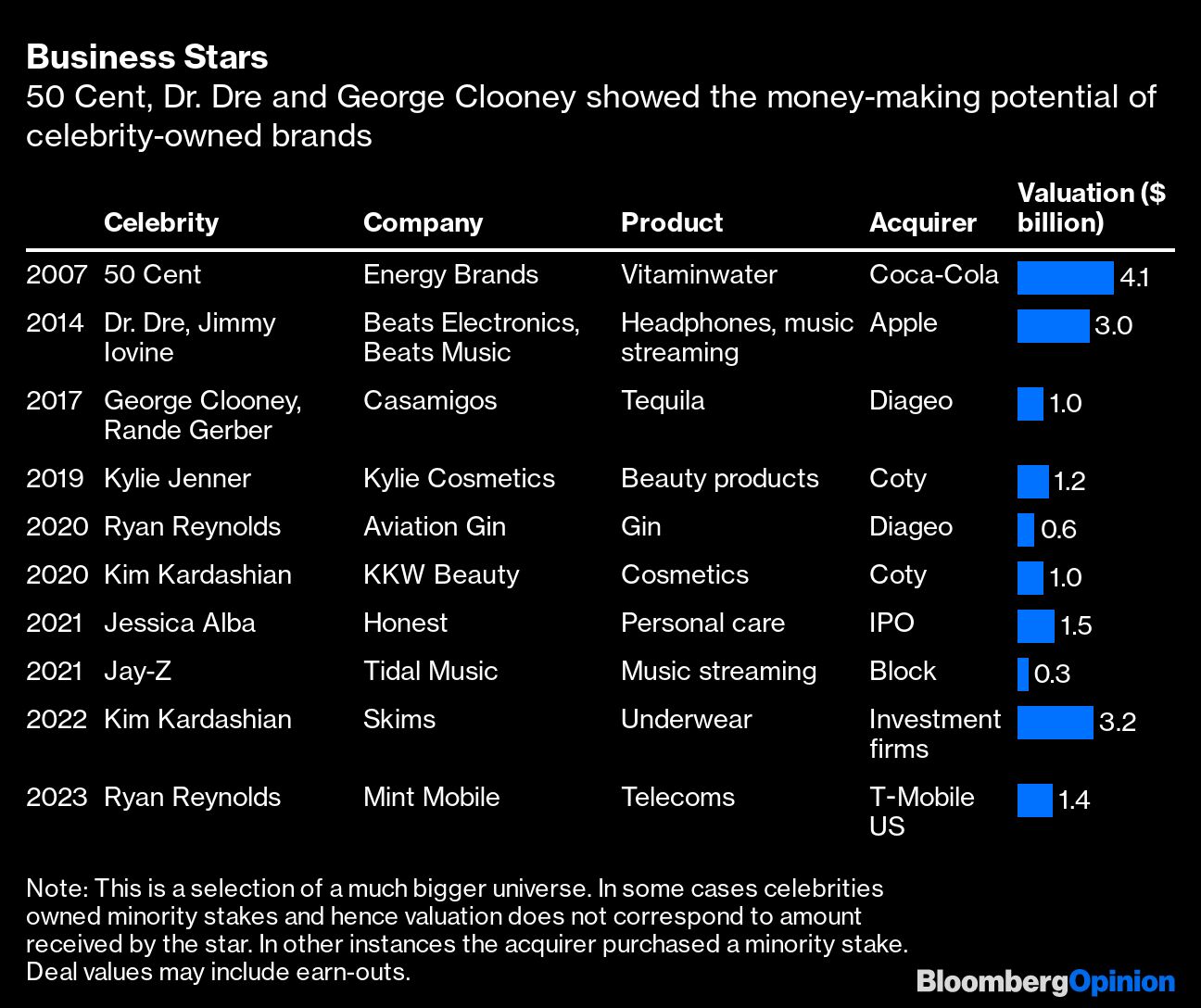

In short, everyone wants to be Ryan Reynolds, the Canadian actor and business mogul who sold his Aviation Gin brand to Diageo Plc in 2020 for $610 million only to trump that this month with the $1.35 billion sale of Mint Mobile to T-Mobile US Inc.

While it pains me somewhat to watch a handsome, kind and humorous actor/family man become astronomically wealthy from side hustles — has he no flaws? — it’s a trend both consumers and the business world should welcome. When stars have skin in the game, they are more discerning about the products and services they promote, and they work harder for brands for a lower upfront cost.

Equity is no guarantee of success, though. Seeming authentic while hawking a product isn’t easy and consumers are apt to lose interest unless constantly delighted.

The rise of celebrity entrepreneurs stems from a broader melding of finance and entertainment. Los Angeles has become a vibrant financial center and is home to startups like Snap Inc. Stars make fortunes at a young age and then need to diversify their wealth.

Hip-hop greats like Jay-Z and Dr. Dre popularized hustling, while Ashton Kutcher gained more credibility with his startup investments than via modeling or acting. Talent agencies have set up venture capital arms, while celebs like Kim Kardashian own private equity firms.

Most importantly, social media has given celebrities direct access to consumers, and vice versa. Of course, the results can be disastrous: Kanye West’s antisemitism left Adidas AG sitting on more than $1 billion of dollars of unsold Yeezy merchandise (the rapper is now known as Ye); last week, the US Securities and Exchange Commission fined a catalog of celebs, including Lindsay Lohan, for touting crypto without disclosing side-payments.

Celebrities crowding into endorsement opportunities can signal a bubble. In 2021, everyone wanted on the special purpose acquisition company bandwagon; now there are hundreds of celebrity wines and spirits. “The market currently has an oversaturation of celebrity alcohol brands, particularly tequilas,” says Mo Mostashari, president and co-founder of AMIBA Consulting, which facilitates celebrity partnerships.

Nevertheless, entertainers are natural storytellers. Providing they can find a good fit — ideally something off the beaten track as Reynolds did with low-cost telecoms or Kerry Washington’s advisor role arranged by Mostashari for teeth-aligner company Byte (recently acquired by Dentsply Sirona Inc. for $1 billion) — an equity deal can be a win-win. The hard bit is convincing people you’re not just in it for the money.

“Consumers and fans are highly discerning and can easily identify insincere brand endorsements,” says Mostashari.

Calling for a ban on celebrity fragrances before launching your own (ahem, Adam Levine) or professing not to care about beauty products and then pitching a $97 eye cream (Jared Leto) won’t work. Matt Damon’s “Fortune Favors the Brave” Crypto.com hucksterism belongs in the same bucket.

“If you look at Reynolds, or someone like The Rock, they make this a part of their life, you don’t think they are just shilling a product,” says Doug Shabelman, CEO of Burns Entertainment, a marketing agency.

Notwithstanding Reynolds becoming co-owner of lower-tier Welsh soccer team Wrexham AFC in 2020, the Deadpool star’s underdog shtick may wear thin now that he’s well on his way to billionaire-status; Mint Mobile customers aren’t delighted about him selling out to an industry giant.

Study the reaction to his Mint Mobile and Aviation Gin advertisements, though, and you’ll see what Shabelman means. Reynolds’ ad agency, Maximum Effort, excels at viral marketing, cultural savvy and wry, self-deprecating humor. “Ryan is the only person who has the power to make me willingly watch ads,” wrote one Youtube commenter. “Ryan could sell air and I would buy it,” wrote another.

“Of course everyone wants in, but not everyone can do what Reynolds did,” Shabelman says. “It’s a mixture of his marketing and internet acumen, the industries he focused on, the people he hired, his believability and gravitas. Just having talent or a big name isn’t enough.”

Billion-dollar exits like those achieved by Reynolds, George Clooney and Dr. Dre, remain outliers and these deals typically require the star to retain an equity position or achieve specified sales targets to receive the full amount.

That’s sensible because celebrity-owned businesses often lack staying power. Beyonce’s Ivy Park streetwear collaboration with Adidas is poised to end after sales fell short of expectations, the Wall Street Journal reported this week. Rihanna’s Fenty ready-to-wear fashion line with LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE closed in 2021 less than two years after its debut.

The value of Jessica Alba’s Honest Co. has shrunk from more than $2 billion following an IPO in 2021 to a more modest $160 million after losses mounted and sales growth slowed (Alba owns almost 6%). Oprah Winfrey’s involvement in Weight Watchers also hasn’t panned out as hoped — WW International Inc. has fallen 95% from its peak in 2018 and is worth less than when she invested in 2015 (Winfrey offloaded part of her stake at much higher prices).

Most celebrities will therefore continue to insist on at least some element of cash compensation. But for wealthier stars and those with the right work ethic and marketing nous, equity offers a more binary outcome. In Hollywood, as on Wall Street, you don’t make Ryan Reynolds money without taking some risk.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN

To contact the author of this story:

Chris Bryant at [email protected]

[ad_2]

Source link