[ad_1]

This article is the latest part of the FT’s Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign

Money: it’s emotional. If I had to sum up the main lesson I have learned after many years writing about personal finance, this would be it.

I always try to break down the barriers that prevent readers from getting to grips with their money. The financial industry’s love of jargon and constant rule changes from politicians do not help, but when you’re busy earning money, it’s easy for looking after it to slip down your list of priorities.

However, the biggest barrier is more likely to be lurking inside our heads. Our emotional relationship with money can make or break our financial success.

Earning lots of money or being born into a wealthy family doesn’t automatically make you good with money — in fact, the reverse is often true.

Mastering this emotional relationship is the key lesson in my forthcoming book, What They Don’t Teach You About Money, designed to set people who feel they know little about finance on the path to success.

Certain things matter a lot — including developing a long-term mindset, helping your children learn better financial habits and arguing less about money with your partner.

Memories are made of this

The money associations we form in early childhood remain a powerful influence throughout our lives, guiding our spending, saving and attitude to risk in ways that we might not even realise. Our parents have the biggest influence, but levels of financial knowhow vary drastically, and families are often very secretive about money.

Academic studies have found our emotional relationship with money is largely set by the age of seven. Not seventeen — seven!

A 2013 study by Cambridge university and the UK’s Money Advice Service found that key financial habits such as saving money and the ability to plan ahead are formed in early childhood, and have a lasting influence.

Developing early the perception that money is a limited resource can be very valuable. However, many adults’ aversion to dealing with numbers (and by extension, money matters) dates back to painful memories of school maths lessons.

People who consider themselves “bad” with money often think that earning more will be the answer to all of their problems. It might help, but it won’t address the underlying issues. This helps explain why so many lottery winners end up going broke, and the surprising number of people I’ve met who earn six-figure salaries yet have huge credit card debts and no pension.

To get a measure of their financial mindset, I ask every guest who appears on the FT’s Money Clinic podcast the following question: “What’s your earliest money memory?”

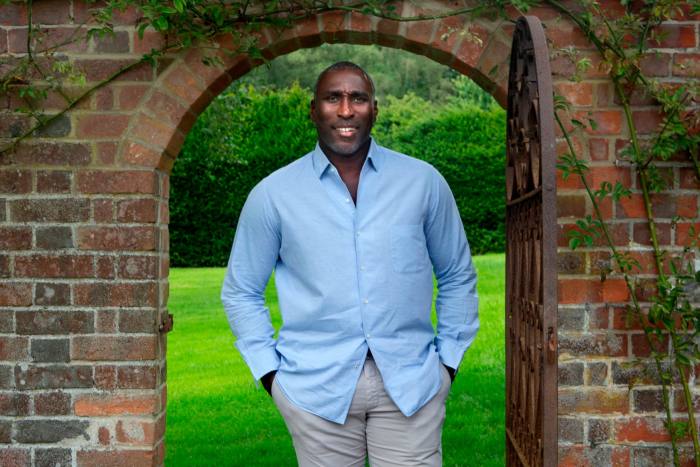

Sol Campbell, the football legend turned property investor, grew up in east London as the youngest of 12 siblings. He told me his earliest money memory was scouring the property pages of the local newspaper to see how much houses cost, as he dreamt of having the luxury of his own bedroom.

More recently, podcast listener Brooke told me how as a young girl in the US, the thrill of Black Friday bargain hunting with her mother helped sow the seeds of a damaging shopping addiction.

As for me, I vividly remember creeping downstairs at night as a young child to watch my parents managing their finances together around the kitchen table. Money was tight when I was growing up, but knowing that mum and dad were carefully budgeting made me feel secure. The fact that my mum, who stopped work to care for me and my brother, had an equal say in how dad’s wages were divided up also had a big impact.

In my book, I’ve come up with different “financial personalities” to help people explore what drives their money habits, and how ingrained patterns of behaviour can hold us back.

Like me, you could be a Goblin (a risk-averse cash hoarder) for whom inflation has been a wake-up call. I suspect some FT readers could be money-obsessed Spreadsheet Slaves — but do you control your money, or does your money control you?

It’s also possible you could be an Ostrich. Some people neglect money management through fear or anxiety, but in my experience, it’s often a lack of time. I once covered the story of a finance director of a listed company who had to resign after being declared bankrupt by HM Revenue & Customs — a fate he would have avoided if he had only opened the post!

Last year, at a talk I gave to a roomful of female accountants, one admitted to me afterwards she had received a tax bill after her earnings pushed over the £100,000 threshold (the point at which your personal allowance starts to be clawed back).

By sacrificing more of her salary into her pension, she could have avoided this, paying less tax and investing more for the future. Worse, she actually knew this, but was simply too busy to put the arrangements in place.

We schedule trips to the gym, hairdresser and dentist — so why not for looking after our money?

Family fortunes

Gaining a better understanding of what makes us tick financially is not only key to dealing with “bad habits” and making the most of our money, but also resolving conflicts. Having explored your own attitude to money, consider the role money plays in your closest relationships.

Vicky Reynal, a psychotherapist who specialises in helping people who have problems managing their finances, says all too often money isn’t the problem — it’s what it has come to symbolise in our lives. “Money is a powerful symbol, and one that people often use unconsciously to act out emotional issues,” she says.

Problems like overspending or being extremely risk averse might appear to be about money on the surface, but she says what is really being expressed are “our desires and fears around security, power, confidence, masculinity, femininity, control and love”.

Exploring this could help reduce the number of arguments couples have about money (see below).

In wealthy families, money is often used a proxy for power. They say “whoever holds the gold makes the rules” and indeed, it is common for money to be used as a means of controlling relationships (including from beyond the grave).

Intriguingly, wealth managers say the Covid pandemic experience has heightened the desire of couples to communicate and see eye-to-eye on their finances.

“Often, one person is the domestic finance ‘lead’ which could be the Mr or could be the Mrs,” says Emma Sterland, head of financial planning at Evelyn Partners, the wealth manager. “Now everyone can be on a video call, more couples attend meetings with advisers together. Even if one half of the couple is less engaged, at least they are there.”

The ability to explore and plan for future desires is key. Jason Butler, the FT columnist and former wealth manager, carries out a windfall exercise with couples he works with, challenging them to discuss what they would do if they unexpectedly came into £1,000, then £10,000, £50,000 and £100,000 to help stimulate conversations.

“Once you get past about half a million, it really blows people’s brains,” he says. The next step? Using these bigger picture goals to build your own long-term financial plan.

Passing it on

The money lessons in my book are aimed principally at 18-40 year olds who have inherited little in the way of cash or money management skills from their parents.

The sad truth is that we spend more time teaching children how to swim than to manage money.

As a trustee of the FT-backed charity Flic (the Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign) I think offering decent financial education in schools and beyond is the very least we can do to ensure future generations are equipped with these valuable life skills.

You might think wealthy families would have fewer problems — but they can be extremely secretive about money.

Wealth managers have a vested interest in helping to educate the next generation (after all, their clients’ children could be a valuable source of future fees) so they get to observe this at close quarters.

Sterland says affluent families tend towards two extremes — either keeping their children totally in the dark about money, so they struggle to understand the basics as adults, or revealing too much too early, which impacts their future life aspirations (I’ve previously called this malaise “rich kid-itis”).

“The hardest journey is for those who don’t get any exposure to financial decisions of any type,” she adds. As soon as they hit 18 and are offered overdrafts, credit cards and buy now pay later deals, disaster can result.

Cash-rich but time-poor parents who say “yes” to every want, guiltily buying all manner of gifts and treats for their children, normalise unhealthy spending habits.

Sterland’s two daughters, aged 8 and 6, do simple chores to earn pocket money, which they get to spend on pretty much whatever they want.

Please join FT consumer editor Claer Barrett and guests at FT FLIC’s online webinar Four Things Women Need to Know About Money in all Relationships, on Thursday March 8 at 1300-1400 GMT

“In our cashless society, it’s interesting how much longer decisions take if they’re spending their own money rather than waiting for mummy’s card to be tapped,” she says.

Learning from our own early money mistakes can be a powerful lesson. So too is the power of saying “no”. Knowing the difference between needs and wants is a core budgeting skill.

If your child is into gaming, you might have linked your own credit card to cover the frequent need for in-app purchases. But if they’re just clicking and spending there’s no perception that this comes at a cost, and no lessons learned about the value of money.

Learning to set boundaries is a habit that will grow, and help them avoid “lifestyle creep” later in life.

Butler commonly encounters 20 and 30 somethings “who are earning a lot, but spending a fortune” and unable to generate a surplus to be saved. “If they’ve been brought up in a free-spending environment, their money thinking never matures,” he adds.

The money conversation

When thoughts turn to estate planning, parents often fret about what age to conduct “the big reveal” as they fear their adult children will act like lottery winners.

Sterland suggests using Junior Isas to teach the basics of investing gradually from a young age, but notes how some parents avoid these as children get total control when they turn 18.

“It’s really important that coming into this money isn’t a shock,” she says. “If you don’t trust your teen to manage tens of thousands in a Jisa, how well prepared will they be for inheriting much larger sums?”

I save £50 a month into a stocks and shares Jisas for each of my 7-year-old twin nephews, and recently told them so. They were fascinated, but understand the money is locked up until their 18th birthday, and that Auntie Claer is investing it to help it grow.

I’ve started chatting to them about what a company is, and how their investments in a global equity tracker give them exposure to big corporate names they recognise from everyday life.

Plus, I’ve been covertly boosting their numeracy skills by challenging them to work out how much all of those fifty pounds might add up to (I’m saving the lesson on compound interest for when they’re a bit older).

If your family is wealthy enough for employment to be optional, instilling a work ethic could be a big challenge.

Philanthropy is one solution. It’s notable how many successful people interviewed in the FT’s My First Million feature say they will give significant sums to charity rather than leave everything to their children.

Butler has worked with many family business owners who are striving not to raise “nepo babies”.

“The classic case is a mother and father who have built up a successful business from nothing,” he says. “They don’t want their kids to just become CEO. They have to work on the factory floor, learn to respect the staff and make tough decisions.”

By doing so, the parents haven’t just passed on the money, they’ve passed on the values underpinning how they created that wealth in the first place.

Understanding the emotional foundations that our own relationship with money has been built upon is the key to developing better habits and a lasting inheritance.

Tired of arguing about money?

Disagreements about money are a major factor in marital breakdowns — and nothing can damage your wealth like divorce!

Common areas of conflict include how to merge your finances as a couple (and whether you should); one partner earning much more than the other; how couples approach financial decision making and how they respond to their children’s financial demands.

There could also be different cultural norms at play. For the English, talking about money is generally considered to be taboo, but other cultures are more open, and take a collaborative approach to supporting other family members.

Psychotherapist Vicky Reynal notes that people are more likely to be uncomfortable if the balance in their own relationship is different to the ones they grew up with, for example in incomes.

Making time to talk is half the battle, but she urges couples to approach conversations about money with a desire to understand each other.

“This is not just about you getting something off your chest and complaining,” she says. “It’s an opportunity for you to understand yourself and your partner better, but it’s also an opportunity to help your partner understand themselves better too. If you are just trying to convince the other that you are right and they are wrong, you will end up in a stalemate.”

Claer Barrett is the consumer editor of the Financial Times. Her first book What They Don’t Teach You About Money: Seven Habits to Unlock Financial Independence is published by Penguin on March 16 and is also available as an audio book. Claer will be talking about the book and taking questions from readers at a free FT online event at lunchtime on Friday April 21. To register to watch, go to FT.com/moneyevent

[ad_2]

Source link