[ad_1]

Big investors are wading back into the bond market after this year’s historic sell-off, with fund managers favouring debt relative to other asset classes for the first time since the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

A broad gauge of fixed-income assets across the globe has lost 15 per cent this year as high inflation spurred interest rate rises in developed economies, by far the weakest performance in data stretching back to 1990.

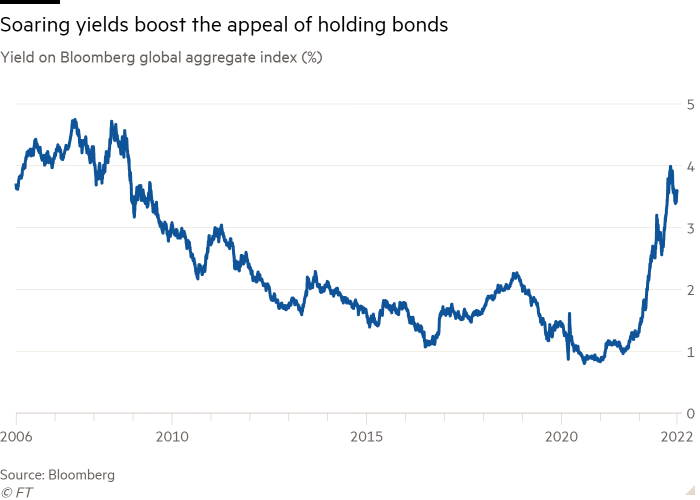

The resulting rise in yields is drawing in buyers who argue that bonds have not looked so attractive for years. The yield on the Bloomberg global aggregate index climbed as far as 4 per cent in October, up from 1.3 per cent at the start of the year and the highest level since 2008.

Investors are overweight bonds relative to other asset classes in their portfolios for the first time since 2009, according to the December edition of Bank of America’s monthly survey of fund managers who collectively oversee more than $800bn of assets.

But it is not only the prospect of actually receiving some income from highly rated bonds — an increasingly rare phenomenon over the past decade — that has rekindled interest in the asset class. Some fund managers argue that fixed income is set to regain its role as a portfolio ballast to riskier assets that rises as stocks fall — a typical correlation that vanished in the simultaneous sell-off of 2022.

“This year fixed income wasn’t a solution to falling risk assets, it was part of the problem,” said Antonio Cavarero, head of investments at Generali Insurance Asset Management. “But I think it can become part of the solution again, as long as the market is right and inflation continues to gradually come down.”

Cavarero said he had been buying European investment-grade corporate debt, which now offers a chunkier yield than the dividends on the region’s equities, and involves lending to high-quality businesses that should be able to weather the recession many economists see on the horizon. “You can have very solid expectations about your money coming back,” he said.

There are signs of a tentative move back into fixed income, after a flood of cash left the asset class earlier in the year: global bond funds had their first month of inflows in November after two months of outflows, according to EPFR data.

Most of the pick-up in bond prices has come since inflation started to cool in the US. But yields are now high enough to be attractive even if that tamer inflation swings higher again, according to Greg Peters, co-chief investment officer of PGIM Fixed Income. Spreads, or the premium investors earn to hold corporate debt rather than risk-free government bonds, have also increased since the end of 2021 — providing another incentive.

“With yields higher and spreads wider the starting point is the best that we have seen in a long time,” Peters said. “We are back to a more normal place.”

The fixed-income group Pimco said this month that the case for owning bonds was “stronger than it has been in years”, in part because of the asset class’s record of performing well during a recession.

A survey of economists conducted in December by the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business in partnership with the Financial Times showed that 85 per cent of respondents expected the US to enter into a recession next year. European economies, battered by high energy prices, are expected to suffer a deeper downturn.

Some investors including BlackRock have cautioned that in the next recession, highly rated bonds may not recover their portfolio diversification benefits. Bonds typically rise during recessions because investors move their cash into havens, but also because central banks respond by cutting interest rates to bolster the economy. But if inflation stays uncomfortably high during the downturn, the US Federal Reserve and its counterparts in Europe could be forced to keep rates high even in the face of rising unemployment and cratering growth.

“I don’t think the Fed will come to the rescue. They will have to stick to their guns. I don’t think they’ll be able to cut rates in 2023, contrary to what the market is expecting,” said Jean Boivin, head of the BlackRock Investment Institute.

Boivin believes inflation will fall, but remain far from the target rate, preventing central banks from relaxing monetary policy. For this reason, BlackRock is underweight longer-dated Treasury bonds, the part of the market that is particularly sensitive to inflation expectations.

“I have seen a lot of commentary saying ‘bonds are back’,” said Jeffery Johnson, head of fixed-income product at Vanguard. “But we would moderate that and say ‘bonds are better’.”

[ad_2]

Source link