[ad_1]

For the first time, women in Asia now hold more combined wealth than any other region except North America, and the total is growing faster than anywhere else.

Women in Asia (ex-Japan) will hold $27tn in wealth by 2026, $6tn more than women in western Europe, according to analysis done by Boston Consulting Group for Nikkei Asia. It found that women’s combined wealth in Asia overtook that of western Europe at the end of 2021.

Women in Asia have been adding $2tn to their collective wealth annually since 2019. This rapid clip is predicted to continue at least for the next four years at a compound annual growth rate of 10.6 per cent. The BCG analysis is based on financial wealth, including investment funds, life insurance and pensions, listed and unlisted shares and other equity, currency and deposits, bonds and similar financial assets.

The consulting firm excluded Japan from the analysis and said women there hold a much smaller portion of the nation’s wealth relative to comparable markets. It also said that women’s wealth in Japan is growing at a much slower pace of 2.6 per cent.

This is the first in a five-part series that will explore the drivers of this increasing wealth, the extraordinary progress women have made and the hurdles of systemic discrimination that remain.

This article is from Nikkei Asia, a global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective on politics, the economy, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and outside commentators from around the world share their views on Asia, while our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of 300 of the biggest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside Japan.

The series is reported primarily from Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam, as well as the US. (BCG’s analysis also included Malaysia, Myanmar, South Korea and Sri Lanka.)

From fighter pilots to professional cricketers, the series will highlight how women have made inroads in professions long dominated by men. It will lay bare the difficult fundraising journey of female founders seeking funding for start-ups. And it will look deeply at the advances and setbacks experienced by women in China, the world’s most populous nation that is often an outlier in data trends.

A Nikkei Asia analysis of men and women’s wealth, mined from the World Inequality Database, shows that the wealthiest top 10 per cent owns more than 60 per cent of the wealth, leaving roughly 5 per cent for the bottom 50 per cent. This is true of nearly all the countries in our focus, and the gap has been widening in the two most populous countries in the region, India and China.

An Oxfam study in 2016 showed inequality in the region to be deeply gendered. The richest people in the region are predominantly men, while women continue to be concentrated in the lowest paid and most insecure jobs.

In Asia, women are expected to accumulate 74 per cent of the wealth that men would accumulate at retirement, according to the 2022 Global Gender Wealth Equity Report.

The number of female billionaires in Asia increased from 13 in 2010 to 92 in 2022, according to a Nikkei Asia analysis of Forbes’ annual lists of billionaires.

Still, 75 per cent of women in the region work in the informal sector, where employment is often precarious, wages are lower, and there is no access to social protection. The gap is set to expand as the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic pushes more women and girls into poverty.

Over the past three decades, women’s share of labour income has been rising steadily in all the countries of our focus except China, according to a Nikkei Asia analysis of data from the World Inequality Database. In 1991, women in China accounted for nearly 40 per cent of the nation’s labour income. In 2019, that share fell to 33.4 per cent.

Women’s share of labour income varies widely across Asia, from 7.4 per cent in Pakistan in 2019 to almost 42 per cent in Vietnam. In south Asian countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, it is lower than in their south-east Asian and east Asian counterparts.

In south Asia, social forms of discrimination such as the caste system have also played a major role in worsening inequality. In India, for example, a woman is likelier to be poor if she is Dalit — formerly known as “untouchables”, who suffer the greatest socio-economic marginalisation under the centuries-old, descent-based caste system that structures Hindu society.

Caste privilege works through control of land, labour, education, white-collar professions and political power.

Other indicators of women’s economic empowerment include education levels, age of marriage and the number of children they have. In all the eight countries of our focus, women have been marrying later and having fewer children on average. A higher proportion has been pursuing education beyond high school.

But these developments have not translated to an increase in labour force participation in all countries. In China, women’s workforce participation has been falling steadily since 1991; India has seen a sharp decline since 2005. Overall, south Asia lags south-east and east Asia in labour force participation.

The disproportionate amount of unpaid labour performed by women also plays a crucial role in labour force participation. Across the world, women do 76 per cent of unpaid care work, dedicating more than three times the hours of men, according to a report from the International Labour Organization. In Bangladesh, women spend as much as six hours on unpaid work, while men spend less than an hour. Other south Asian countries such as India and Pakistan also have a wide gender gap when it comes to hours spent on unpaid care work.

Time-use surveys, which collate data on how individuals spend their time over 24 hours, are an important tool to measure the unequal burden of unpaid labour. But these surveys are laborious and expensive. Among the eight countries of our focus, Singapore has not conducted any, Indonesia has conducted only small surveys and Vietnam has conducted modular surveys that were not based on a 24-hour time diary.

Moreover, national-level data indicating averages can mask existing inequalities between socio-economic groups, according to research by UN Women. Poverty and location can lead to significant variations within a country.

In addition to the ability or opportunity to work and have an income, patterns of saving and investment also shape wealth accumulation, and determine the impact of financial shocks. In India and Bangladesh, most women rely on family and friends for emergency funds, while nearly nine in 10 women in Singapore rely on their savings, as do 60 per cent of women in Pakistan.

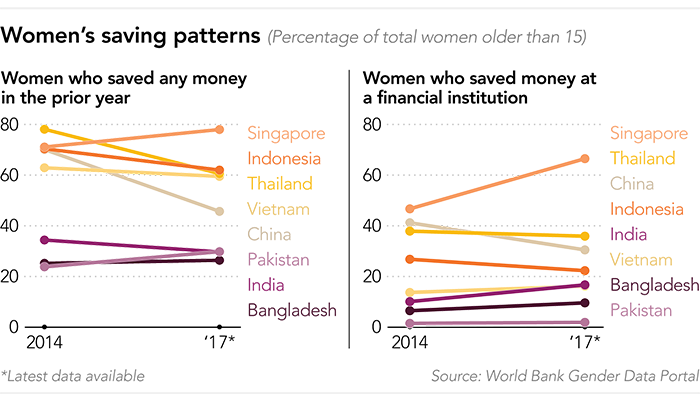

Patterns of saving also differ across countries, data from the World Bank show. Less than 30 per cent of women in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh saved any money over the year prior to a survey conducted in 2017.

In China, the proportion of women saving money fell sharply from 70 per cent in 2014 to 45.7 per cent in 2017. Declines were also reported in Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam. In Singapore, 78 per cent of the women reported saving money in 2017, up from 71 per cent in 2014.

But not all women save at financial institutions. In Singapore, two-thirds of women saved at one. In Pakistan and Bangladesh, the proportions were just 1.9 per cent and 9.6 per cent, respectively.

Over the next few weeks, our series will examine the increasing financial firepower of women in Asia, and the nuanced gender dynamics behind it.

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on December 5 2022. ©2022 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved

Related stories

[ad_2]

Source link