[ad_1]

The diktat came from Jamie Dimon during a closed-door meeting at JPMorgan Chase’s headquarters in November. Facing growing pressure from nimbler fintechs, the chief executive of the biggest US bank pushed the leaders of his two largest divisions to put aside any differences and collaborate on a new payments processing system.

“If I hear that any of you aren’t sharing information with each other, or you’re hiding information, you’re fired,” Dimon told the 15 or so executives who had gathered for the meeting in New York, according to two people with knowledge of the remarks.

Dimon’s pronouncement was delivered in his usual wisecracking style, but it reflected the challenges big banks face as they try to modernise their technology.

The new system being developed by JPMorgan’s corporate and investment bank — the CIB — would enable merchants to receive payments directly from consumers, cutting out the need for debit or credit cards and posing a threat to the lucrative fees earned by banks and dominant card companies Visa and Mastercard.

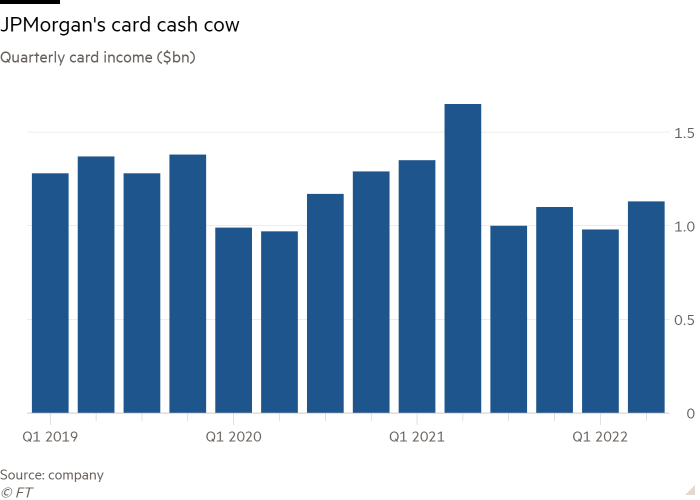

The belief in some parts of the CIB that this “pay-by-bank” product had the potential to supplant plastic created inevitable tensions with JPMorgan’s consumer and community banking division — the CCB — which booked more than $5bn in card revenues in 2021.

Dimon, however, reckoned it was better to risk existing revenue than to allow non-bank competitors to beat JPMorgan to the punch.

It had happened before: Dimon has said JPMorgan should have built its own mobile payments platform for merchants before Square, the fintech company co-founded by Jack Dorsey and now renamed Block.

“Jamie wants to understand products that could be threats to banking institutions,” said one person familiar with the project. “If [pay-by-bank] is going to be widely adopted, the bank needs to be there. If long-term it fails, it’s a bit of an insurance policy.”

Discussion at the six-hour event last November focused on how the many powerful internal interest groups inside JPMorgan would divvy up the pay-by-bank project. Executives in attendance included Daniel Pinto, the bank’s president and CIB head, as well as Marianne Lake and Jennifer Piepszak, who had recently been promoted to co-run the CCB, replacing the more powerful Gordon Smith in 2021.

Pinto and Smith had given the appearance of engaging in a friendly rivalry, joking at company events that their division was the bank’s biggest, while citing different metrics. The two also temporarily led the bank in 2020 after Dimon underwent emergency heart surgery.

When Smith left JPMorgan, Pinto became sole president. Whereas Smith had been on level footing with Pinto, Lake and Piepszak did not have the same title.

The emerging game plan was to have the CIB deal with the technology and build relationships with merchants, while the CCB worked to clarify customer protections in the event of misuse or fraud.

JPMorgan declined to comment on what happened at the meeting, which also touched on other payments projects at the bank.

Takis Georgakopoulos, JPMorgan’s global head of payments for CIB, said the bank had spent “a great deal of time” working on pay-by-bank through talking to merchants and understanding consumer protections.

“The relationship between the CCB and CIB is as close as it’s ever been. We all know that innovation in payments is one of the firm’s greatest opportunities and we’re committed to it,” Georgakopoulos told the Financial Times.

JPMorgan’s move into pay-by-bank responded to demand from merchants, such as Amazon and Walmart, chafing at banks and card companies hoovering up interchange fees that average 1.8 per cent per transaction in the US, according to payments consultancy firm CMSPI. In the EU, interchange fees are capped at 0.3 per cent for credit card payments and 0.2 per cent for debit cards.

Skimming a little bit from every card swipe adds up. In 2020, merchants in the US paid about $110bn in processing fees for $7.6tn worth of card transactions, according to the Nilson Report.

Pay-by-bank, which would enable sellers to take payment directly from a customer’s bank account, is part of the growing movement towards “open banking” — securely allowing consumers to give financial providers the ability to access their financial information.

JPMorgan already allows account holders to instantly pay one another through Zelle, a mobile application launched by the largest US banks in 2017. However, Zelle’s use for retail payments remains extremely limited. Bankers have said this is partly because it is run by a separate company owned by a consortium of lenders.

Bank transfer payments have caught on in countries such as the Netherlands and India, but US consumers have been slower to take it up.

This is partly because of the country’s clunky bank-to-bank automated clearing house, a network that settles payments in days rather than seconds and whose roots trace back to the 1970s. This may change next year with the US Federal Reserve aiming to launch FedNow, a new rapid payments service for big banks, and is another reason why JPMorgan is moving on pay-by-bank.

In the short term, JPMorgan believes pay-by-bank is an alternative for rent and bill payments as well as cash, high-priced debit and cheques, rather than for credit cards, according to people involved in the project.

In the longer term, however, the bank is making sure it is ready for the potential demise of credit cards.

JPMorgan is not the first to try and disrupt the credit card industry. In 2012, a consortium of major US chains, including Walmart, Target and Best Buy, tried and failed to get a product past a trial stage before selling it to JPMorgan in 2017.

Executives at the big card companies privately remain sceptical that pay-by-bank will dislodge credit cards in the US anytime soon, given deeply ingrained consumer habits, generous reward programmes and fraud protections that are more clearly defined than competing payment options.

But despite their confidence, card companies have taken steps to bolster their ability to facilitate direct transactions, including the recent acquisitions of fintechs Tink and Finicity by Visa and Mastercard respectively.

And banks such as JPMorgan — long incentivised to maintain the status quo since they accrue the bulk of interchange fees from card payments — are hedging their bets too, hoping pay-by-bank can replace at least some of those threatened revenues.

That is why Dimon stepped in and urged his teams to push past the tensions and pre-empt any disruption.

JPMorgan is now aiming to take pay-by-bank live next year and is in talks with at least one fintech company over a partnership to provide infrastructure support, according to people briefed on the plans.

The CIB and CCB are still collaborating on the project. In July, the bank held a “Senior Leaders Payments Offsite” where around 40 senior executives from the two divisions gathered at the posh Cipriani restaurant in Manhattan.

This time, Dimon did not feel the need to turn up, let alone issue any warnings.

[ad_2]

Source link