[ad_1]

In the era of automatic enrolment into workplace pensions, starting a new job usually means starting a new pension.

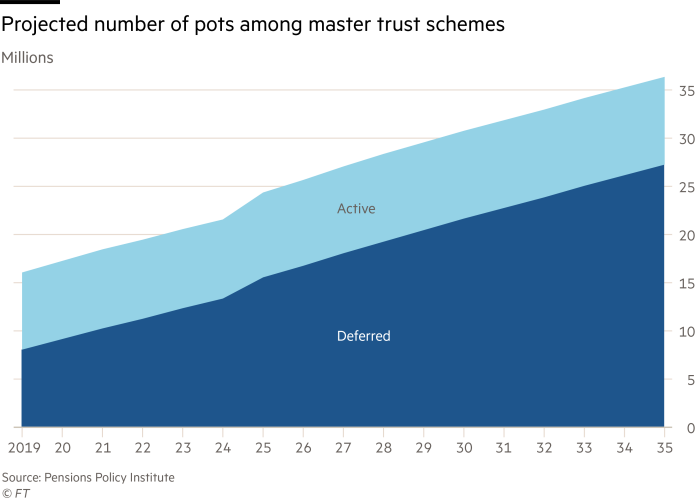

And with 7-8 per cent of us moving to a new job in any given year, we will soon see a proliferation of ‘deferred’ pension pots, those left behind when we change job and start a new ‘active’ pot.

Looking purely at master trusts, which are the dominant providers of workplace pensions in the UK today, the Pensions Policy Institute has estimated that by the mid 2030s there could be 27m deferred pension pots.

Where pensions are scattered, it can be hard for people to understand their overall position and to plan effectively. So there are often obvious advantages in bringing pots together. But what is less well known is that there are also potential disadvantages, notably in the loss of benefits attached to older schemes.

A worker in the UK today could easily have one or more ‘Defined Benefit’ pensions from previous jobs, some older Defined Contribution (DC) pensions taken out in the era before automatic enrolment started in 2012, as well as multiple modern DC pensions from recent jobs. In the future, workers could easily have half a dozen or more different pension DC pots across their career from different providers.

The government’s proposed pensions dashboard is likely to provide a huge impetus to consolidation, because people will see all of their pensions — including pots they may have lost touch with — in one place for the first time. There are also new firms entering the pension market actively promoting their services as a ‘consolidator of choice’ and offering a more user-friendly approach to pension saving.

While transferring out of DB pensions is regarded by regulators as unlikely to be in the member’s interest, the case for consolidation of DC pensions is much stronger, especially those taken out in an earlier era.

One of the strongest reasons for consolidation is to benefit from the typically lower charges associated with modern workplace pensions. All schemes used for automatic enrolment have a charge cap of 0.75 per cent a year for money held in their default fund, and the average charge is currently just under 0.5 per cent a year.

By contrast, an older pension could easily charge twice as much, in some cases reflecting the need to recover the costs of commission when the product was originally sold. Even apparently modest differences in fees can make a meaningful difference to the final size of a pension pot. We estimate that someone on average earnings saving through their life in a pension charging 0.75 per cent will end up with a pension pot around £37,000 larger than the same person facing a lifetime charge of 1.0 per cent.

But consolidation is not only about charges, it is also about investment.

If you have a pension, you are an investor and the most important choice all investors need to make is the balance between risk and return. With retirement savings scattered over multiple pots it can be hard to get an overall picture of what your money is invested in, still less to make sure that the combined investment mix makes sense.

Having money stuck in old pension pots can also mean missing out on the best practice in investment approaches. For example, old pensions may have more of a bias towards UK-based investments, missing out on the benefits of overseas diversification. Similarly, modern pensions are more likely to have an allocation to asset classes such as infrastructure that would have been less common in previous decades.

But, when it comes to consolidating pensions, it is important to pause for thought. It is crucial to fully understand what you are giving up before you transfer.

Older ‘legacy’ pension products may have valuable features that could be lost in the event of an individual pension transfer. One such feature would be a ‘guaranteed annuity rate’, which would be locked in regardless of prevailing market rates at retirement. With the past decade having seen a collapse in annuity rates, giving up a high and guaranteed rate on an old pension could prove to be a very costly mistake.

Older pension products may also have tax advantages that are no longer available. For example, they may allow you to take more than the current limit of 25 per cent in tax-free cash, or they might allow you to access your pension earlier than the normal minimum pension age.

Furthermore, many deferred pension pots tend to be quite small, and small pots attract certain privileges that would be lost in the event of consolidation into a single larger pot.

For example, someone flexibly accessing a DC pension pot worth more than £10,000, perhaps because of short-term financial pressure, could see their pensions annual allowance for future saving slashed from the normal £40,000 to just £4,000 (the so-called ‘Money Purchase Annual Allowance’) for the rest of their working life. But DC pots under £10,000 are exempt from this penalty, meaning consolidation might be a mistake for someone in this situation.

As our new paper demonstrates, there are many attractions to pension consolidation, and there is potential for both lower costs and a more optimal investment strategy. But those considering consolidation should ‘look before they leap’, making sure they fully understand the value of what they are giving up and not just focus on tidying up their pension affairs.

Sir Steve Webb and Dan Mikulskis are partners at LCP and authors of “Five good reasons to consolidate your DC pensions — and five reasons to be careful”, published August 2022.

[ad_2]

Source link