[ad_1]

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When the UK issued its first index-linked gilt in 1981, critics warned that a profligate government could store up problems for future generations.

That day might have come. Ahead of the Autumn Statement this week, persistently high inflation is expected to force the Office for Budget Responsibility to raise its March forecast for interest payments alone on these types of bonds by a third to £92bn over the next five years, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

This comes on top of the £89bn extra the OBR calculated in March that the government had spent on interest payments on these instruments over the previous two years, equivalent to 3.4 per cent of GDP.

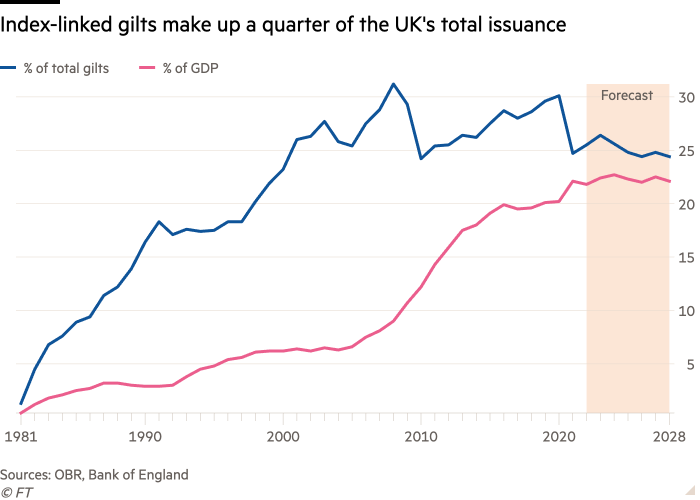

The UK now has about a quarter of its debt repayments linked to inflation, more than double the amount of Italy, which has the second highest proportion of any large economy at 12 per cent.

“This was the debt that people wanted,” said Lord Terry Burns, who was serving as chief economic adviser to the Treasury when the decision was taken to begin index-linked issuance.

Britain started down this path — previously seen as the preserve of crisis-prone emerging economies — more than 40 years ago out of desperation. Emerging from a severe inflation shock in the 1970s, the Treasury was quaking under so-called gilt “strikes” — repeatedly finding itself unable to borrow unless it raised interest rates sharply to lure investors back.

The then-Conservative government urgently needed to shore up confidence and establish its inflation-busting credentials. The thinking in the Treasury, led by chancellor Geoffrey Howe, was that investors would be attracted to bonds offering interest payments linked to rising prices because it would remove the incentive for the government to inflate down its debt.

Over time, so-called “linkers” became a much bigger part of the UK market than initially intended, as the Treasury became swamped with demand from defined benefit pension schemes eager to buy assets that would match their need to pay members in line with inflation. Britain’s large pensions sector has a higher proportion of these schemes than many other large economies.

“People were happy to pay up for them,” said David Page, an economist at Axa Investment Managers and a former official at the UK’s Debt Management Office, arguing that the way the UK regulated pensions “created a demand that couldn’t be fulfilled in other parts of the market”.

To an extent, officials took the view that it made sense to issue index-linked debt because there was a natural hedge in higher tax revenues when inflation was high.

When Labour came to power in the late 1990s, then chancellor Gordon Brown pursued a policy of ultra-long-term debt issuance by launching 50-year gilts, and ensuring a large chunk of those were indexed was probably necessary to convince investors.

Alistair Darling, Brown’s successor, told the Financial Times the Labour government felt vindicated in that approach as it meant that during the financial crisis in 2008 the UK had less debt to roll over than many other European countries.

Darling acknowledged “that landscape ha[d] changed dramatically” but added it was “difficult to say” if a surge of inflation was foreseeable.

Linkers have been particularly expensive in recent years because they track the flawed retail price index, which has consistently run at least 1 percentage point higher than the consumer price index. RPI peaked at more than 14 per cent last year and is still multiples above target at 6.1 per cent for the year to October.

“Things don’t always turn out the way that you want. The fact is that we held long-dated gilts and we were living in a low-interest rate environment and that meant that it was not a concern at the time,” Darling said.

But in 2017, after the OBR questioned the level of exposure, the government decided to limit the amount of new linker issuance, which had been running about 25 per cent per year of total new debt in the previous five years. This year, about 11 per cent of the issuance programmes are in index-linked debt.

The Debt Management Office has said it has no plans to reduce the proportion of index-linked issuance further but would instead review the situation annually taking into account market conditions. In absolute terms, it still plans to issue more index-linked debt this year than it did in 2022-23.

This policy reflects a view shared by economists and officials that the UK’s approach has probably paid off over time, despite the costs incurred as inflation soared.

Moreover, debt specialists argue that were the government to reduce the proportion of linker issuance dramatically in response to the high price environment, it would undermine the inflation-fighting credentials that the use of the instrument was meant to establish.

They also point out that if inflation is brought back under control, the longer average maturity of linkers — about 18 years compared with 13 years for conventional gilts — would mitigate the extra cost over the lifetime of the bond. “What feels like a painful bout now is just a blip in the 50-year life of one of the really long ones,” a Treasury official said.

But it is impossible to prove conclusively whether the UK’s decision to adopt index-linked gilts has paid off, although on balance, John Kay, one of the UK’s leading economists, believes it has.

“Over most of the time, inflation has been lower than people expected,” he said. “I suspect looking back since 1981 — the answer is it was cheaper to have issued index-linked gilts.”

[ad_2]

Source link