[ad_1]

The spectre of a wider conflict in the Middle East poses a fresh threat to the global economy just as the world emerges from shocks triggered by Covid-19 and the Ukraine war, finance ministers and officials have warned.

Broader regional tensions would have significant economic ramifications, they said, as they rounded off meetings of the IMF and World Bank in Morocco this week. The biannual events took place as Israel declared war on Hamas and launched a major bombardment of the Gaza Strip.

“If we are facing any escalation or extension of the conflict to the whole region we will face big consequences,” Bruno Le Maire, France’s finance minister, told the Financial Times, adding that risks ranged from higher energy prices stirring inflation, to a decline in confidence.

Kristalina Georgieva, the head of the IMF, warned of a “new cloud on not the sunniest horizon for the global economy”, encapsulating fears among the delegates in Marrakech that the medium-term prospects for the global economy are lukewarm.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan, called this “the most dangerous time the world has seen in decades”.

Heading into the meetings, officials had expressed relief that central banks had managed to curb inflation without provoking outright recessions — sidestepping a risk that the IMF flagged in April as it spoke of a possible “hard landing” for the global economy.

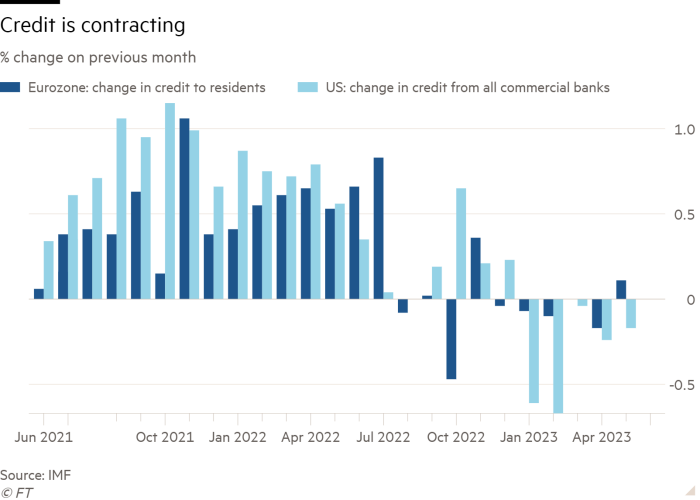

Central banks appeared to have tightened monetary policy, curbed credit growth, and cooled the labour market “without overdoing it”, said Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, the IMF chief economist prior to the event.

But, as delegates convened, the mood darkened as the wider implications of the Israel-Hamas war mixed with underlying anxiety about persistent vulnerabilities in the global economy. The IMF’s analysis pointed to worsening longer-term growth trends, as economies struggle to lift productivity, barriers to free trade mount amid worsening political tensions, and public debt rises around the world.

Notable in the IMF’s short-term forecasts — prepared before the violence in the Middle East broke out — was a lack of obvious bright spots beyond a handful of countries such as the US or India.

“There’s no accelerant here,” said Joyce Chang, head of global research at JPMorgan. “I don’t think anyone feels like there is a big catalyst over the next year or so.”

The key economic danger following the events of October 7, officials argued, was an escalation of fighting in Israel and Gaza into a wider regional conflict. This could not only hit confidence, but add a fresh inflationary outburst to economies that are only beginning to recover from a series of price shocks.

The IMF believes a 10 per cent rise in oil prices would raise global inflation by about 0.4 percentage points.

Gita Gopinath, deputy head of the IMF, said the world was facing “a large number of shocks” including the Middle East conflict and its potential implications for energy prices.

Gopinath added: “Debt levels are at record levels and at the same time we are in this higher-for-longer interest [rate] environment. There is a lot . . . that could go wrong.”

Paschal Donohoe, the head of the Eurogroup, told the Financial Times that the big economic question was over whether the conflict would have an impact on inflation expectations, and what that could mean for getting price pressures down in 2024. Europe will continue to grow as the conflict continues, he predicted, but at a lower pace than he had hoped for.

Janet Yellen, the US Treasury secretary, said she was sticking with her soft landing call, telling reporters this week she does not expect the conflict to be a “major likely driver of the global economic outlook”.

But officials stressed the conflict came at a time when the world economy was in a fragile state.

The global economy is now widely expected to grow at a relatively weak level over the medium term, coming in at just 3.1 per cent in 2028. That compares with a five-year outlook of 3.6 per cent growth just before the pandemic, and 4.9 per cent before the onset of the financial crisis.

More than 80 per cent of economies are now facing worse prospects from 15 years ago, according to the fund, for reasons varying from slower productivity to a slowdown in population growth.

Added to that is the fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs — a process that is difficult to reverse and made all the more likely by geopolitical tensions. The IMF estimated earlier this year that mounting trade barriers alone could reduce global economic output by as much as 7 per cent over the long term.

On top of that come rising fiscal risks, as the global public debt ratio climbs towards 100 per cent of gross domestic product by the end of the decade. This has revived concerns over debt sustainability at a time that Chang described as “inconvenient”.

Recent jitters in the world’s biggest financial market — US Treasuries — were driving up global borrowing costs just as central banks were shrinking their balance sheets, and government debt issuance was on the rise, she explained.

Speaking at one of the final panels of the annual meetings, Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, underscored just how tricky a set of circumstances these headwinds posed.

“There are all these balls in the air,” she said. We are not exactly sure where they are going to land.”

Additional reporting by Martin Arnold in Frankfurt

[ad_2]

Source link