[ad_1]

The prospect of a Conservative plan to shake up the inheritance tax regime emerged this week as the FT reported that Downing Street aides had debated reducing or scrapping the levy to shore up voter support ahead of next year’s general election. FT Money looks at how the UK’s inheritance tax system compares with other advanced economies.

Low proportion pay IHT

Inheritance tax is often selected as the “most unfair” tax in opinion surveys. Dawn Register, head of tax dispute resolution at BDO, an accountancy firm, thinks this is because “there’s a lot of emotion around [IHT] as it’s linked to someone’s death”.

Nevertheless, very few people in the UK will ever pay it. Latest figures show that less than 4 per cent of estates will be liable for IHT. According to OECD data, the UK has one of the highest IHT exemption thresholds, with only Italy and the US — where 0.2 per cent of estates pay tax — higher. In contrast, in Belgium, 48 per cent of inheritances attracted taxes, the OECD found.

The UK is also one of only three countries, along with Denmark and the US, that tax the estates of deceased donors. Other countries tax the recipients.

Several OECD countries do not have inheritance taxes, including Australia, Austria, the Czech Republic, Canada, Israel, New Zealand, Norway, Slovak Republic and Sweden. They mostly abolished their inheritance taxes decades ago — in an era when lowering taxes was popular — with several ditching the levies before the financial crisis hit. Only Czech Republic and Norway abandoned the taxes more recently, in 2014.

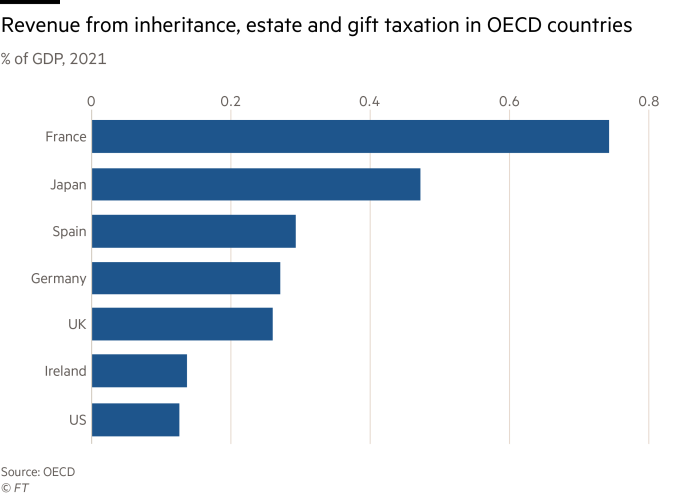

Countries that do tax inheritances only collect a small portion of total tax revenues from the levies. OECD research showed that revenues from inheritance, estate and gift taxes exceeded 1 per cent of total tax in only four OECD countries: Belgium, France, Japan and South Korea.

In the UK, inheritance tax receipts are forecast to be around £7bn this tax year, representing just 0.7 per cent of tax collected, according to a report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies this week. This puts the UK at the middle to higher end in terms of revenue collected as a share of total tax receipts, though revenue is just one of the ways of assessing how effective the tax is.

“Curiously we don’t sit badly in terms of how much money we raise [from IHT] compared with other countries although it is still not a lot,” says Emma Chamberlain, a barrister specialising in inheritance tax and trusts. “But there’s no doubt in my mind that it’s an unfair, arbitrary and over-complex tax. People whose main wealth is tied up in their house can effectively give far less away in practice than those whose wealth is more liquid.”

She argues there are many reasons for this. “I think the absolute killer on IHT is the flat rate, it’s high at 40 per cent,” she says. “As soon as you have high rates, you have lots of reliefs and then you get unfairness, avoidance and lobbying [for more exemptions].”

High rate

The UK’s headline rate of 40 per cent on inheritance tax is high internationally.

OECD research also reveals the UK is unusual in applying flat rates to inheritance taxes. Fifteen OECD countries it surveyed applied progressive rates — where the tax rate rises with the value of the inheritance — up to 80 per cent in the case of Belgium. In contrast, seven countries, including the UK, levy flat rates. The UK had the joint highest flat rate of tax of 40 per cent, shared with the US.

In practice, the ability to claim allowances and reliefs means the average effective tax rate — the rate that estates actually pay — is much lower, at 13 per cent, according to data from HM Revenue & Customs. But Chamberlain says people “don’t see it that way”, even when the difference is explained to them. People “resent” a 40 per cent rate and are more likely to try and avoid it than if it were around 20 per cent, she believes.

Dan Neidle, a tax lawyer and founder of Tax Policy Associates, says the UK’s inheritance tax system suffers from an “unfortunate combination” of a high rate “which makes it unpopular and motivates avoidance” and “overly generous exemptions (which enable avoidance)”.

“Denmark, the Netherlands and Germany all collect about the same amount of tax as us, but with markedly lower rates,” he adds.

‘Not progressive’

By tightening reliefs and exemptions, Neidle argues the UK could create “a fairer, more effective” inheritance tax system by using the money collected from a less generous relief regime to lower the rate.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies this week recommended the UK government abolish the “special treatment” given to business assets, certain types of shares, agricultural assets, pensions and homes passed to direct descendants.

David Sturrock, a senior research economist at the IFS, says: “These exemptions and reliefs open up channels to avoid inheritance tax. This is costly, unfair and distorts economic decisions. Reforming them could raise as much as £4.5bn in additional revenue.”

Neidle adds that the IHT exemption for the foreign property of UK residents who are non-domiciled should be tightened. This exemption is supposed to lapse after 15 years, when the person becomes domiciled in the UK. However, if individuals put non-UK assets in a trust before that point the assets can remain permanently free of IHT for their descendants.

Other advisers told FT Money they had seen the exemption used so that huge sums were transferred with no inheritance tax charged.

“A tax that’s very progressive in theory, turns out to be only progressive for the upper middle class — who are rich enough to get taxed, but not rich enough to avoid it,” says Neidle.

“The middle class pay nothing (unlike much of the Continent). The seriously wealthy pay (relatively speaking) considerably less than the upper middle class.”

[ad_2]

Source link