[ad_1]

The top search suggestions on YouTube for videos with the prompt “Chinese economy” include: “is about to collapse”, “is 60 [per cent] smaller than we thought”, and, simply, “is done”.

China-bound investors using the site to do some due diligence would be overwhelmed by bearish views and have to look hard for a bull.

The rise in amateur doomsayer analysts on China on sites such as YouTube and Reddit echoes the negative opinions of many professional investment advisers.

It has helped drive an exodus of foreign financial investment out of China. In August alone, foreign investors (including institutions) dumped a record $12bn of stocks listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen, more than any time since the launch of the stock connect scheme in 2014.

Retail savers are active in the exodus. In the UK, the Investment Association, the trade body, says they have been withdrawing money from China funds on a net basis for the past five years.

IA figures suggest that UK investors now hold less of their individual savings accounts — a key retail savings vehicle — in China-only funds than they do in India-only funds, even though India’s economy is a fifth of the size.

Fears of arbitrary political crackdowns on Chinese companies and sectors, worsening geopolitical tensions between the west and China and a lack of trust and transparency in the Chinese economy have put off many investors.

The economy has also run into some serious economic turmoil: growth has slowed, the debt-laden property sector is in crisis and the government is hesitant to launch a full-scale stimulus programme to reverse the effects of the country’s disruptive zero-Covid policy.

FT Money examines whether China is still a land of opportunity for foreign retail investors. If it is, what should savers buy? If not, how can they build a globally diversified equities portfolio without the world’s second-largest economy?

Can the dragon ride high again?

The bull case for Chinese equities is simple — just look at the long term. China’s growth rate from 2000 to 2022 averaged 8 per cent. Even now, as China faces difficulties, the IMF estimates that the country will still generate some 35 per cent of global growth this year.

It has 12 of the world’s 100 largest companies by market capitalisation, according to Bloomberg. Its companies are poised to dominate new industries such as electric vehicles, batteries and electronics. With 1.4bn people, it has the world’s second-largest population after India and a fast-expanding middle class.

Bullish analysts believe short-term headwinds do not negate the opportunities. “With a large population, rapidly growing middle class, and ambitious economic reforms, China offers a compelling opportunity for investors,” says Joe Hills, lead investment analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown.

“The country is positioning itself as a global leader in various industries, from ecommerce giants and renewable energy to advanced manufacturing and artificial intelligence. With careful research, understanding of local dynamics, and a long-term perspective, investors can tap into the enormous potential that China offers.”

Investors who remain bullish on China claim that the current economic slowdown is cyclical, not structural, meaning that at some point growth will return to impressive levels. Beijing has set an official target of around 5 per cent growth for this year, although most major global banks now project that it will underperform this by up to 0.5 percentage points.

A recent analyst note from Bank of America supports this thesis, claiming that cyclical forces holding back the Chinese economy do not mean its growth potential has “collapsed”.

The bulls believe that while a wholesale US-style stimulus package is unlikely in China, the government will unveil targeted measures, following the recent selective interest rate cuts. Alice Wang, China portfolio manager at Quaero Capital, says: “Many investors assumed it was going to be a giant national package like the US. But I think the Chinese government does have the capability to do targeted stimulus for cities and industries that need it.”

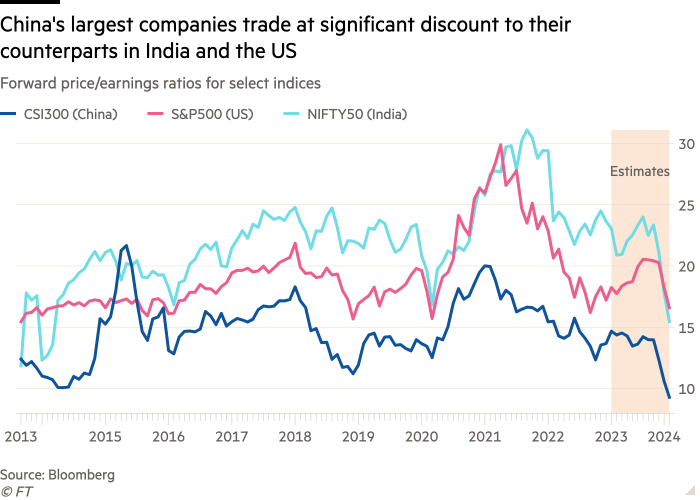

Goldman analysts note that Chinese equities are now historically cheap. The MSCI China index and the CSI 300, the largest China A share stocks, trade at “suppressed valuations” in price/earnings terms — below both five-year averages and, respectively, at 40 and 30 per cent discounts to the average of developed market and non-China emerging markets.

Or has the dragon lost its fire?

But the bears too have a strong story. Long-term structural weaknesses of the economy are well known to retail investors and YouTube watchers alike. The country is no longer reaping a demographic dividend and the ratio of workers to dependants will only worsen, stifling productivity and redirecting spending priorities.

The country is also transitioning from a low-cost manufacturing hub to a higher-value producer as wages rise and assembly factories move to lower-cost countries such as Vietnam and India. This has been worsened by “friend-shoring” and “nearing-shoring” trends where Western companies shift their supply chains out of China.

Analysts say that the years of infrastructure and property-fuelled growth are over, as the property market is more saturated and the marginal returns from new public infrastructure are lower.

“I think China has fewer tools in the bag to do this massive stimulus,” says Vivian Lin Thurston, portfolio manager at William Blair. “A big stimulus would be like a drug that helps in the short run but might worsen structural issues like the property sector in the long run.”

International investors are voting with their feet. A recent Bank of America survey of 258 money managers with $678bn in assets under management found that a third of fund managers believed the Chinese commercial real estate crisis was the biggest threat to the global economy. The survey recorded managers moving out of China and other emerging markets and into the US.

In the short term, many investors also fear politics. Sanctions levied by the US on China could hurt tech and manufacturing companies. Meanwhile, companies that find themselves on the wrong side of Chinese government domestic policies can see their share price plunge.

Most recently Beijing has launched an “anti-corruption” campaign on the healthcare industry, which has led to the CSI medical service index (healthcare stocks within the CSI 300) falling by 5 per cent since the start of July.

The policy shift from Beijing on the sector, in some part due to a suspicion that it overly profited from the country’s “zero Covid” policy for almost three years, mirrors previous crackdowns on the high-growth education and tech sectors that hit investors hard.

Even in more benign times, the Chinese stock market may have produced commercial giants, but it persistently lagged behind economic growth. Chinese nominal GDP in renminbi was more than nine times higher in 2022 than in 2002 but the CSI 300 index was less than 200 per cent higher.

This suggests that equity investors have not received the full benefit of the economic advance. There is indeed no automatic link between growth in GDP and the stock market in any economy. And in China it’s been particularly weak, given the high level of government intervention in the economy. Foreign investors, in particular, have had difficulty anticipating policy shifts — and are likely to remain so in the coming years.

How can bullish investors get China exposure?

Investing in China means getting to grips with listing jurisdictions. China A shares are mainland-listed securities quoted in Chinese renminbi. Retail investors can buy them through a stock connect scheme with Hong Kong. China H shares are Hong Kong-listed equities quoted in Hong Kong dollars.

Then there are Chinese companies listed abroad. As of January 2023, 252 Chinese companies were listed on the three biggest US exchanges. The largest of these is internet giant Alibaba.

If you want some China exposure without buying specific stocks, the simplest way is to buy the index. The CSI 300 is the 300 largest China A-share stocks by market capitalisation. The MSCI China is broader and includes H shares and foreign listings, as well as mid-cap companies.

Asset managers such as BlackRock offer low-cost access to the MSCI China index through their iShares ETFs. The Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 UCITS ETF offers a similar service.

But in the same way that “buying the S&P 500” now means in essence buying US technology companies with some healthcare and financial services names thrown in, these indices give greater weight to certain dominant sectors, such as consumer technology.

Investors wanting a more granular approach can consider separate sectors and companies.

One story that managers tell is of the Chinese consumer. Even if high tech companies such as Huawei run into problems with trade sanctions, they say, the growing Chinese middle classes with their rising incomes will continue to support domestic consumer companies, which also appear more insulated from the kinds of policy crackdowns that have hit tech, education and healthcare.

Names such as trip.com (formerly Ctrip), a travel platform travel, PDD, an ecommerce platform and Meituan, best known for its food delivery app, are often mentioned as defensive stocks that could do well as long as city dwellers have disposable income.

One other company of interest is Kweichow Moutai, maker of luxury grain alcohol baijiu, which is often seen as a proxy for business dealing in China given its consumption at official banquets. It has been at some points in the last decade China’s largest company.

Chinese technology stocks that are still able to excite include Tencent, which is China’s largest company by market capitalisation and runs the WeChat “superapp” that US billionaire Elon Musk is eager to imitate with his company, X.

In manufacturing, investor excitement focuses on China’s dominance of electric vehicles and battery production. This year the country is set to become both the world’s largest exporter of electric vehicles and of automobiles more broadly.

“We saw Chinese companies rise up very quickly to become leaders on a global scale, such as energy transition related industries like EV and batteries,” says Thurston at William Blair.

Certainly, there are risks: it is unclear, for example, what the impact will be of the EU anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese EVs.

But Jason Hsu, founder of Hong-Kong based quantitative asset manager Rayliant says that Chinese EV makers such as Warren Buffett-backed BYD, which makes both batteries and EVs, are “cost leaders”. “Imagine if you could buy Toyota in the 1980s,” he says. BYD stock is up 25 per cent year to date, at $65 per share.

Another name that attracts international attention is EV maker Xpeng, which in July received a $700mn investment from Volkswagen. It announced this month that it would start selling cars in Western Europe next year. The stock price is up 80 per cent this year, which might mean this opportunity has passed but others will emerge in China’s teeming EV sector.

Retail investors might also consider that when they invest in Chinese companies, they are not necessarily playing against big institutional money but Chinese retail investors. Research from CEIC and UBS from 2018 found that Chinese retail investors were responsible for 86 per cent of the trading volume of A-shares.

One result is that Chinese stocks are volatile, with animal spirits and online “pump and dump” schemes abounding. The government is moving to crack down on market moving “little essays” that circulate on social media.

But the upside of this phenomenon is that there is potential for smart investors to generate alpha by taking advantage of these sentiment swings, according to Hsu of Rayliant.

Actively-managed funds could be one way of playing this, such as Fidelity’s China Special Situations Investment Trust, which, as well as holding equities, holds illiquid names such as TikTok owner ByteDance and drone maker DJI.

Baillie Gifford, JPMorgan and Invesco all have China funds that are among the 10 most owned by retail investors on Hargreaves Lansdown.

Additional reporting by Louis Ashworth

What can bearish investors do?

For a start, you can stay away from China. That’s simple enough.

Sophisticated investors, with a risk appetite, could go one better — and short the market. They could, for example, consider the Direxion Daily FTSE China Bear 3X Shares, which offers the opportunity to make a three-times leveraged bet against the FTSE China 50 index. It is not for the faint-hearted.

“These [funds] are not buy-and-hold vehicles,” says Ed Egilinsky, managing director at Direxion. “They are designed for short-term trading . . . people trade off [negative] headlines about China.”

Retail investors who don’t want their money exposed to the China market’s tribulations, while still looking to capitalise on emerging market growth could look at other Asian states.

According to Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, India, the Philippines and Indonesia offer some of the lowest correlated returns in Asia to China, while still being rapidly growing economies with large populations.

Meanwhile, investors who want some exposure to China through indirect means might consider other emerging markets. Analysts at Robeco tracked the correlation of the Chinese constituents of the MSCI emerging markets index with those of the MSCI EM ex-China index; it now sits at about 50 per cent.

An even more straightforward way is to look at the many Western companies with significant interests in China. To name a few: Apple, LVMH and Unilever.

[ad_2]

Source link