[ad_1]

Receive free Gilts updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Gilts news every morning.

Bonds are back in vogue. Interest rate rises mean these securities offer the best returns in a decade. This week’s Lex Populi will shed light on why and how new investors can take advantage of this important asset class.

Bonds come in all shapes and sizes. But most of them are easily tradeable promises to pay the holder interest or “coupons” for a fixed period after which the borrowed sum — “the principal” — will be repaid.

The return the investor can expect to receive after buying a bond at a particular price is expressed as the yield-to-maturity or redemption yield.

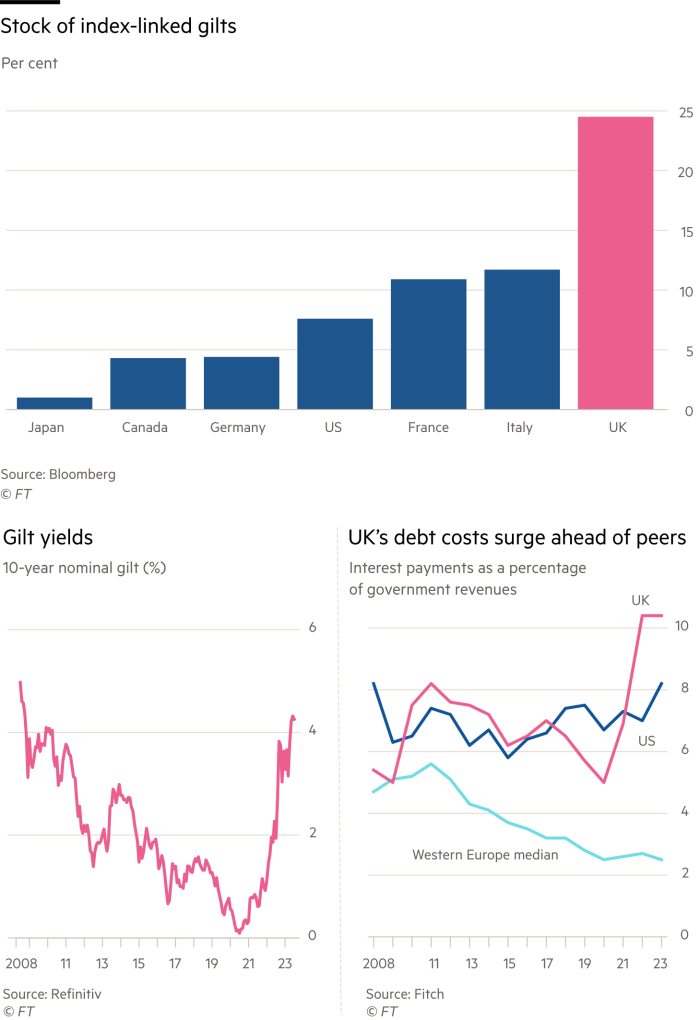

Take UK government bonds, known as gilts. When investors buy these, they are, however indirectly, lending money to the British government. Yields on gilts hit their highest levels since 2008 at the beginning of July. Ten-year gilt yields now yield about 4.2 per cent, up from just 1 per cent at the start of last year.

When a bond is priced at par or face value, the yield or coupon are both equal. But after gilts and other bonds are sold by the government, a portion of them trade in the secondary market. This is where investors’ expectations of inflation and interest rates impact prices and yields.

Gilt yields rise when prices have fallen. There is an inverse and proportionate relationship between the two. If you owned 10-year gilts at the start of last year and held on to them, you would have lost money. The declines averaged just over 20 per cent of the investment last year.

The reason is that the central bank, the Bank of England, has been raising interest rates in an effort to lower inflation. That lessens the attraction of any fixed income stream. Gilts’ coupons usually reflect the market interest rate at the time of issue.

This is where things get more complicated. Some gilts pay interest that varies in line with inflation. These “linkers” are the reason why the UK — which has issued large amounts of this debt — is set to make the highest interest payments in the developed world this year. Debt interest will be a tenth of government revenue, rating agency Fitch said this week.

In the case of linkers, the yield is what is called the real yield or the expected return over the life of the bond in excess of inflation, as measured by the Retail Prices Index. That is about 1 per cent on 10-year linkers today.

If you buy a gilt midway through its term, the amount you receive back at the end of its term will depend on whether the gilt was trading above or below “par” (face value) at the point of purchase.

Some gilts that are now in the market were issued shortly after the Covid-19 pandemic, when interest rates were at historic lows. Over the past year, rising interest rates have resulted in these trading at a significant discount to their face value.

Buying heavily discounted bonds can offer tax advantages. Much of the return comes from the difference between the purchase and sale price — or its maturity value. The absence of tax on capital gains is a big part of gilts’ appeal to high income investors.

UK retail investors have wide access to gilt markets today. They cannot participate in primary government issuance, as retail investors in the US can. But they can buy gilts exposure for a little as £1 through Hargreaves Lansdown which has access to a wide range of maturities, including index-linked gilts.

Unless you have a very large sum to invest, a term-based savings account might be a more straightforward option. One 95-day notice account offers up to 4.95 per cent annual interest, according to comparison site Raisin. Still, one-year gilts still offer a slightly more attractive return, currently yielding 5.1 per cent, excluding fees.

Rolls-Royce: high flyer

A mother’s response when a child declares they want to become a pilot when they grow up? You cannot do both.

Joking aside, maturity problems have plagued UK aero-engine maker Rolls-Royce for years. Chief executive Tufan Erginbilgic, in the job since the start of the year, promises to bring discipline. Wednesday’s profit upgrade sent shares higher by as much as 20 per cent.

Erginbilgic has been scathing in his diagnosis of Rolls-Royce’s problems. He claims it has suffered from decades of mismanagement and a culture unfit for a modern industrial leader. Profit margins from making and servicing jet engines are well below where they should be.

Favourable trends in aerospace markets are putting the wind under the wings of Erginbilgic’s turnaround. Rolls-Royce said that full-year underlying operating profits were now expected to be in the region of £1.2bn to £1.4bn. That is as much as two-fifths more than analysts had been expecting.

The boom in travel and tourism pushed up volumes for Rolls-Royce’s civil aviation division. Note that GE has just reported an almost 30 per cent increase in its aerospace revenues in the first half of the year.

More planes flying means more cash coming in. Rolls-Royce is also touting higher profits from cost savings and contract renegotiations. Unprofitable agreements were valued at £1.6bn at the end of 2022. More clarity on both profit drivers should be given at next week’s results.

Rolls-Royce shares have now doubled since the start of the year. The upgrade leaves them trading at 24 times this year’s earnings. But Rolls-Royce is barely making a low teens operating margin from its engines. Those of its peers are in their high teens.

A 16 per cent margin would add more than £700mn to operating profits for 2025, which translates into an 11 times price/earnings ratio. In the past decade, shares have only traded that cheap during crisis times. Market tailwinds and Erginbilgic’s adjustments both support the flight trajectory.

Lex is the FT’s concise daily investment column. Expert writers in four global financial centres provide informed, timely opinions on capital trends and big businesses. Click to explore

[ad_2]

Source link