[ad_1]

Receive free Emerging market investing updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Emerging market investing news every morning.

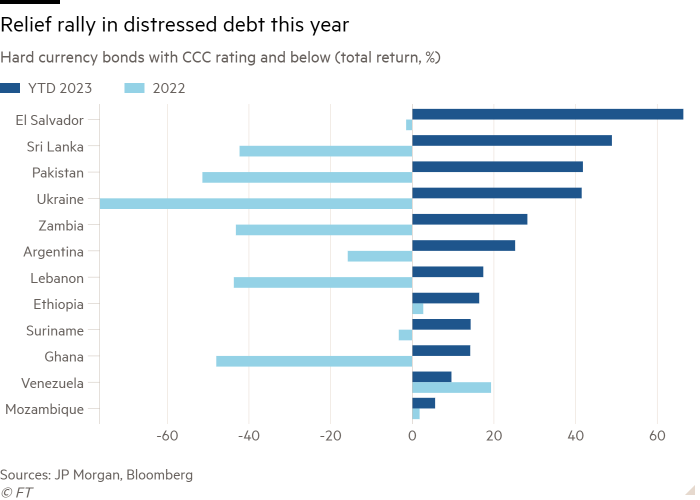

Bonds issued by some of the world’s poorest economies have been among the best performers in debt markets this year, helped by signs that global interest rates are close to peaking and breakthroughs in restructuring talks in countries pushed into default by the shocks of the past three years.

Sovereign bonds with rock bottom credit ratings of triple-C and below have delivered an average total return of 27 per cent since the start of the year, leading a rebound in foreign currency emerging market debt.

“Investors got absolutely crushed last year,” said Richard House, head of emerging markets in the fixed income team at Allianz Global Investors. “But they have done better this year and it’s partly because this distressed sector has performed spectacularly well.”

A rapid rise in global interest rates, soaring energy and food prices, a strong dollar and a global economic slowdown following the Covid-19 pandemic sparked a rapid sell off in “hard currency” — largely dollar-denominated — emerging market debt in 2022. This shut off most high yield economies from international financing, pushing countries such as Zambia and Sri Lanka into default and leaving many others on the brink.

But progress in those countries’ previously deadlocked restructuring talks has increased investors’ expectations of how much of their money they can expect to recover. Meanwhile, support from the IMF has helped stave off defaults elsewhere.

While a broad swath of emerging markets remains mired in debt distress, the resulting rally has brought a glimmer of hope to some countries — and bumper gains for bondholders.

“Without question we have had some good news from the IMF and tangible progress towards successful sovereign debt restructuring over recent months, from the likes of Sri Lanka, Suriname, Zambia and Pakistan,” said Paul Greer, emerging market debt and FX portfolio manager at Fidelity.

Greer said he had become more cautious of the distressed sector given the recent rally, but remains overweight some countries in default including Ukraine and Zambia, which both missed payments in 2022 and 2020 respectively.

Zambia had been in tortuous negotiations owing to a lack of agreement by China, the country’s largest creditor, and other western leaders over a proposal to reduce by about half the value of almost $13bn of external debts, but an agreement was finally reached last month.

Countries flirting with default have also experienced encouraging developments. Pakistan surprised markets by securing $3bn in short-term financing from the IMF late last month, offering the crisis-hit economy some reprieve.

“You came into this year with cash prices at the lowest level since 1998,” said Thys Louw, emerging market debt portfolio manager at investment company Ninety One. “People felt that as funding markets get shut off you’ll have a wave of defaults, but also the expectations for eventual recovery should you get to a restructuring were incredibly low,” owing to the Chinese involvement and a more combative IMF.

“A lot of the stories people were worried about have shown some signs of improvement,” Louw added.

Countries are generally considered to be in debt distress when the gap in borrowing costs rises to more than 10 percentage points above US Treasuries, making it prohibitively expensive for countries to raise external financing, increasing the likelihood of eventual default.

On that measure, 20 countries in JPMorgan’s emerging market sovereign bond market had fallen into debt distress by September last year, up from eight at the start of 2021. However, this year’s rally has seen the bond yield spreads of five countries fall out of distress, including Kenya and Nigeria, bringing them closer to the possibility of borrowing again on international markets.

“The prospect of market access that felt very very remote has increased a lot,” Thouw said. “It’s not that the good days are back, but that the good days may come again.”

Nigeria’s bonds have rallied by 6 per cent this year, as early moves by its new president put the country on a more orthodox economic trajectory. Bola Tinubu’s decision to scrap the fuel subsidies that cost Nigeria more than $10bn last year was viewed by investors as a key measure to help stave off default, alongside a decision to devalue the currency.

Kenya had been a big worry for markets with a $2bn bond maturing next summer, but its foreign currency debt has rallied since the IMF expanded its programme in May and it secured a $500mn syndicated medium-term loan facility earlier this month.

The sector has been helped by the long-dated maturities of its debt. Research by Morgan Stanley showed that 15 per cent of emerging market sovereign high yield debt will mature before the end of 2025, compared with 35 per cent for European high yield credit, and 59 per cent for Asian high yield.

But for countries that need to refinance maturing debt next year — including Egypt, Nigeria, Tunisia and Pakistan — the stakes are high. According to analysts at Bank of America, they need to deliver “very convincing reforms” in order to avoid making a potential default a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Credit rating agency Moody’s has downgraded the rating of 13 countries in JPMorgan’s EM sovereign bond index in the past 18 months, while only four have been upgraded.

“In general, we are still at a stage where we are seeing more downside than upside pressure” said Marie Diron, managing director for global sovereign risk at Moody’s.

[ad_2]

Source link