[ad_1]

Receive free JPMorgan Chase & Co updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest JPMorgan Chase & Co news every morning.

Thanks to their built-in transparency, there’s no shortage of information floating around about ETFs. But one of the most comprehensive regular industry snapshots is JPMorgan’s annual Global ETF Handbook.

The 19th edition — written by Marko Kolanovic and Bram Kaplan — landed a couple of weeks ago, and Alphaville has belatedly leafed through it for any interesting new titbits.

Most of it will be familiar to anyone with a passing knowledge of the ETF industry (there are some good explainers of basic ETF issues for those who need a catch-up). But as always, there is a lot of good data, pretty charts and interesting-ish observations.

Despite most markets chundering last year, the overall assets in ETFs globally has continued to climb: hitting $10.1tn at the end of May, up from $9.6tn a year ago. And there are now about 11,000 individual ETFs listed around the world, even if the US still dominates in numbers and volume.

Equity ETFs dominate, but bond ETFs have grown massively in recent years, and now accounts for about 21 per cent of the entire industry (ie about $2.1tn).

ETF options — and especially zero-day-to-expiry options on ETFs — have become hugely popular in recent years, and seem to have led to a massive decline in single-name options trading.

It’s hugely concentrated, however. JPMorgan notes that State Street’s S&P 500-tracking SPY, Invesco’s Nasdaq-linked QQQ and BlackRock’s small-caps IWM ETF account for about 94 per cent of all US ETF option trading volumes in 2023.

One thing that hasn’t changed is that fees keep coming down, and money mainly keeps gushing into the cheapest ETFs — trends that are two sides of the same coin.

JPMorgan estimates that the AUM-weighted average fee has halved in the US over the past decade to just 17 basis points today. Other markets lag behind, but the trend remains the same, across regions and asset classes.

Aside from the year ending May 2021 — when a bunch of pricier actively-managed ETFs were briefly red-hot (hello Cathie!) — funds in the lowest expense quintile attracted over 80 per cent of total flows across 2014-23.

That rose to 85 per cent last year, while the most expensive quintile only took in 4 per cent of overall flows.

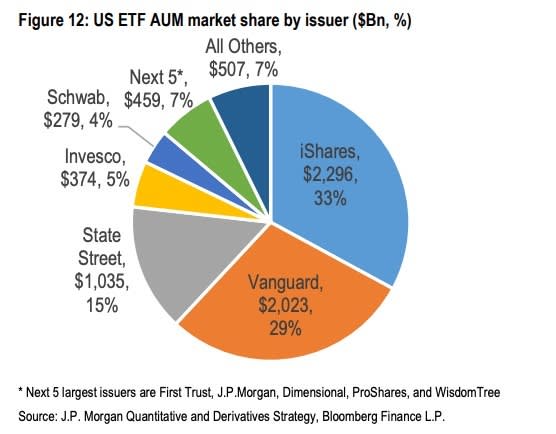

Another thing that didn’t change is that the Big Three — BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street — continued to be the Big Three, with their combined market share staying close to 80 per cent.

However, Vanguard’s market share of the ETF landscape continues to edge up, from 28 per cent in 2021 to 29 per cent this year. In trading volume terms, the popularity of State Street’s SPY (the most heavily-traded equity security on the planet) means it tops that table.

JPMorgan also seems to be notable adherents to the Age of the ETF thesis, with Marko and Bram predicting continued flows and more mutual fund-to-ETF conversions:

We expect ETFs to increasingly take market share of the actively managed universe from mutual funds, given ETFs’ advantages: typically lower expenses, greater tax efficiency due to in-kind creation/redemption and custom in-kind baskets for rebalancing, intraday liquidity and continuous pricing, and the ability to short and trade options. In the past couple of years, we noted how fund managers were beginning to convert some of their mutual fund offerings to the ETF wrapper. The past year, we have seen 16 such conversions, bringing the total number of mutual fund to ETF conversions to-date to ~40, with nearly $60Bn in assets. The largest conversion over the past year was the JPMorgan International Research Enhanced Equity ETF (ticker: JIRE), with $5.3Bn in assets. These successful conversions are likely to open the door to more fund managers following the same path in the future.

As such, we see strong growth potential for actively managed ETFs in the years ahead. However, the broader rotation from active to passive funds (which has seen over $3Tr flow in that direction in global equity funds over the past decade) appears unlikely to reverse near-term, suggesting the growth in active ETFs will likely come largely at the expense of active mutual funds rather than passive ETFs.

Elsewhere there are discussions of issues like the atrophying ETN market, the growing number of managed risk ETFs, single-stock ETFs, and Vanguard’s expiring ETF share class patent. You can find the full handbook here.

Further reading:

— The (American) age of ETFs

— Super passive goes ballistic; active is atrocious

— How passive are markets, actually?

[ad_2]

Source link