[ad_1]

Investors are having to adjust to the prospect of interest rates across major economies staying higher for longer than expected, after central banks warned the battle against inflation is still not yet won.

In a pivotal week in the monetary calendar, the US Federal Reserve surprised markets when it signalled support for two additional interest rate increases in 2023, even as it skipped a rise in June and kept its target range of between 5 per cent and 5.25 per cent. In the press conference following the meeting on Wednesday, chair Jay Powell said inflation “has not so far reacted much to our existing rate hikes, so we’re going to have to keep at it”.

The news prompted traders in Treasury futures markets, who have long been expecting the Fed to have to make cuts later this year, to remove those bets.

The European Central Bank announced the following day a widely anticipated 0.25 percentage point increase in rates, taking its deposit rate to 3.5 per cent. But ECB president Christine Lagarde delivered a more hawkish message than expected, stating that inflation in the eurozone is set to stay “too high for too long”.

Futures traders are now betting on the probability of two more rises instead of one, with major investment banks including Goldman Sachs and BNP Paribas expecting the benchmark deposit rate to reach 4 per cent by September.

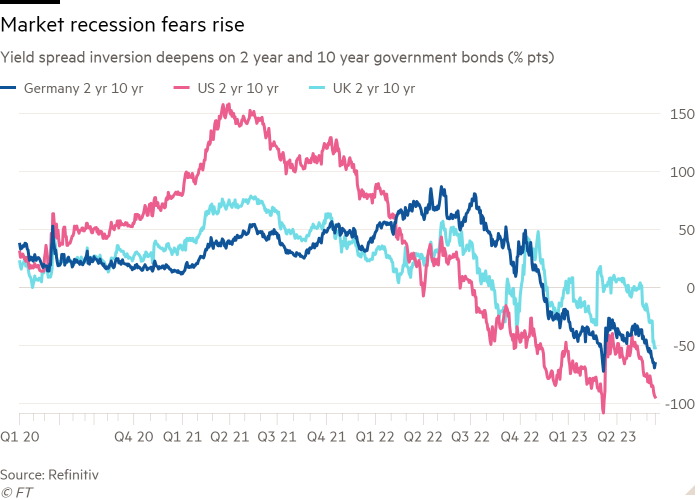

The shift has helped extend a months-long surge in short-dated bond yields, which closely follow interest rate expectations, in the US and Europe. Yields rise as prices fall.

Yields on two-year Treasuries, which tumbled in the wake of the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March, have surged more than a percentage point since early May, to 4.74 per cent. In the eurozone, yields on two-year Bunds have risen more than 0.8 percentage points since March, to 3.18 per cent.

Azad Zangana, a senior European economist at Schroders, said: “It’s pretty clear that rates have to be higher for longer, not only has demand turned out to be stronger than expected but supply issues push costs up — especially the shortage of workers in the labour market.”

The moves in the UK have been even more extreme, with yields on two-year gilts soaring more than 1.7 percentage points since March to above 4.9 per cent, with futures traders pricing in at least four more rate rises to a peak as high as 5.75 per cent.

“In the UK there is a real underlying inflation issue and it’s much more severe than in the euro area and the US,” said Christian Kopf, head of fixed income at Union Investment.

The upward moves in yields come after a number of fund managers had bet that central banks were close to the end of their rate tightening cycles and that yields were on their way down. A Bank of America survey of global fund managers this week showed they had an overweight allocation to bonds for six of the past seven months, having previously been underweight for 14 years.

Asset managers are holding the biggest long position in two-year Treasury futures — a bet on falling interest rates — since September 2019, according to CFTC data.

Mark Dowding, chief investment officer at RBC BlueBay, said he has moved to a “tactical long” position in US bonds, noting that “we are at a moment when the cycle is starting to turn and rates could look more attractive”.

He was sceptical the Fed will deliver two more rate rises, particularly if data comes in softer than expected, but added the central bank’s message was designed to quash the idea that it would quickly move to cut rates.

Expectations of higher rates come with mixed economic signals across the US and Europe. Investors are increasingly skittish about rates after unexpected pivots by the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Bank of Canada in recent weeks, both of which resumed raising rates after a pause, citing “upside risks” and “concern” about higher inflation, respectively.

The eurozone is in a technical recession, but Lagarde said the “incredible” strength of the labour market was the main reason for raising its forecast for core inflation to 5.1 per cent for this year, 3 per cent next year and 2.3 per cent in 2025. The core rate was 5.3 per cent in May.

Dario Messi, a fixed-income analyst at Julius Baer, said: “It will be difficult to justify a tightening pause as long as the inflation forecast on the longer-term horizon does not converge towards the 2 per cent target.”

This has increased nerves that central banks will be unable to bring down inflation without triggering deep recessions, particularly in Europe.

The rally in short-dated bond yields this week has not been matched by yields on longer-dated peers, with 10-year bonds trading well below the rate on two-year securities, bringing the depth of the inversion — a closely watched recession indicator — near to levels seen in the spring, when banking crisis fears sparked panic across global markets.

“The market will have to account for the increasing probability that this narrow focus on current inflation to determine the ECB’s success results in a policy error further down the road,” wrote analysts at ING. “Hence the reluctance in longer rates to follow the front end higher”.

[ad_2]

Source link