[ad_1]

Wall Street is slowly revving back up its junk debt machine.

Banks have agreed to lend billions of dollars to finance leveraged buyouts by Apollo Global, Elliott Management, Blackstone and Veritas Capital in recent months, as Wall Street re-enters a market that left it nursing painful losses over the past year.

It is welcome news for the private equity behemoths who are sitting on hundreds of billions of dollars of dry powder and searching for attractive financing options, as higher interest rates eat into their returns.

Bankers say that, despite the turmoil that hit the banking sector this spring, underwriting is becoming a more attractive option once again.

“Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse hit just when we were catching a bid, slowing us down,” said Chris Blum, the head of corporate finance at BNP Paribas. “[But] you’re starting to see the syndicated option come back.”

Investment banks’ revenues have been hard hit by a sharp drop in corporate and private equity dealmaking, with a darkening economic outlook and the banking crisis in the spring helping push mergers and acquisitions volumes to their lowest level in a decade in the first quarter.

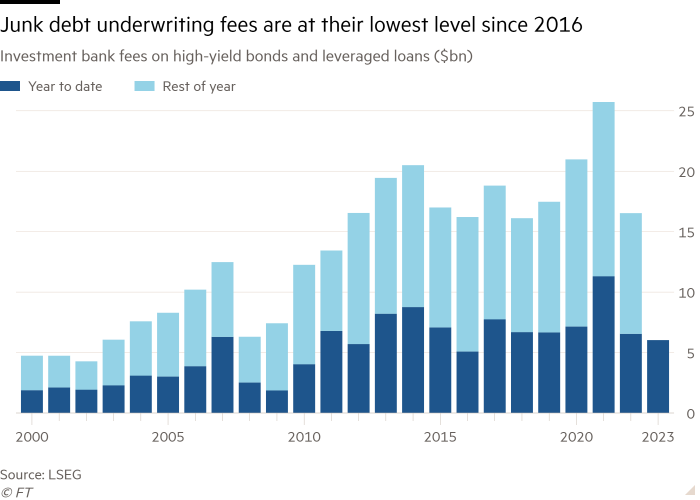

Fees underwriting junk bonds and leveraged loans — the debt used to cobble together leveraged buyouts — are down more than 20 per cent from the five-year average, according to data from the London Stock Exchange Group.

Banks now hope to take advantage of a rally in junk bond and leveraged loan markets this year, which have been starved of new issuance. Private equity firms had largely turned to direct lenders such as Apollo, Blackstone Credit and HPS Investment Management to fund their takeovers as public markets whipsawed in value and banks grew reluctant to lend.

“As lenders, we have been telling banks, ‘We are open for business, you can syndicate into our market’,” said Lauren Basmadjian, co-head of liquid credit at Carlyle, who invests in syndicated loans, although she added that some banks were “still reluctant to underwrite”.

“We may see the pendulum swing back and forth the entire year when our market looks good to access,” she said.

This month, a group of banks led by Goldman Sachs agreed to lend $3.7bn to Elliott and some of the firm’s partners backing the takeover of healthcare company Syneos. The bank financing package beat a rival proposal from private lenders, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

That comes on the heels of Blackstone’s decision to swap a debt package that included $2.6bn of private loans — loans from non-bank lenders that don’t trade on public markets — that it had lined up for an investment in the climate technology unit of Emerson to public markets. It was a setback for the private lenders, including Sixth Street, Goldman Sachs Asset Management and Apollo, given they had to have the cash ready to go for the loan had Blackstone completed the deal as initially planned.

The private lenders were paid a break fee after losing the deal, which was ultimately funded with $5.5bn of debt, including a $2.7bn term loan at far more favourable rates, sources noted.

Apollo’s takeover of Arconic, announced this month, is also set to be financed by banks including JPMorgan before the loan is sold to other investors.

Marc Lipschultz, co-chief executive of asset manager Blue Owl, said the banks had taken a “rifle shot” approach when agreeing to fund private equity buyouts, meaning they were being very selective.

Banks have predominantly stepped in on deals when the amount of debt and the credit risk was relatively low, at least by private equity industry standards. That was the case on two recent deals banks have financed: Silver Lake’s $12.5bn purchase of Qualtrics and Blackstone’s $4.6bn takeover of event software company Cvent.

Public market deals hold big benefits for private equity groups: the interest costs are often lower and they can often get far more favourable covenants compared with private debt. But, unlike private credit, the deals include a mechanism that allows banks to raise a company’s borrowing costs if market conditions change. Private credit funds also market themselves as being able to execute deals quicker.

The bank exodus from underwriting new debt followed the market sell-off last year, sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and persistent inflation. As the Federal Reserve rapidly increased interest rates, nearly every Wall Street institution, including Bank of America, Barclays and Morgan Stanley, suffered losses on loans that they had agreed to provide to their private equity clients before markets plunged in value.

The backlog of those deals, including the $13bn loan that financed Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter, prompted many lenders to stop agreeing to risky new loans altogether. Banks lost about $1.5bn underwriting a debt package funding Elliott’s and Vista Equity Partners’ $16.5bn buyout of Citrix.

For riskier deals, private credit remains the go-to. Among the companies in talks with private credit funds is Finastra, a financial technology business owned by Vista Equity Partners. The company’s triple C plus credit rating is one of the lowest assigned by the big rating agencies, with analysts at S&P Global warning its upcoming debt maturities “present significant refinancing risk”.

Private credit funds have stepped in and are offering to provide $6bn of loans, split across senior and junior tranches, according to people involved in the situation.

Advent and Warburg Pincus have also turned to private credit managers for a nearly $2bn loan to fund their purchase of a division of healthcare company Baxter International.

“We are seeing the banks consider new underwrites for existing issuers and conservative structures, but there are still large swaths of the market that are the domain of private credit,” said Michael Zawadzki, chief investment officer of Blackstone Credit.

Additional reporting by Antoine Gara

[ad_2]

Source link