[ad_1]

The energy may be renewable. That does not always seem to apply to investor enthusiasm. Green energy stocks have swung from high to low like the tip of a wind turbine blade. Even so, they play a growing role in the portfolios of private investors.

But what is the best way to participate? Through “pure green” energy groups? Or via businesses that are themselves in the process of transformation?

Two years ago investor enthusiasm for companies pursuing climate-friendly policies reached feverish levels. The problem was that too much capital chasing too few big businesses pushed shares too high. Stocks such as Denmark’s Orsted tumbled when their energy output was disappointing.

Orsted sold its oil and gas operations years ago to become the world’s largest wind farm operator. Its shares now trade at what green investors would see as a depressed level. Shares are worth 13 times estimated cash profits, defined as earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation.

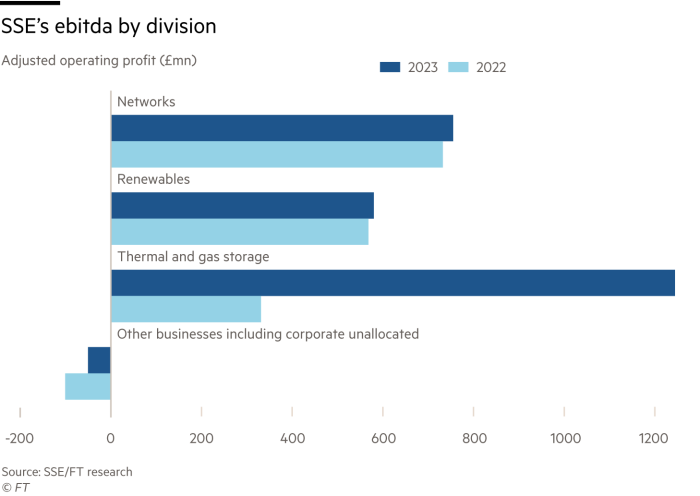

The stock of UK energy group SSE is even cheaper at nine times forecast ebitda. This is because it is exposed to the old energy economy as well as the new one. The FTSE 100 company builds and operates renewable energy infrastructure such as offshore wind farms in the UK. It also owns electricity grids in Britain. Its thermal business runs gas-fired power plants and methane storage facilities.

A pure-play renewables group such as Orsted is easy to understand at an operational and ethical level. But its shares — and accordingly its cost of capital — are likely to be volatile. A mixed energy company such as SSE is more opaque but is also a steadier proposition. It can finance its green expansion internally using cash flow from “dirty” hydrocarbon-related businesses.

SSE resisted pressure from US activist Elliott to spin off its renewables arm in hopes of a value pop. Longstanding boss Alistair Phillips-Davies can now feel justifiably smug for holding out.

SSE’s diversified structure helped it during 2022 as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shook up energy markets, its full-year results this week showed.

Its thermal generation business contributed most to adjusted annual pre-tax profits, up 89 per cent to £2.2bn. Gas-fired power plants help to meet electricity demand in Britain when renewables such as wind and solar units cannot.

Despite the country growing its share of wind and solar assets, gas-fired power stations remain the single biggest power source. Last year they accounted for 38.5 per cent of Britain’s electricity generation mix.

Profits growth at SSE’s renewables business was ironically damped by insufficiently blustery weather conditions last year. A UK windfall tax on low carbon electricity generators cost it £43mn. Less diverse companies such as Orsted have recently fared poorly.

SSE wants to expand all three of its units. It upgraded investment plans to spend £18bn by 2026-27, half of which will go towards networks. Previously SSE had targeted £12.5bn of investment by 2025-26. Last year’s strong performance also means SSE will no longer have to sell a stake in its electricity distribution network business — which takes electricity from the national grid and transmits it to homes and businesses — to fund its investments.

Not everything has gone well. SSE must cope with rising supply chain costs. Wind turbine makers have increased their average selling prices by more than 33 per cent since the end of 2021 to offset rises in input costs for steel and copper. Indeed, £2bn of SSE’s upgrade to its investment plan accounts for supply chain cost increases. New energy projects in the UK are also facing lengthy hold-ups in securing grid connections.

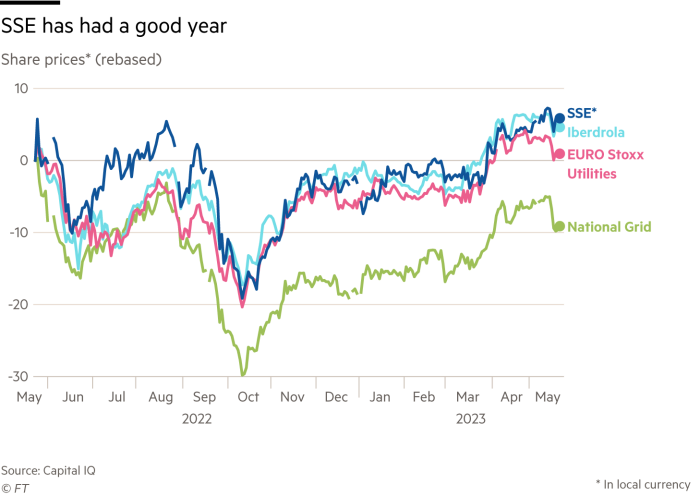

The shares have fared well so far this year, rising 12 per cent. Its shares trade on a forward earnings multiple of more than 12.5 times, cheaper than some European peers such as Iberdrola on 16 times, as well as National Grid at 15.7 times. The chill wind of break-up calls could return. But for now SSE has done enough to silence its critics.

Drahi dials up more shares in BT

SSE might be out of the eye of the storm. But there is interference on the line at another UK company, BT.

The Israeli tycoon Patrick Drahi — owner of auction house Sotheby’s — has increased his holding in BT to 24.5 per cent. A 30 per cent mandatory bid trigger — according to the UK’s Takeover Panel — is hoving into view.

But Drahi’s holding company Altice could not easily acquire BT. Has the wheeler dealer — who favours using debt for acquisitions — mellowed into a middle-aged rentier, content to collect the UK telecoms group’s 5 per cent annual dividend yield?

Altice argues that BT offers long-term value. It says it has no plans to bid for BT — with some significant exceptions. These include a board recommendation or a third-party offer.

UK officials approved an increase in Drahi’s shareholding to 18 per cent. His interest is now hovering at just under the 25 per cent threshold that would trigger another review. The UK would probably block the full purchase of BT by a debt-heavy foreign buyer, even if BT directors agreed and Drahi could finance the deal. The UK would hardly be keener on Drahi buying BT’s broadband unit Openreach.

Altice says Openreach’s fibre buildout is what attracts Drahi to BT Group. That makes up more than half of BT Group’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation, giving it a possible value of over £20bn.

With 37,000 employees, plenty of whom are part of the BT pension scheme, Openreach looks doubly difficult to prise away. BT only expects its pension scheme — which has a £3.1bn deficit — to be fully funded by 2034. Trustees there have influence and can demand deficit reduction in the event of a takeover. That would raise the cost of buying any part of BT.

Drahi’s shareholding amounts to a blocking stake. But it is hard to see how he could sell it without a viable alternative bid. It mostly consists of cash equities, some acquired during hectic trading after BT presented mixed full-year results last week.

Add Drahi’s stake to the holding in BT of Germany’s Deutsche Telekom and you get to a 37 per cent overhang, New Street Research notes. Neither side can easily sell to the other.

In philosophy, Occam’s razor insists the simplest solution is most often right. That would mean Drahi simply expects BT to roll out fibre rapidly and profitably, boosting its share price.

The tantalising possibility remains that he has a side bet on mergers and acquisitions activity that changing circumstances could activate.

Lex is the FT’s concise daily investment column. Expert writers in four global financial centres provide informed, timely opinions on capital trends and big businesses. Click to explore

[ad_2]

Source link