[ad_1]

Investors have only so much control over the gross returns their portfolios realize. Even when constructed well, a portfolio’s performance is mostly subject to the whims of the market. But investors do have some degree of control over their net returns: by limiting the fees they pay their investment managers and what they have to send to Uncle Sam.

One of the tools at an investor’s disposal for enhancing the tax efficiency of their portfolio, and limiting their tax liability, is tax-loss harvesting (TLH). Tax-loss harvesting is a strategy that entails selling one asset to realize a capital loss in order to offset current or future-year capital gains created from the selling of another asset.

By helping to defer the realization of capital gains, TLH enables enhanced compounding of investment returns until tax liabilities are eventually paid. Sometimes, a tax liability incurred can be eliminated in its entirety by taking advantage of the step-up in cost basis when an asset owner passes away and transfers their estate.

Example of TLH Benefits

The following example helps demonstrate how TLH can assist in deferring taxes. Imagine two investors who are identical in every respect, both individuals invested two million dollars and both investments doubled to four million dollars over ten years. The only difference is that one investor utilized tax-loss harvesting while the “traditional” investor did not.

Next let’s imagine that each investor partially liquidates their portfolio to generate $200k in cash. For simplicity, we assume each investor is subject to an all-in 25% marginal capital gains tax rate.

Because of this 25% tax rate, the traditional investor must sell $228,571 of their holdings to raise $200k net of taxes. In so doing, they realize $114,286 in capital gains and pay $28,571 in taxes. They’re left with their desired $200k in cash flow from the investment sale, and they now have $3.771m in stock with a cost basis of $1.886m.

Consider the investor who has been tax-loss harvesting over the ten-year investment span. The calculations are a little more complex. Let’s say their tax-loss harvesting activity realized $800k in losses over the decade, resetting their cost basis from $2.0 million down to $1.2 million.

These realized losses carry forward from one year to the next and are available to offset some or all capital gains realizations, depending on the size of a stock sale. This investor sells $200k of stock with a cost basis of $60k.

Thus, this sale realized $140k of capital gains. But this $140k capital gain is more than offset by the $800k in existing carry-forward losses. No taxes are owed, and the carry-forward loss shrinks to $660k.

The TLH investor now owns $3.800m in stock with a $1.114m cost basis. If their investment value is unchanged, they can sell an additional $943k in stock before exhausting their carry-forward losses. Despite having investments that have doubled in value, TLH enables this investor to liquidate over $1.1m of their holdings before generating any tax liability.

Depending on their lifetime liquidity needs, it’s possible that this investor may pay little, or no, capital gains taxes, and their heirs can enjoy a full reset of the remaining stocks’ cost basis at their time of passing.

I’ll offer a quick caveat that the benefits of deferred capital gains realizations are not universal. For those who might temporarily find themselves in low marginal tax brackets, the strategic realization of capital gains could be sensible.

For now, let’s focus our attention on high-net-worth investors who do not benefit from low marginal tax brackets. For these investors, achieving a higher TLH yield is generally beneficial.

Enhanced TLH Yield Potential When Buying Individual Stocks

Does the structure of an investor’s portfolio materially impact the efficiency of a TLH program? Seeking to answer this question, I recently co-authored a paper with Jason Lu that horseraces automated TLH when buying a broad-based equity index ETF against buying a direct indexed portfolio of individual stocks. The paper demonstrates a material potential benefit to owning individual stocks: higher average TLH with more consistent tax-loss harvesting performance.

A portfolio of individual stocks typically offers many more opportunities to realize losses than an ETF that holds the same positions. This might be most easily demonstrated by constructing a simple index that owns two stocks. Imagine two stocks, ticker symbols WIN and LOSE, which are each initially priced at $50. The index owns one share of each and has an initial value of $100. The price of WIN increases to $70 and the price of LOSE declines to $40. The index value has climbed to $110.

Someone who owns the index ETF has no opportunity to harvest a loss as their investment value has increased by 10%. But, someone who instead owns one share of WIN and one share of LOSE can harvest a loss. They sell their share of LOSE for $40, realizing a $10 loss (10% of their total initial investment). They reinvest the proceeds in a stock that serves as a substitute for LOSE.

Both the stock investor and the index investor have a portfolio that has grown in value from $100 to $110, a 10% gain, but the index investor has a cost basis of $100, an unrealized $10 capital gain, and $0 in realized capital gains/losses.

The stock investor, on the other hand, has an updated cost basis of $90, an unrealized $20 capital gain, and $10 in realized capital losses. By owning the underlying positions, the stock investor has been able to harvest a loss that is simply unavailable to the index (ETF) investor.

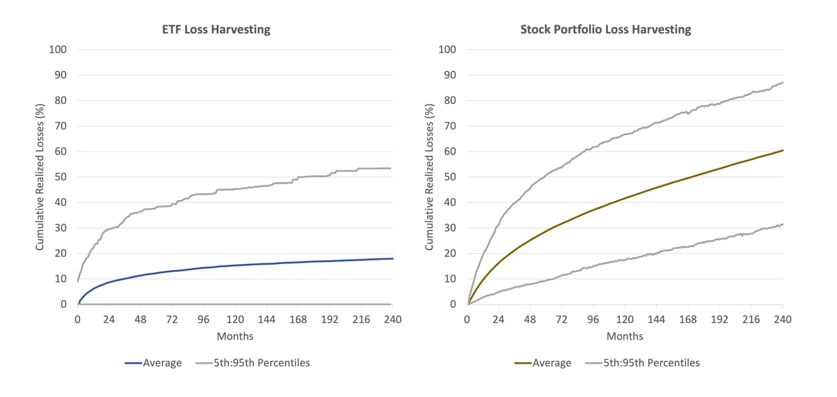

The impact of this difference in investment structure on TLH yield is material. The following figure (Figure 5 from the paper) shows the extent of the advantage we measured. Over a twenty-year period:

- The stock portfolio harvested about triple the losses of the ETF;

- The worst 5% of outcomes for the stock portfolio had about a 50% higher TLH yield than the average TLH when owning ETFs; and

- The average TLH yield for stocks was higher than the best 5% outcome for ETFs.

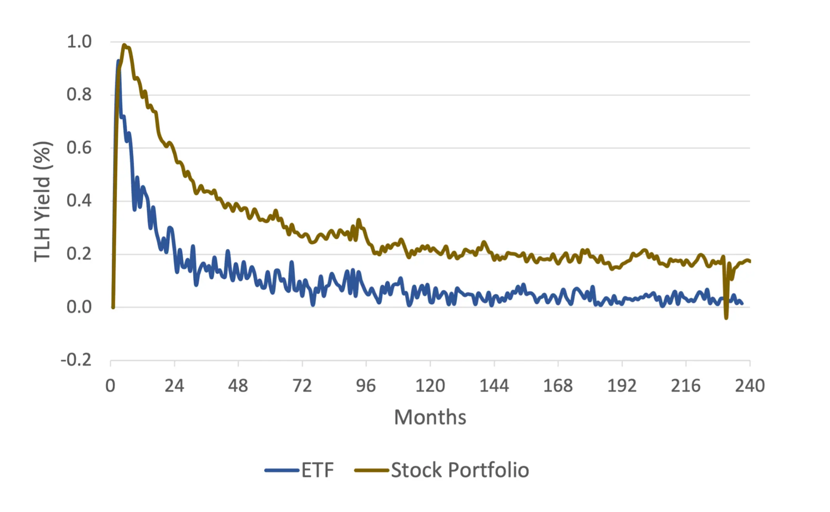

Loss harvesting benefits are front-loaded, but then exhaust over time. Our paper demonstrates this effect when harvesting losses on ETFs or on a portfolio of direct stocks (Figure 6 from the paper). However, a few interesting findings emerge:

- The initial harvesting yield for ETFs and individual stocks were nearly comparable;

- TLH yield decayed significantly quicker for ETFs than for individual stocks;

- After about five years, TLH yield for ETFs was barely above zero; and

- TLH opportunities – albeit modest – continued to materialize for a portfolio of individual stocks over an extended time frame.

Tax-loss harvesting can be an effective tool for improving the tax efficiency of a portfolio. It may be used to bank realized losses that can be carried forward to offset future capital gains. Doing so can defer the realization of tax liabilities, and in some instances when coupled with the step-up in cost basis at death, can eliminate them altogether.

However, the structure of a portfolio plays an important role in the productivity of a TLH algorithm. Owning individual stocks typically presents more opportunities to harvest larger losses. Even a naïve harvesting algorithm applied to a portfolio of stocks is likely to best a sophisticated harvesting algorithm applied to ETFs.

There are many considerations at play when an investor chooses whether to own stocks or ETFs. For the tax efficiency arising from TLH, and the ability to hold onto more of your own money, our research shows that owning individual stocks easily wins the horse race.

Roni Israelov is Chief Investment Officer and President at NDVR.

[ad_2]

Source link