[ad_1]

Happiness levels have failed to return to their pre-pandemic norm in the UK, particularly among younger people as the blow of Covid-19 on the nation’s mental health is compounded by the cost of living crisis.

Twenty-three per cent of Britons reported their life satisfaction was “very high” in the last quarter of 2022, down from an average of 30 per cent in 2019 before the health crisis, according to new data from the Office for National Statistics.

The proportion dropped to 19 per cent for people in their 20s, well below the 32 per cent for those aged 60 and over, the data showed.

The figures also indicated that the share of those reporting high levels of happiness was below 30 per cent, down from an average of 35 per cent in 2019. In contrast, anxiety is up from pre-pandemic levels.

Andy Bell, chief executive of the Centre for Mental Health charity, said that “mental wellbeing in the UK is deteriorating as the cost of living crisis continues to bite”.

He added: “As more people struggle financially, the risks to our mental health grow and more people find themselves experiencing low wellbeing.”

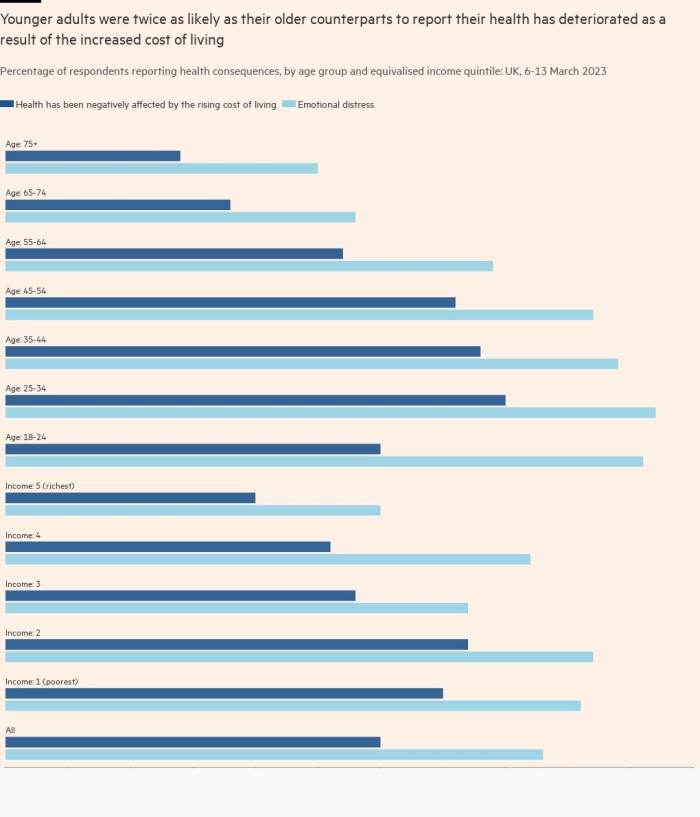

The official figures chime with a large study by the Resolution Foundation think-tank, conducted in March which found that 30 per cent of respondents — or 16mn adults — said their health had been negatively affected by rising living costs.

The proportion rose to two in five for people aged 25 to 34.

In March, UK inflation was at 10.1 per cent, while food inflation reached a 45-year high of nearly 20 per cent. Meanwhile, mortgage payments rose to the highest share of income since the 2008 financial crisis.

Simon Coombs, founder director of Working Minds Group, a provider of wellbeing support, said that food, water and shelter, key components for feeling secure, are all “currently under threat”.

The average waiting time for mental health support on the NHS is now between six and nine months in most areas of the UK, Coombs noted, as the service struggles to cope with the combination of a jump in demand and long-term underfunding.

Alexa Knight, director of England at the Mental Health Foundation, said that concerns about finances were reducing people’s ability to get good quality sleep, exercise and spend time with friends and family, causing a “mental health emergency”.

Inflation and borrowing costs have surged in the wake of the coronavirus crisis which itself took a heavy toll on people’s mental health.

Brian Dow, deputy chief executive of Mental Health UK, said the “cost of living has hampered the nation’s recovery from the pandemic, people’s wellbeing has clearly continued to suffer”.

[ad_2]

Source link