[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. It’s Jenn Hughes here in New York, standing in while Rob and Ethan are away. Wall Street has plenty to digest this week, with crucial inflation data and the start of an earnings season that’s likely to show emerging economic cracks. Can poor profits and a weakening outlook topple the Fed as the guiding markets narrative? Next up on Unhedged will be Treasuries market maven Kate Duguid on Thursday. In the meantime, email me: jennifer.hughes@ft.com

The Good, the Bad and the Earnings forecasts

It’s been four weeks since markets swooned following the failure of two US banks in three days. Silicon Valley Bank folded on Friday March 10, then investors were further rattled by regulators’ takeover of New York-based Signature Bank on the Sunday.

Looking back, the most remarkable thing is how well stocks have held up. They’ve done this in the case of the S&P 500 by shunning a few affected players (First Republic Bank, down 83 per cent) while bidding up mega-caps such as Microsoft, up 16 per cent.

Banks generally have suffered, although it says a lot about regulators’ swift action on March 12 that the losses of smaller lenders — measured by State Street’s SPDR regional banks ETF, down 15 per cent — aren’t markedly worse than the biggest players represented by the KBW index, which is off 12 per cent.

More telling still is the small-cap Russell 2000, which is dead flat despite the fact that its constituents are more likely than their big peers to be hurt by nervous banks pulling back. Earnings estimates for S&P 500 stocks have fallen 4 per cent this year — and slipped 1 per cent since the banking turmoil — but Russell 2000 earnings forecasts are down 11 per cent and 4 per cent, respectively, according to Goldman Sachs.

And banks certainly are pulling back. The Dallas Federal Reserve last week published its latest banking conditions survey (h/t Apollo’s Torsten Slok), conducted after the collapse of SVB and Signature Bank, and which was bluntly titled “Loan demand falls and outlooks worsen”.

The surveys are conducted twice each quarter. What’s particularly noticeable is how the previous one in mid-February showed improvement in lending volumes. That just makes the swing lower last month all the more stark.

One more note of caution. In addition to whether companies meet their first-quarter earnings forecast, it’s also worth considering how they’ve splashed (or not) the cash. Buybacks were last year’s casualty, as per this chart from Goldman Sachs analysts. Signs of cutbacks to future investments, such as research and development or capital expenditure, would be far more worrying — and add to the argument that this economic downturn is more serious than the stock market currently thinks.

Is bank research worth paying for?

I reported yesterday on US banks getting entangled in extra regulations courtesy of Europe’s Mifid reforms, which forced investors to split payments for bank research from sales and trading.

Beyond the technicalities (story here), there lies the long-running issue in how fund managers should pay banks for research — and where its value lies.

Critics of the 2018 painfully named Markets In Financial Instruments Directive II say that it has resulted in plummeting payments for research in Europe, sharply reduced analyst headcount and shrinking liquidity for swaths of small and mid-cap stocks without analyst coverage to pique investor interest.

But is it really so awful? Asking for friends in US asset management, several of whom would like to shop for trading services separately from picking their preferred analysts.

Life (and this newsletter) is too short to digest in full the growing pile of research on Mifid II’s impact. So here are a few points with the aim of sparking discussion.

-

Mifid-affected asset managers certainly cut their research budgets. Payments dropped up to 30 per cent, according to the British, and more than halved, per French figures.

-

Still, a 2021 paper in the Journal of Financial Economics found that analysts who remained “produce better research, and . . . analysts who produce worse research are more likely to leave the market”. That doesn’t sound like the worst outcome.

-

The UK regulator in 2019 “found no evidence of a material reduction in research coverage, including for listed small and medium enterprises”.

-

It’s not just the UK, which after all first proposed the research/trading split, but a 2021 working paper from the European markets regulator also said “the quantity of research per SME has not declined relative to larger firms”.

-

A 2022 study by the US Securities and Exchange Commission found that the effect of Mifid on coverage of smaller companies was “inconclusive, unclear, or difficult to isolate”.

-

Intriguingly, Howell Jackson at Harvard Law School and Tyler Gellasch of the investor-backed Healthy Markets Association reckon the initial US OK for bundled commissions in 1975 was only meant to be temporary

-

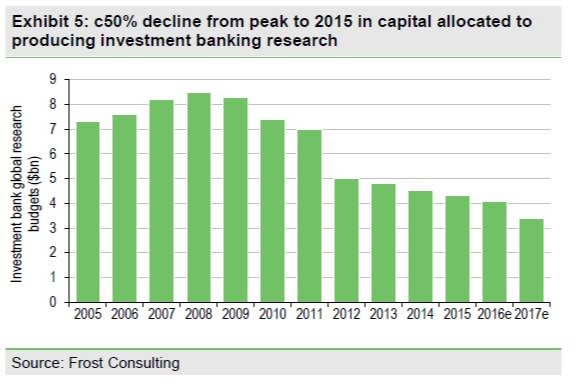

It’s hard to pin all the blame for dwindling analyst numbers on Mifid II when a 2016 consultants’ paper reckoned the average number covering stocks globally had halved between 2007 and 2012. Fast-falling bank budgets, as per this chart, can’t have helped either.

There’s no doubt Mifid II has caused pain and cost jobs. Brussels officials thought asset managers would pass the costs on, not bear them as most did. That’s added to the general parsimony over payments.

Some degree of “rebundling” of research and trading for smaller companies is being discussed in Brussels and also London, which is desperately seeking ways of boosting lacklustre post-Brexit capital markets. Providing more analyst coverage could certainly help — but at whose cost?

There seems to be a danger here of confusing the problem of a lack of attention paid to smaller companies with a quantifiable service offered by investment banks — a group not known for prioritising the wider financial ecosystem over its own wellbeing. Is getting investors to pick up the tab via bundled services really the best solution?

Answers in an email, please.

One good read

On the significance of President Joe Biden’s visit to Northern Ireland, Jonathan Powell, the writer and a former British government negotiator, points out just how few successful peace deals there have been in recent decades.

Recommended newsletters for you

[ad_2]

Source link